As Abertay University in Dundee becomes the latest Scottish uni to announce it is closing its bar in the face of changing student tastes, our writers recall when the student union was the place to be

Edinburgh University

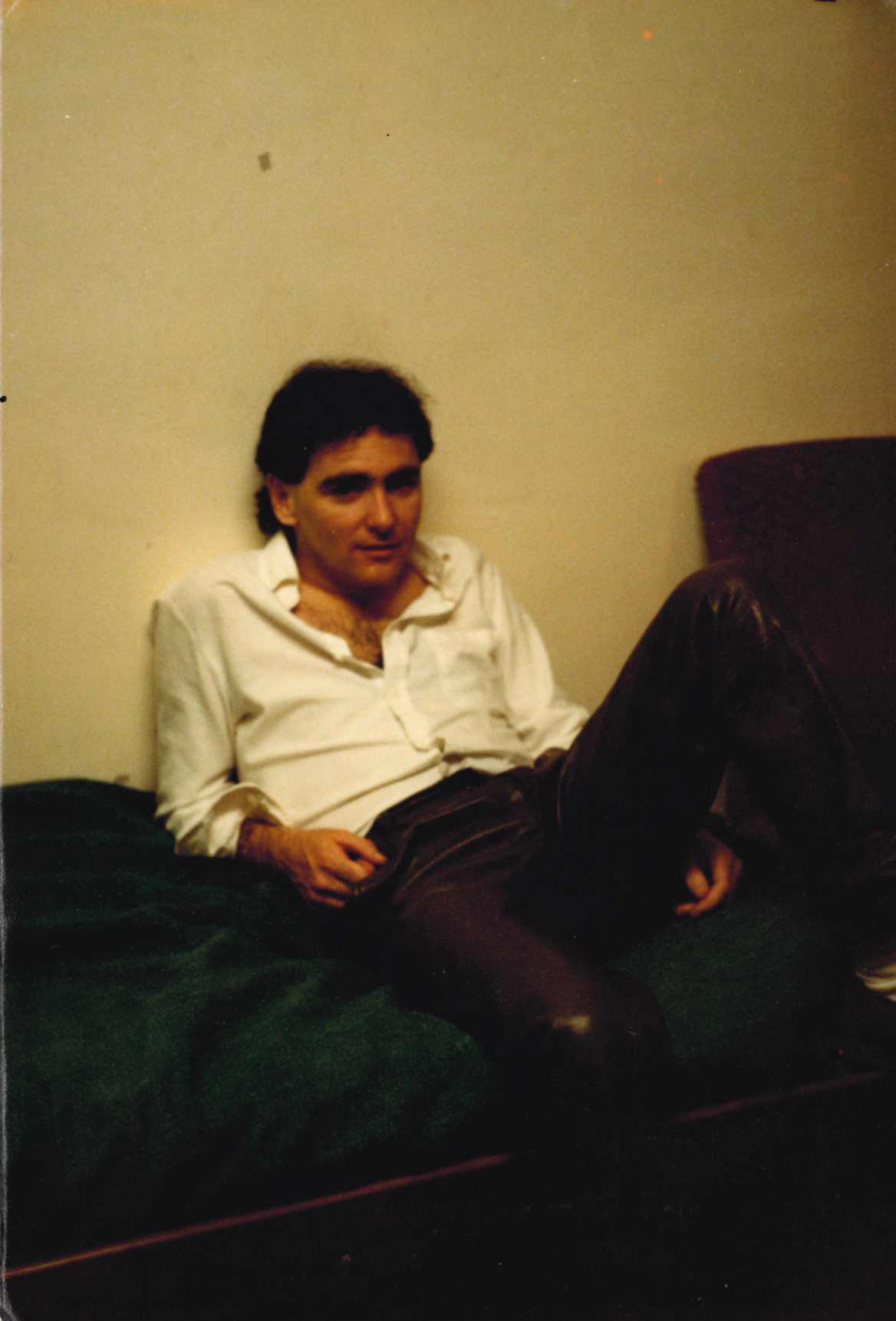

Drew Allan

ACCORDING to Plato's Theory of Forms, the physical world is not as real or true as timeless, absolute, unchangeable ideas. This I vaguely remember from one of the few lectures I attended on the Aesthetics and General Philosophy course at Edinburgh University, which I was taking, in 1974/75, alongside English Literature. In the physical world of the Students Union in Chambers Street, what was true and timeless was the natural order of red, yellow, green, brown, blue, pink and black. Because it was there that I first developed a lifetime's fondness for snooker.

I had started university life in the capital exactly three weeks after my 17th birthday. I was much too young be swapping life with mum and dad and little sister in Perthshire for a disciplined, academic regime. I was also too young to legally drink – I could barely pass for my true age, never mind 18 – but I could do so in the union, as long as I was in possession of an NUS card, which I was. It was a boon for a shy, lonely lad in the big city, who didn't have recourse to pubs and clubs.

Those first few weeks were the worst. It is unfortunate that the start of the university year coincides with the change to the long, dark nights. The union was a haven, of warmth, light, company ... and beer. And, wonder of wonders, full-size snooker tables.

I never did get very good at the game – my record break is still on a par with the average hacker's golf handicap – but I did become rather adept at the beer thing. I met the challenge of peers and learned how to drink a pint in a oner (the trick is not to keep gulping, but to open the gullet) and do the yard of ale (here the secret is to keep twirling the bowl at the bottom).

I'd like to say I made friends for life here; I didn't, not friendships that lasted 40-plus years at any rate. But the student union offered an escape from the loneliness of a cramped room in the Halls of Residence and studies I had no great interest in pursuing. And there, I learned to be comfortable in the company of others, and that's something that never leaves you.

Unlike the yard of ale thing. Definitely wouldn't try that now.

Queen Margaret Union

BY the time I arrived at the steps of the Queen Margaret Union (QM) for the first time, for Fresher’s Week 1993, I’d already made one of the big decisions facing Glasgow University students of the day. Back then every student joined the union, and which union you joined – there were two – said everything about what sort of person you were, or intended to be. In my day the Glasgow University Union (GUU), on University Avenue, had a reputation for Rugger Buggers and young Tories. Some folk still referred to it as the “men’s union”, for goodness sake, which it had been until 1980, when finally – under duress – it allowed women in. This was not the place for a Smiths-obsessed, Simone de Beauvoir-reading 18-year-old from Glenrothes who was the first in her family to go to university.

The QM was everything the GUU wasn’t. It was founded “by women, for women” back in 1890, providing a place for them to gather, study and thrive at a time when they were still excluded from many aspects of life, both inside and outside the university. Men had been admitted for some time by the time I was a student 1990s, but it retained a radical feel.

Crucially, where the GUU seemed like the epitome of the establishment, the QM was modern and cool, not least because of the music scene it fostered. Nirvana had played a legendary gig there in 1991, while the likes of Smashing Pumpkins, Hole, Garbage and Belle and Sebastian would go on to do so.

Even the buildings looked radically different. While the GUU was housed in a rather overblown mock-castle, the QM’s home at the end of University Gardens, a shabby 1960s brutalist behemoth, seemed to reflect and embrace its membership.

During my four fantastic, happy years at the university the QM was an integral part of life. I went there most days, eating lunch in the cheap canteen, meeting pals for pints of snakebite at Jim’s Bar, dancing like a loony to James, The Prodigy and 2 Unlimited at Cheesy Pop, the long-running club night. I snogged unsuitable boys and cried in the toilets. I went to meetings about how to stop the government freezing the student grant, blissfully unaware in our outrage of how much more difficult things would get for those who came after us. I nurtured friendships that are still an integral part of my life.

I didn’t even step foot in the GUU until my final year, when a pal persuaded me to go to Daft Friday, the famous end of term ball that seemed to represent everything I stood against. I ended up having a wonderful time, of course, especially since neither the GUU, nor its members, lived up to the stereotypes I’d clung to. As I looked at the names of the debaters on the wall – including Donald Dewar and Charles Kennedy, people I respected – I remember feeling a tinge of regret that I had so wholeheartedly rejected everything the place had to offer.

Over the years, things have changed, of course. Students aren’t so keen on student unions anymore; they’re more likely to be found at the gym or scrolling through social media in overpriced, purpose-built off-campus accommodation that they'll be paying off forever. The QM has faced significant financial challenges and was even threatened with closure. But it warms my heart to see folk still queuing up on those ugly 1960s steps for gigs: just this week the mighty Edwyn Collins played. Long live the QM.

Glasgow School of Art

Eva Arrighi

I enrolled at The Glasgow School of Art in 1989, when Glasgow was revelling in its title of City of Culture. The Vic was and remains possibly the coolest student union in Scotland, but back then it was as grungy as a Seattle battle of the bands. I don't think more than three toilets worked at any given time, which made for supersonic bladder control when the queue to the loos reached up the stairs on a Friday and Saturday nights.

It was wonderfully scuzzy, nearly always sweaty but the drinks were cheap and the crowd was young, lusty, beautiful and by degree interesting or pretentious. It was a wide, giddy spectrum of inappropriate bedfellows all of whom had fantastic hair.

Those were the nights when Glasgow's indie glitterati lined right up along Renfrew Street to gain entry (you needed signed in by an art student which made you very popular if you had a GSA matric card)

The wait could take time, but no matter, everyone was there for Andrew Divine's genre melting sets with 1960s garage nuzzling next to indie, Northern Soul classics and techno.

During the week it was less high octane but no less boozy, and you could mingle with your tutors (when I say mingle I mean get pissed). There is nowhere else that a conversation could include Baudrillard, The Byrds, Barthes, Beuys, Bowie, Buckfast, Baldessari and Bataille and everyone would know what you were talking about. It was and remains a very very special place.

Napier University

Susan Swarbrick

IT’S a warm June day, barely gone lunchtime, but already we’re squeezed into a horseshoe-shaped booth at the Napier University student union in Edinburgh, sunshine streaming in through the big bay window. Earlier that morning the last of our second-year coursework was submitted – a group presentation for a PR and advertising module – and still dressed in the smart suits that we imagine we’ll one day wear as high-flying execs, my coursemates and I are celebrating with a liquid lunch.

Someone proposes a kitty, we all chuck in a fiver and soon the table is groaning under the weight of pints of lager and vodka chasers. It’s 1997 and I’m 19 years old. An uninterrupted summer stretches ahead. I feel giddy with anticipation.

In those days, the Napier student union was housed in a converted Victorian mansion just off Bruntsfield Place. We would troop past swish Montpeliers around the corner with its well-heeled grown-ups sipping wine and popping olives into their mouths.

Our student union bar was little more than an oversized living room. It was cosy and did the job. But it wasn’t quite on the same scale as Teviot Row House at the University of Edinburgh which we also frequented.

The Gothic-style building of Teviot, which opened its doors in 1889 and is still going strong today, meandered over several levels and was architecturally stunning, albeit mainly appreciated through a fug of alcohol.

Prices were a steal too. Back then it was rare you paid more than £1 for a pint. Vodka shots were 50p. This being the mid-1990s, Smirnoff Moscow mule and lemon-flavoured Hooper's Hooch were all the rage. On promo nights you could get them for £1 a bottle. What a sticky mess they made.

There was a cash machine outside Teviot that dispensed £5 notes (surely one of the last in the country to do so?) which came in handy when you were down to your last few pounds.

What more did you need than cut-price alcohol and Britpop? Granted, this wasn’t always a prudent mix. I remember being sick on the Teviot stairs one night. It was a dreadful, full-scale projectile vomit, like something from the Exorcist. Mostly vodka.

As the bouncers swept in, I steeled myself, but it was a guy, swaying unsteadily on his feet nearby, that they huckled out the door as he loudly protested his innocence.

I stood for a moment listening to the distant strains of Pulp from another corner of the building. The only witness to my dastardly deed was a taxidermy moose head which gazed back glassy eyed from the wall above. I held a finger to my lips, whispered “shhh!” and fled the scene.

Aberdeen University

Mark Smith

Late 1980s. A Friday. Out we go. To the student union. Four pints. Five. Six. To a nightclub. Dancing. The Smiths. New Order. Etc. To the takeaway. Pizza. Chips. To the night bus. Home. Total bill for the night: a fiver.

I’ll break it down for you. In the late 80s, a pint at Aberdeen University’s Union was around 60 pence. Entry to the union, and the nightclub upstairs, was free with student ID. And if you wanted something to eat on the way home, it’d cost you about £1.50. Therefore: you could have a night-out for one five-pound note.

What did you get for your money? A choice of bars. The one in the basement of the union was called the Dungeon. The walls were painted black, to avoid stains, and the beer was served in plastic beakers, to avoid incidents. There was a story about some guy who died in the toilets after sniffing Tipp-Ex, a liquid students used to correct mistakes before the invention of the delete button. I never found out if the story was true.

Upstairs from the Dungeon was Sybil’s, allegedly a cocktail bar where you could allegedly pick up people you fancied. And upstairs again was the Neill Lounge, a nightclub where arms flailed to the words of Robert Smith and Ian McCulloch. Later, when dance and drugs took over, there was another place through the back of the union called Phase 3 where was the soundtrack was the KLF.

Summer 2019. The old union, which was on Broad Street, is closed now. There is a new union somewhere else in Aberdeen. Except it’s called the hub (lower case t, lower case h). There are shops. A Subway. A Baskins Robbins. You know where this is going, don’t you? This is a piece by an old former student moaning about how things aren’t as good as they used to be, isn’t it? Of course it is.

Leeds University

Brian Beacom

OCTOBER 1980. Sitting on the wall across from the Student Union bar at Leeds University, two young men are gazing at the vast Georgian building. They are clearly considering how this early learning centre for young adults will advance their mindset, promote their spiritual enlightenment and herald a new dawn in cognitive human growth – while all the time noting the sheer volume of gorgeous girls passing through the doors.

One of those young men was me. Next to me was an East Londoner, Steve, whose head was in the same place; ie, a place called Fun. We discovered we were on the same course, and soon-to-be football team, and direction in life. Before an hour was over we were a confirmed duo, exploring the building and our new life. And it was wonderful, in a slightly smelly-stale beer-and-last-night’s-Cornish-pasty remains sort of way. It was also wonderfully frantic, like a major train station at rush hour, filled with teenage fish out of water who’d left the suburbs or Bolton or Newcastle behind, now all intent on buying books, pens, chocolate bars – and their entry into a whole new way of life.

We couldn’t help but smile at this building awash with different types of people, some trying desperately to look like the students they had now become; (the fashion of the day for females was school blazers, (ironic, I know) and donkey jackets for men. The more middle class the student, the more hoi polloi the look. There was also a smattering of young men trying to look like they’d once tried out for Curiosity Killed The Cat. Or young women who wanted to be Siouxsie. Or Toyah. The ethnic mixes were fascinating; Glasgow never revealed so many colours at this point.

What was astonishing was that this bustling emporium was housed in the middle of reactionary Yorkshire, a land of Hovis, Tetley tea bags and Geoffrey Boycott backwardness. The union building’s security guard, with the broad accent, and his ‘You don’t want to be sitting there’ commands confirmed his task in life was to kill fun.

But that contrast of Victorian outlook and new wave student possibility only served to heighten the excitement. And the building became a place to savour. It was the place to buy shampoo, books by Sartre, Eurotrain tickets and to buy time. It was a place to drink, to eat and to snog the person who’d become the most important person in your life.

This was a palace of eternal promise, to meet new best pals, to enjoy subsidised drink and to talk for the longest time about Thatcher’s witchcraft or Leeds United’s chances – or the fact the The Pretenders didn’t have enough songs to complete their set the previous week and had to play Brass In Pocket twice.

It was also a great big gang hut. It was a place to play table football or pool or stimulate the brain with Space Invaders, to mock Andy Brennan’s duffle coat which he wore, with t-shirt, every day of term regardless of the weather. And it was amazing.

Me and the Cockney are still best friends, partly because we grew up in the same home. That home was the student union building.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here