It was an evening that began like any other night shift. Firefighters handed over at 6pm to start what they thought would have been a fairly routine night.

However, within two hours 19 men had lost their lives and 33 children were left without fathers when a whisky bond warehouse in Glasgow went up in flames. It was one of Britain's worst peacetime fire services disasters, and remains so to this day.

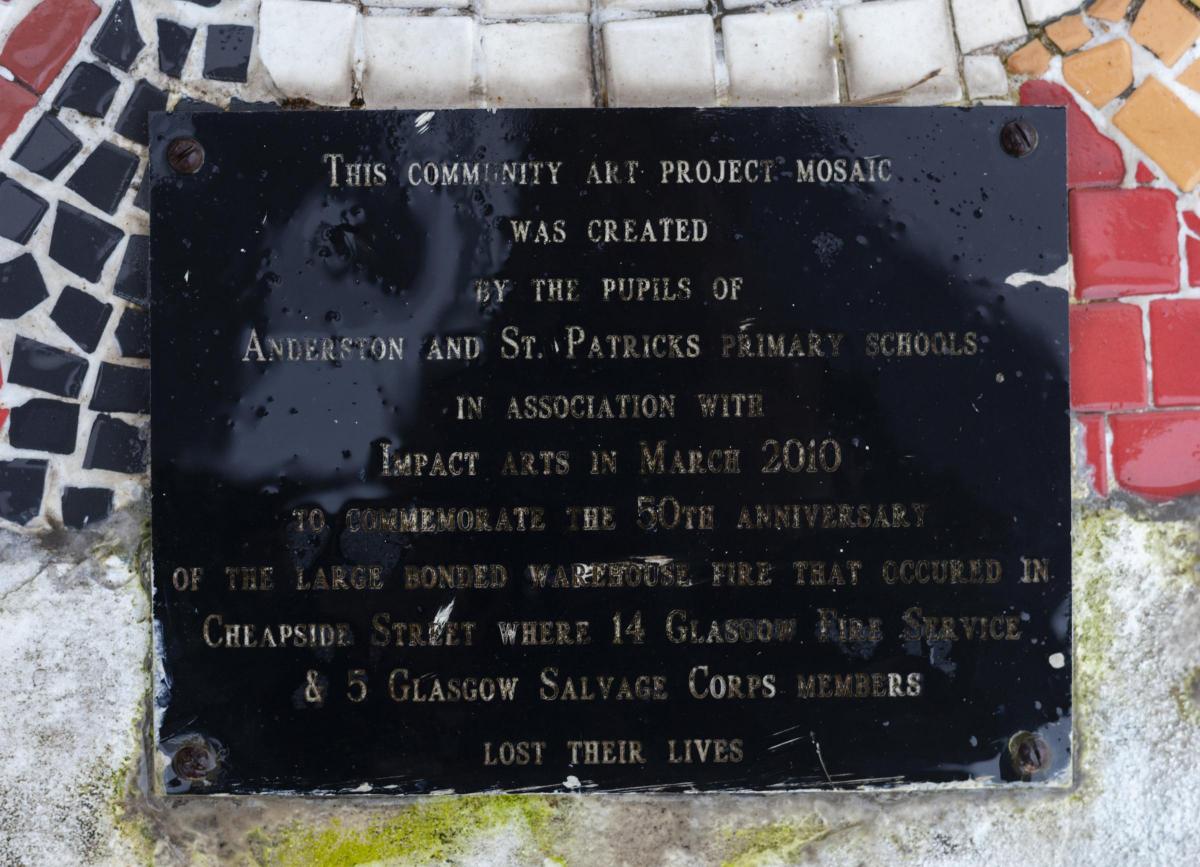

Most of the loss of life happened within moments of crews responding to the Cheapside Street fire on March 28, 1960.

Such was the ferocity of the fire that a glow from the flames lit up the night sky over Glasgow, which was beginning to earn the name of Tinder Box City given the number of major blazes it had suffered. As fire broke out at Arbuckle, Smith and Company, clouds of alcohol fumes drifted through the air. The fire burned for hours, but the toll on families who lost relatives lasted a lifetime.

Whisky barrels rolled out into the streets and smashed, creating rivers of burning alcohol. Fourteen firemen and five salvagemen were killed.

Read more: Firefighters reject ‘unacceptable’ pay deal

It was shortly after 7pm that evening when George Pinkstone, the depot superintendent of the Eldorado Ice Cream Company, smelled burning wood and went into the street to investigate.

He could see smoke coming from a second-floor window of the adjoining bonded warehouse. It contained more than one million gallons of whisky in vats and barrels, and more than 31,000 gallons of rum.

After dialling 999 at 7.15pm, Mr Pinkstone went to the bond to alert the Customs officer and foreman who were loading 1000 cases and 40 casks of whisky on to a lorry.

The first crews arrived at 7.21pm, from West and Central fire stations, and a tender from the Glasgow Salvage Corps arrived at the scene. Meanwhile, the fire boat St Mungo was making its way from the Marine Fire Station at Yorkhill Quay.

More fire chiefs arrived on the scene and having been fully apprised of the situation increased the number of pumps to eight. This message was sent at 7:49pm – but seconds after it was transmitted a large explosion blew out the walls of the premises virtually destroying it.

Firemen had entered the warehouse to search for the seat of the blaze. In nearby Warroch Street, at the rear of the warehouse, firemen had spotted flames through a barred ground floor window.

A ladder was put against a wall and a fireman was about to put a hose on the flames when the 60 foot-high walls of the central section of the warehouse blew out on to Cheapside Street and Warroch Street.

Three firemen were killed instantly by falling rubble – in Warroch Street the death toll was even higher. The collapse of the wall there claimed 11 more lives.

The explosion was also a devastating blow for Glasgow Salvage Corps, which lost five members in Warroch Street.

It was to be the worst peacetime fire disaster, but it created a lasting legacy as the events of that night eventually led to the way buildings were designed and fires tackled.

Jim Smith was just five years old and his sister Maureen not even born when their father was involved in the blaze.

Now 60 years on, they will remember the poignant anniversary and the part their father played on the night.

“All I can remember is the women crying,” said Mr Smith, from Glasgow's south side. “My father Joe was a salvageman and in those days we lived in tenements at the back of the Salvage Corps base in Albion Street. All the families lived there and the children used to play in a large central back court. We all knew everyone. We grew up with them.

“To be honest I was so young that I didn’t know a huge amount about what had happened – just that my friends' fathers had died. Growing up it wasn’t even something which my father talked about. I suppose it was a case of a stiff upper lip in those days. It was only in his later years when he became ill that he told me he was pulled out of rubble by a police officer after the wall suddenly collapsed.

“The injured were taken to Glasgow Royal Infirmary and my mother went up to see him. When she arrived a doctor said to her ‘I’m sorry but he has gone.’ For a split second my mother didn’t know what he meant and if he had died when the doctor said he’d gone home.”

Read more: James Watt fire remembered 50 years on

Their father Joe recalled in a book about the disaster, Tinderbox Heroes, how he was moving a line hose when the Salvage Corps crew approached him: “I needed a hand so I said to them, kidding them on, ‘Where have you been?’. They were about 15 to 20 feet from me when the building exploded. When I came to I had debris all over me. I was on the ground but I didn’t know much about that.” Mr Smith Senior died six years ago aged 85.

A memorial service had been due to take place at Glasgow Cathedral on Friday but has been cancelled due to coronavirus advice. It was to be followed by an event at the official Cheapside Disaster memorial at the Necropolis.

Mr Smith added: “For years my father took me to the Necropolis to remember his colleagues. I was just a small boy when we first went, but we never missed a year. It was just something my father had to do for his buddies that he had lost."

• Those who died were Glasgow Fire Service members John Allan, Christopher Boyle, James Calder, Gordon Chapman, William Crockett, Archibald Darroch, Daniel Davidson, Alfred Dickinson, Alexander Grassie, Ian McMillan, George McIntyre, Edward McMillan, John McPherson, William Watson.

• Glasgow Salvage Corps Members Gordon McMillan, James McLellan, James Mungall, Edward Murray, William Oliver.

The rise of Tinderbox City

Scotland’s largest city earned itself the name Tinderbox City following a series of fires spanning four decades, some with devastating consequences.

Fires, including the Arnott Simpson department store in 1951, saw major landmarks disappear from the cityscape. Worse was to come when 22 furniture factory workers were killed in the James Watt Street fire in 1968. It was closely followed by the Kilbirnie Street fire of 1972 which left seven fire service personnel dead.

Former station officer James Smith believes that Glasgow may have been a victim of her own Victorian architectural heritage. While cities such as London and Coventry were extensively bombed during the Second World War, Glasgow suffered little damage in comparison.

It left Glasgow with a rich legacy of 19th Century buildings, but the downside of this was the city had old industrial buildings remaining that may have been destroyed elsewhere.

“There were warehouses like vast storage caverns so big that sprinkler systems, if there were any, couldn’t do their job if a fire broke out,” Mr Smith said.

At the time of the Cheapside Street fire, crews were working a 56-hour week with little time off between shifts.

At one time firefighters were required to be on duty in Glasgow's theatres following death of 60 people when a stampede broke out in the 1860s.

"When I first joined the fire service we still did theatre duty. We were to look at exits for people, stop the artists smoking on stage. On one occasion I was on duty when Marlene Dietrich was appearing at the Alhambra. As most people know she was rarely seen without a cigarette. I had a look around the stage, looked at the area back stage and said I would need to see where her ashtray would be. She was able to smoke and her people said to me 'Miss Dietrich says thank you'."

Mr Smith, 78, added: "To set the scene Glasgow was a very busy city at the time with three main stations – the south, central and east where I worked for some time. Another part of the problem was the massive rehousing project which was under way in parts of the city. It saw people move out to the likes of Pollok, Drumchapel, and East Kilbride. It left us with more than 100,000 empty tenements.

"Add that to the factories and warehouses and and it was an extremely busy time for the fire service. Empty tenement blazes were pretty common and it only took one person in the street to say they thought there was someone in the building and we had to carry out a full search.

"It was an era that saw multiple deaths in the fire service. In the coming years it wasn't the case of the fire service needing to change – they just deal with whatever is in front of them at the time. All work they faced was dangerous.

"As time went on it was the designers, planners and city architects who were having to change the way buildings were constructed and that led to the city becoming a safer place."

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel