: The Stevenson family tamed Scotland’s wild coastline with their lighthouse. A new online resource showcases their remarkable achievements, reports Sandra Dick.

For those in peril on the seas or simply trying to find their way home, the reassuring glow from the lighthouses they built offered a welcome beacon of hope in the dark, stormy night.

And for those attempting to navigate Scotland by pony and trap, on horseback or hardy souls on foot, the bridges they designed offered a welcome solution to painful journeys that might otherwise have involved extra miles and even days of exhausting travel.

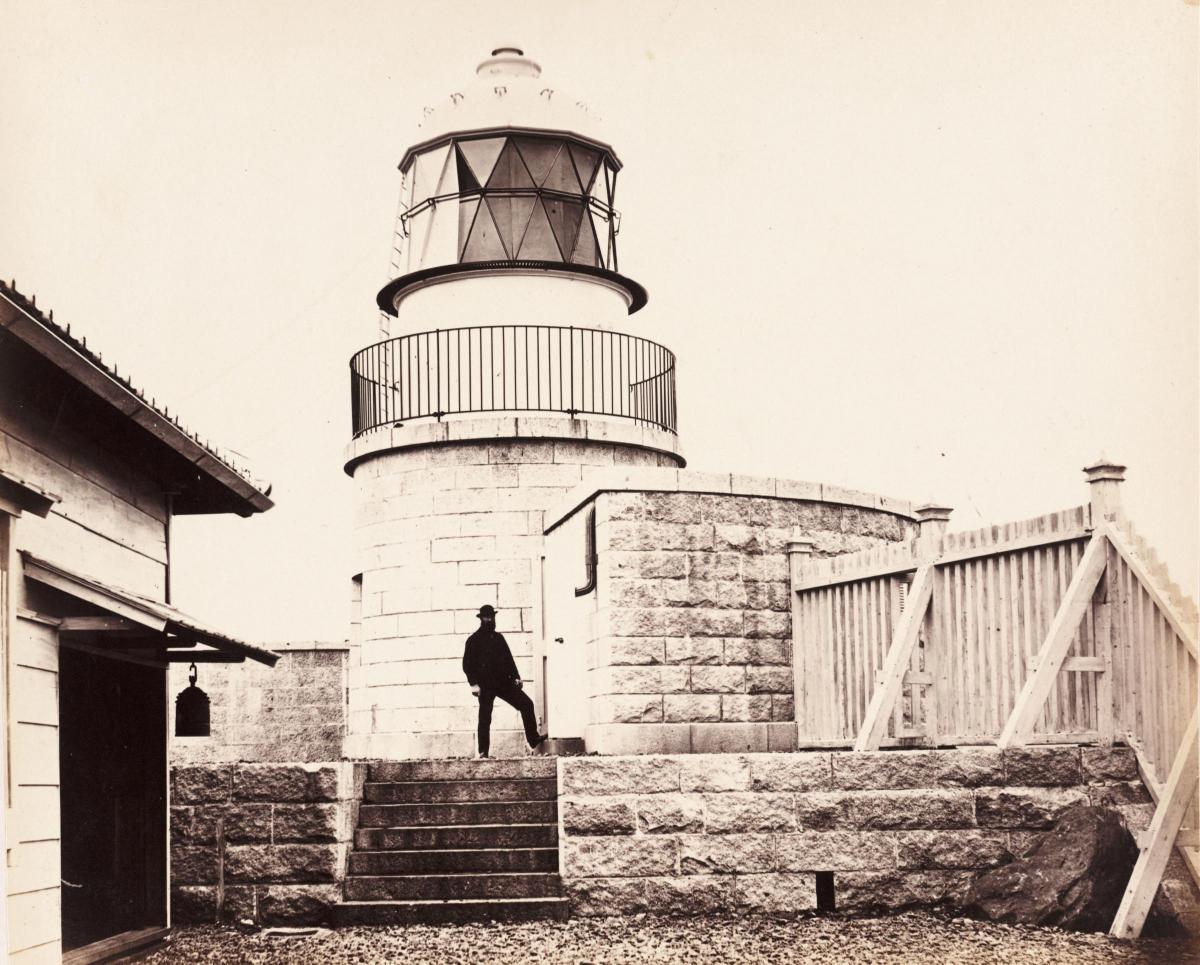

Across the length and breadth of the country, harbours, crossings, canals, river improvement works and, of course, scores of lighthouses rooted on rocky outcrops that have sent their warning light into the darkness for more than 150 years, are stamped with the name of a single pioneering engineering family.

While one son, Robert Louis Stevenson, would spurn engineering to achieve fame for his literary achievements, other members of the Stevenson family were busy taming Scotland’s wild coastline, building towering lighthouses that defied the elements.

Many, even in this digital age of modern navigation equipment, still shine on through the harshest stormy night, albeit operated by remote control from the heart of Edinburgh.

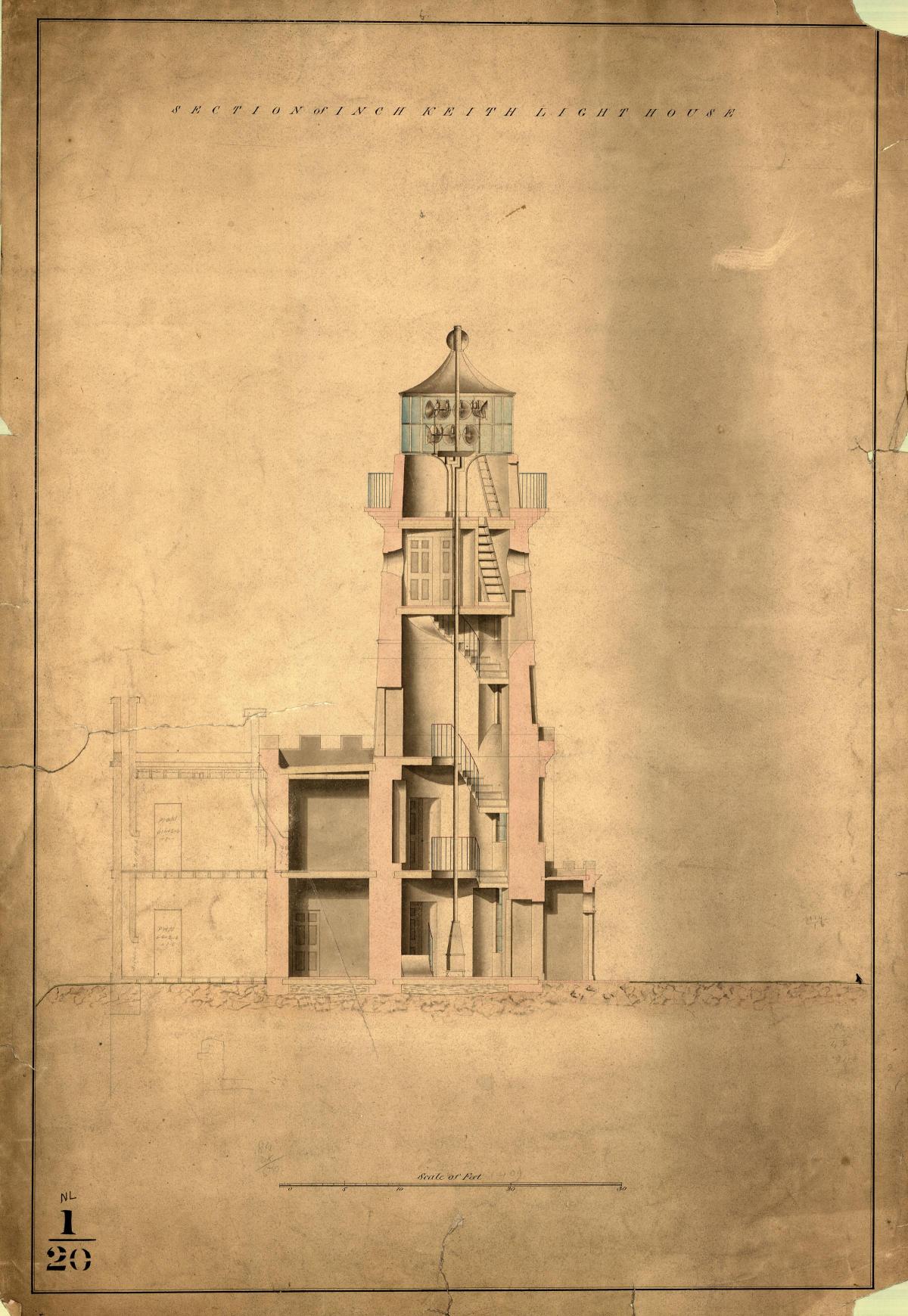

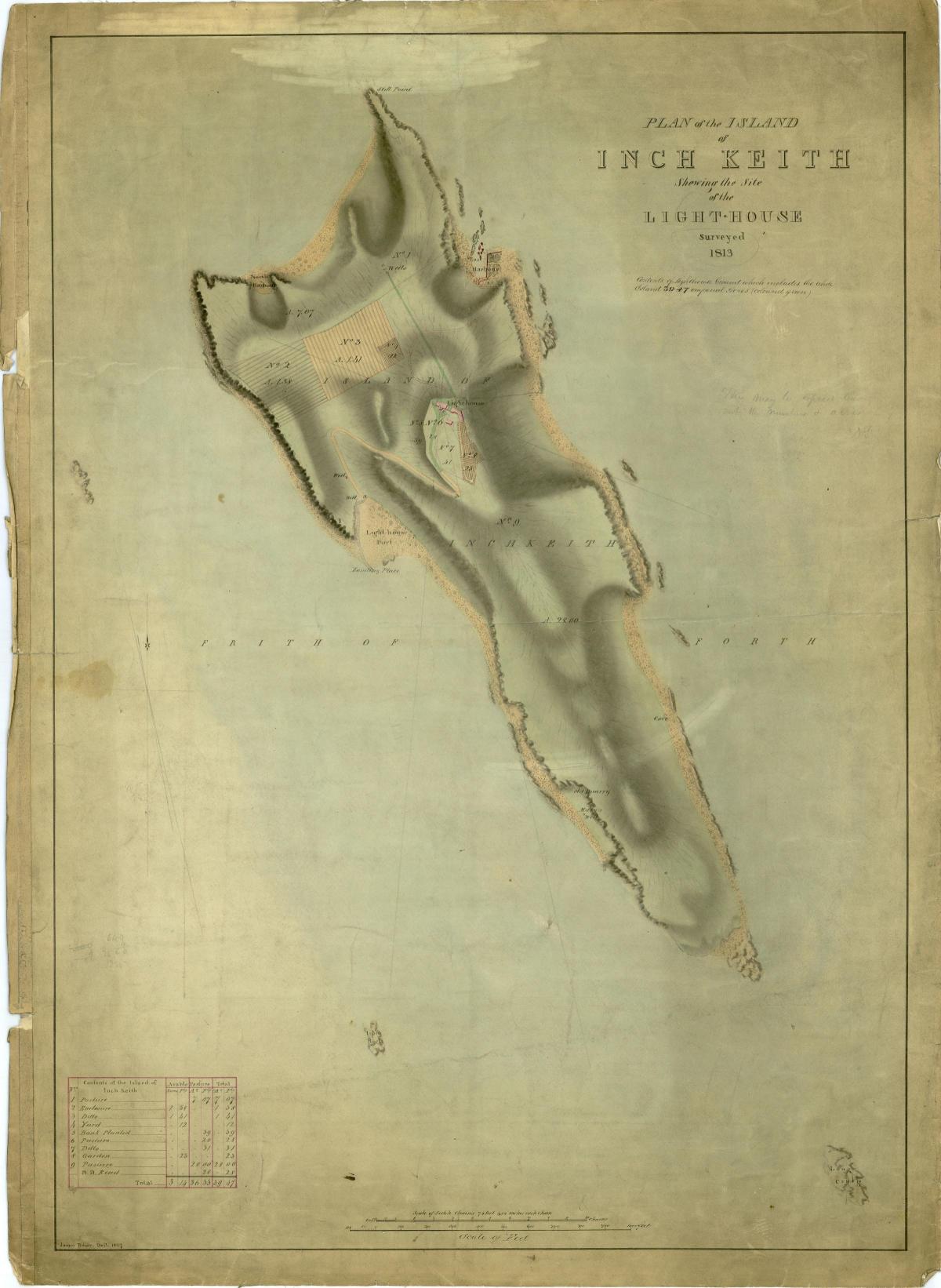

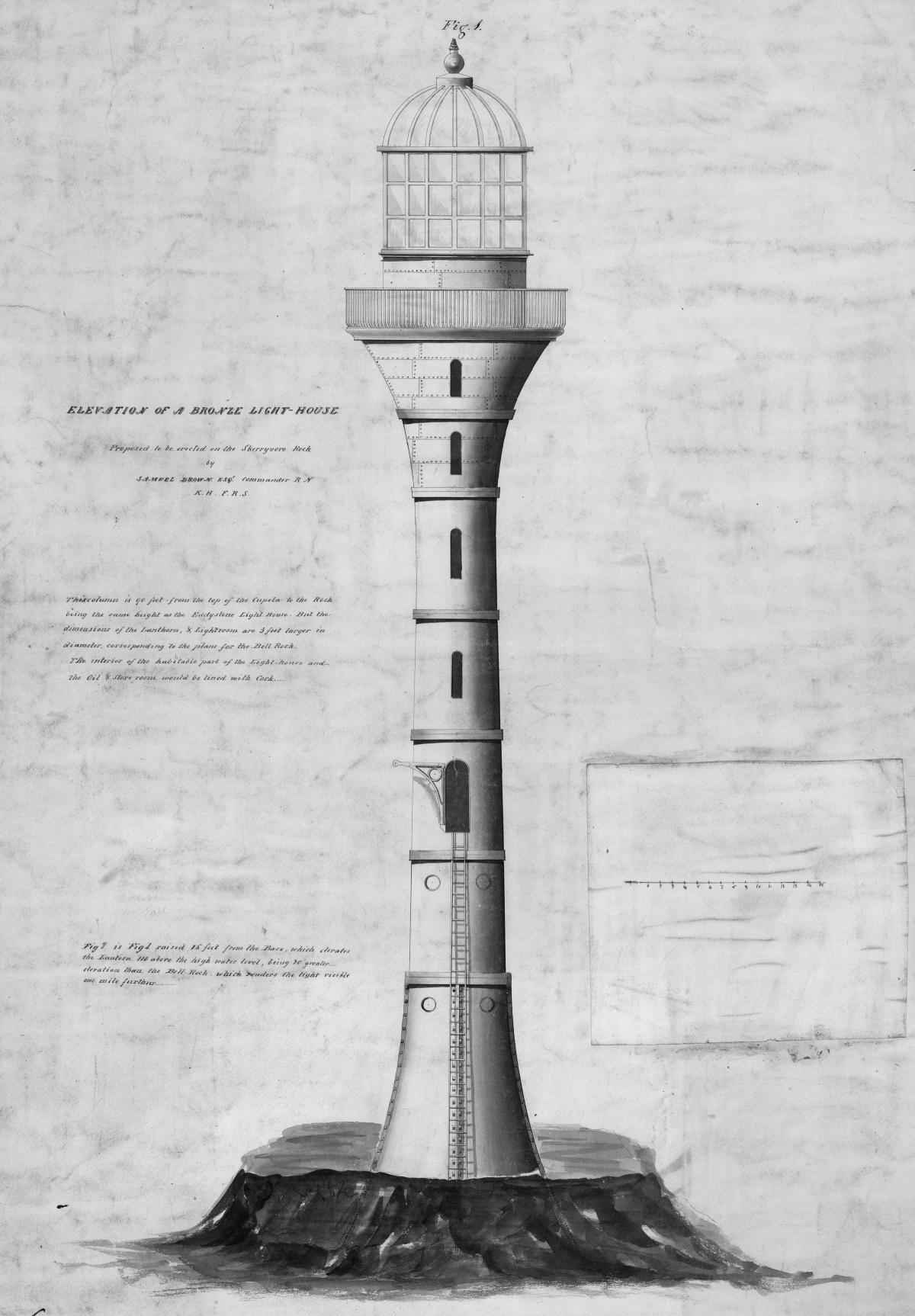

Now a guide to the intricate drawings and plans associated with countless engineering and construction projects carried out by the Stevenson family has been made available online, offering the opportunity to see their incredible craft in a fresh light.

Around half of the National Library of Scotland’s collection of more than 4000 items documenting the Stevenson family’s contribution to Scottish engineering history have so far been uploaded to a new online map which plots records of archive items onto their corresponding locations around the country.

The map – which eventually will include the remaining 2000 maps and documents - offers an insight into the extraordinary extent of the Edinburgh family’s influence on Scottish life, from helping to keep those at sea a little safer, to opening river routes and harbour entrances to ease the passage of vessels, and canals and bridges.

Indeed, points out Chris Fleet, Map Curator at the National Library of Scotland, while the Stevenson family may be best known for constructing every lighthouse in Scotland, the plans and designs show that element only made up around 5% of their work.

“By far the greatest proportion of their work was far more mundane but important aspects of infrastructure like harbours, breakwaters, slipways and even railway and canal projects,” he says.

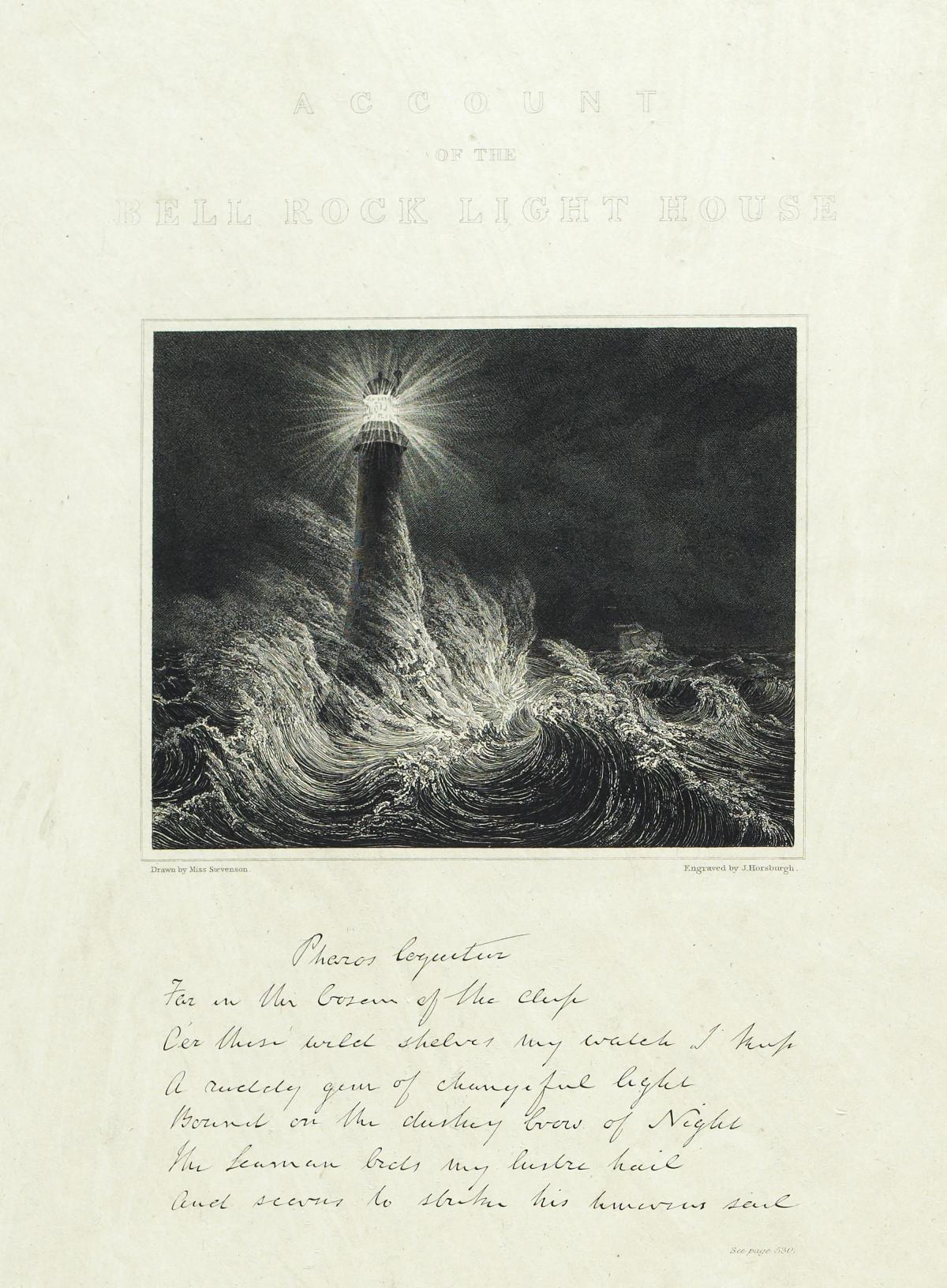

“But it was their initial work in early 19th century on the Bell Rock lighthouse that gave the family massive publicity.”

The long and dangerous reef lying 12 miles east of Dundee and on the route for vessels navigating to and from the Firths of Tay and Forth, had been a cause for concern for decades and was linked to the loss of up to six ships every winter – and as many as 70 during one particularly stormy season.

However, it was the sinking of HMS York in 1804 with the loss of all hands that sparked calls for a lighthouse to be erected on Bell Rock; a daring proposal given the surface of the rock typically lies under 16ft of water, emerging only at low tide.

Glasgow-born Robert Stevenson had already worked as an apprentice to his step-father Thomas Smith, a lamp-maker appointed by the new Northern Lighthouse Board to construct and manage four lighthouses.

Aged 19, Stevenson had already left his stamp on the nation’s most treacherous stretches of coastline when he completed the erection of a lighthouse on Little Cumbrae in the Clyde.

He was in his mid-30s and had already crafted plans for a Bell Rock lighthouse when the HMS York disaster prompted calls for it to be adopted.

In a remarkable feat of endeavour and bravery, workmen defied the crashing waves surrounding the rock to begin their excavation work in 1807.

It would take four years of construction before the tower’s first beam of light shone – alerting countless sailors down the years to the risk and saving innumerable lives in the process.

The 36m tall white and black lighthouse remains the world’s oldest surviving sea-washed lighthouse, although its keepers moved out in 1988 and its light is now operated from the Northern Lighthouse Board offices at 84 George Street – a short distance from the New Town where the Stevenson family made their base.

Robert Stevenson went on to serve for nearly 50 years as engineer to the Northern Lighthouse Board, overseeing the construction and improvements to lighthouses from Sumburgh Head in Shetland, to Barra Head at the southern entrance to The Minch and Scotland’s southernmost point at the Mull of Galloway.

His talent for civil engineering ran in the family: his sons, Alan, David and Thomas – father of Robert Louis Stevenson – would go on to follow in his footsteps.

The brothers’ lighthouses stretch from the most northerly lighthouse in the British Isles at Muckle Flugga on the Island of Unst – 165 years old and still going strong - to the equally curiously named Chicken House lighthouse on an isolated rocky island at the southern tip of the Isle of Man.

At the most isolated, Sule Skerry, 40 miles west of Orkney and designed to aid the passage of vessels through the Pentland Firth to and from the Iceland seas, keepers would spend a lonely month at a time with just seals, puffins and crashing waves for company.

Perhaps the most challenging, however, was the construction of Skerryvore lighthouse. The graceful tower designed by Alan Stevenson is the tallest lighthouse in the country, measuring 46m of solid granite which were quarried on the Island of Mull throughout its six years of construction.

Huge blocks of stone were ferried by tender to Hynish on Tiree to be dressed and shaped to ensure they fitted perfectly into place, before being taken to the site overlooking a reef of treacherous rocks around 10 miles south west of the island.

The family firm was eventually passed to David’s sons, David Alan and Charles, in the 1880s, and grandson, Charles.

But while they continued to specialise in lighthouse design until the 1930s – including lighthouses as far afield as New Zealand and Japan, the family also undertook a wide variety of work which helped transform travel and improve infrastructure.

Mr Fleet points out that the maps and plans held by the Library show not only the remarkable attention to detail and vision of each designer, but in some cases the changing face of the locations such as harbours which were redesigned to make them safer and easier to navigate, rivers where work was carried out help improve the flow, and roads, bridges and canals which opened swathes of the nation to economic development.

However, perhaps the biggest impact of their work is missing from the collection of maps, plans and documents: the countless lives their engineering skills saved.

Mike Bullock, Chief Executive of the Northern Lighthouse Board said: “For over 150 years Robert Stevenson and his descendants designed and built the majority of Scotland’s Lighthouses.

“They constructed wonders of engineering that have withstood the test of time and the elements.

“You only have to look at Robert Stevenson’s Bell Rock Lighthouse, which since 1811 has been continuously safeguarding ships and the lives of their crews and passengers, to recognise their remarkable contribution to our nation.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here