Powerless

(def: without the power to do or prevent something)

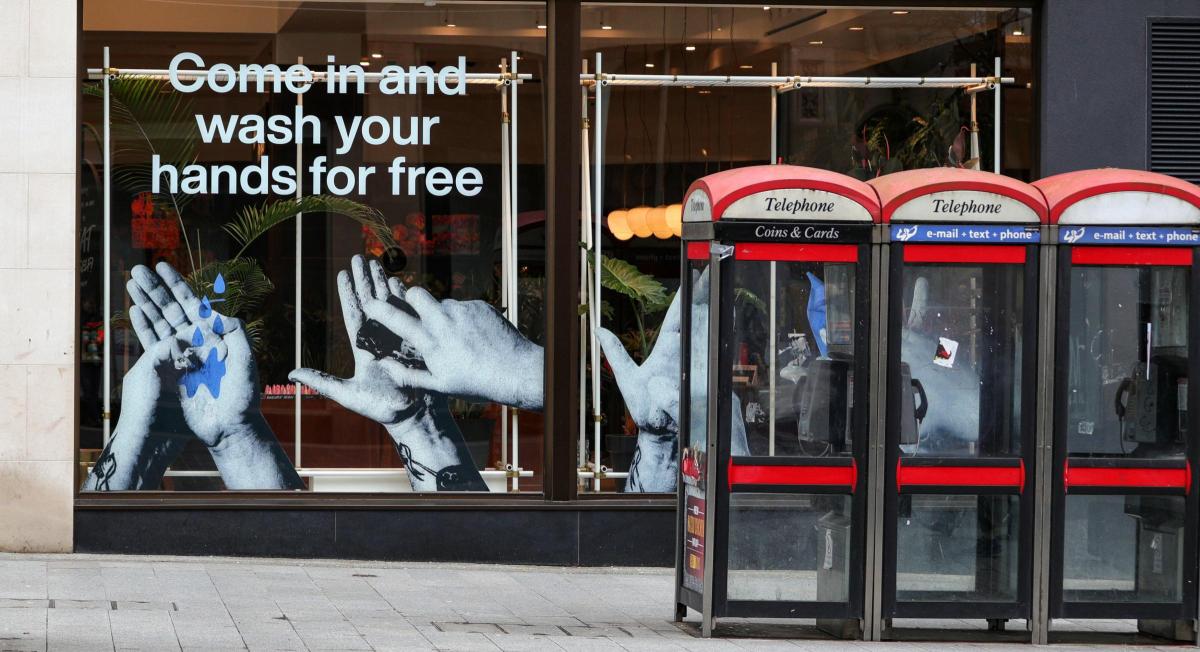

These are the days when the chief powers it seems we have are the ability to wash hands and move through the world at a two-metre distance from other humans. You wake up, you wash your hands, you go on social media, you wash your hands again, and one of the things you feel, if you’re anything like me, is helpless and somehow inadequate.

You wonder, perhaps, if you were a nurse or a doctor you would feel more or less powerless. Then you remind yourself that powerless is a word NHS workers have frequently used. A doctor in the northeast of England, for example, who says: “I feel powerless. These patients are like nothing else I have treated. All the time they are so delicate, my normal intensive care instincts don’t apply.”

When Nicola Sturgeon talks about how the rising death toll caused by the virus makes us feel, this is the word she uses: “I know listening to this might leave you with a feeling of powerlessness as well as an acute and deep feeling of sadness.”

Read more: Feeling wakeful? The Covid pandemic, a recipe for insomnia

There’s good reason for her to talk of powerlessness – because that is what many of us feel. It’s what relatives talk of when they describe what it’s like not to be able to see a loved one who is dying in hospital from Covid-19. We feel powerless too when we discover that the people in power, Boris Johnson and his recent government, as the recent Sunday Times expose revealed, failed to prepare us for the pandemic.

Almost always Sturgeon follows up her use of the word powerless with a reminder that “None of us are powerless and all of us have some control here. We all have some power against this virus. By following the rules, by staying home ... we are all making a difference”.

But that’s not a satisfying type of power. I’m not sure that many of us out there would say, as we wash our hands and avoid our friends, that we feel very much less helpless. We can tell ourselves we are doing something in this fight, but it doesn’t feel like much.

That’s partly because we are attached to a particular idea of power. We are a society that is all about doing things, in which the idea of doing nothing is anathema. Yet sometimes doing something about a problem can be merely to stop doing what we normally do.

It’s hard to feel this as any kind of power. After all, the death toll is still rising. There is, as Nicola Sturgeon expressed this week, still huge uncertainty over when and how we will come out of lockdown. Worse still, it’s clear we are heading into economic depression and previously unimaginable levels of unemployment. Those who have lost jobs, and those of us who fear losing our jobs, all feel powerless to know how we would find new work post-pandemic.

Yet, we are also seeing the power of inactivity. We are seeing not only how it can bring down the rate of infection of a disease, but the greenhouse gas emissions that threaten the future of humanity. Carbon Brief recently published projections that showed that the coronavirus crisis could trigger the largest ever annual fall in CO2 emissions, more than during any previous economic crisis or period of war – though even that “would not come close to bringing the 1.5C global temperature limit within reach”.

Both coronavirus and the climate crisis can make us feel powerless. Yet both also provide us with a reminder that there is power in doing nothing, or rather less. It feels as if we are being prompted to rethink our ideas about the inherent goodness of activity, productivity and work. Recently, talking of how we might be being called on to do less, an interviewee quoted to me the last line of John Milton’s On His Blindness: “They also serve who only stand and waite.”

Something to repeat over to ourselves, as we wash our hands and wait.

Dim

(def: not clearly recalled or formulated in the mind)

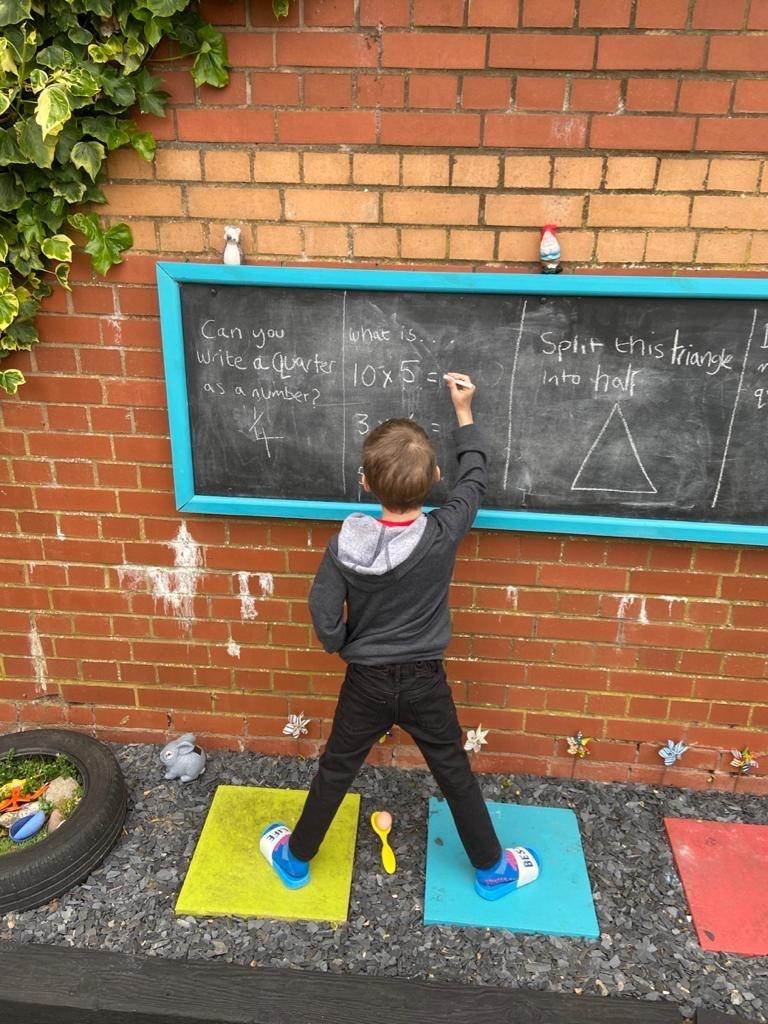

That rising feeling, as you sit down to give your kids a home-schooling chemistry lesson, that you may have forgotten literally everything you learned back when you were in the classroom. Someone must have wiped your brain. Even the subjects you were good at are gone.

Bright side? You've got all the joy at learning the periodic table ahead of you again.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here