Burnt out

def. exhausted or in poor health due to overwork

There have been many times over the past few weeks when it’s seemed to me that the much-talked of coronavirus slowness was a myth, or something I’d failed, personally, to grasp. At first I thought I was the only person feeling this, but then I started to realise many others were too. People I come in contact with kept telling me they felt more busy, not less – and I’m not just talking about key workers, but a wide demographic in terms of income and occupation. These people, of course, were mostly not those who had been furloughed or lost work. They were also, mostly, people who had kids.

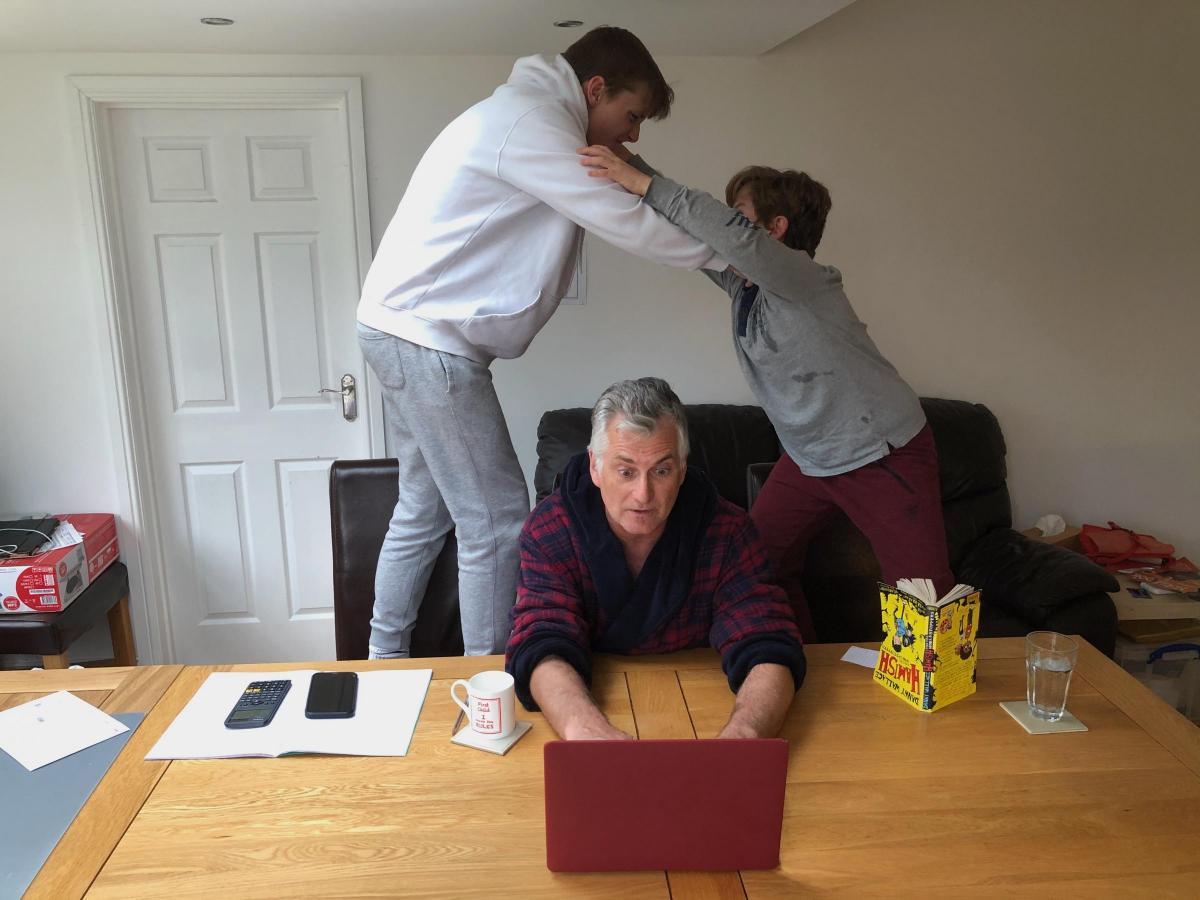

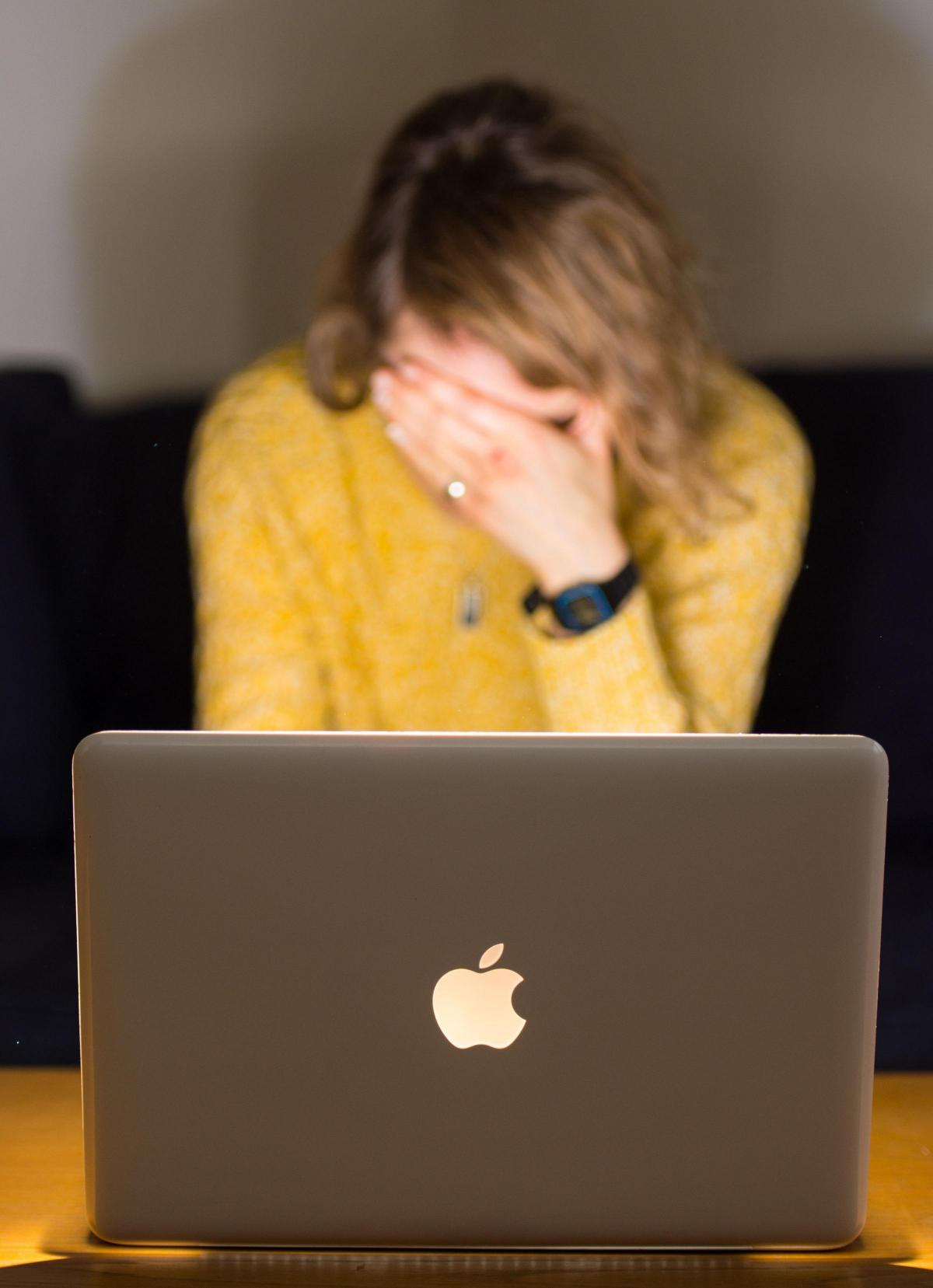

Last week, this paper reported that millions of people forced to work from home “may be at risk of burnout as their work-life balance is turned upside down”. It may seem hyperbolic for us to talk about feeling burnt out by just the mere challenge of trying to work and home-school our children, but there’s a pace of life for many of us here that’s undoubtedly unsustainable. I’m waking at 5am to get time to work before home school starts, and I’ve talked to many others stretching out their days, doing their double shifts.

We may be moving around less, but many of us are as busy. When our cars, trains, planes and workplaces stopped, tech rushed in – Zoom, Microsoft Teams, streamed talks and events – and not just for us, but also for our children. On Facebook this week I found myself joining in on a thread, started by a parent with a small business, who complained that she was struggling to get to grips with the confusing system of online school assignments being sent out to her kids.

It echoed my own feelings that one of the biggest challenges of the recent weeks had been to try to work out what my eldest son, at secondary school, is expected to do. He wants to manage it himself, but it seems unmanageable. Work arrives on different platforms – via email, Teams, website downloads – with assignments often not where you expect them to be.

Reports into lockdown delivery of online education are revealing a staggering difference between individual schools, and crucially between the state and private sector. Neil Mackay, writing in this paper last week, reported that a survey by the Scottish Secondary Teachers’ Association before Easter found that less than half of children were engaging with teachers. He described how one teacher had told him she only had four children out of 33 join an online lesson. I recognise that. My son was one of three in such a low turn-out class and only because we happened to spot the message when it came in.

And I understand why kids aren’t engaging. It feels to me as if our children (and us too) are being thrown in at the deep end and the swimming skills they have to learn are a form of digital self-management. Some may emerge at the end having learned practices of self-organisation, but many will not. Some, in some houses, have no access to digital learning at all. I’m not blaming the individual teachers, many of whom are locked in a struggle of trying to deliver learning through new technology platforms, while also possibly juggling their own kids. I also think it’s wrong to blame parents. The wider system itself should deliver a lot better for all kids.

I also, however, think that children are part of a wider world, and above all we need to be working out right now how to make this better for all of us in the new normal.

The truth is I’m someone who believes in slowness. I take on board Danny Dorling’s argument that evidence shows we are already going through a period of technological slowdown, economic deceleration and declining growth.

But it feels as if even in this pause, life for many of us is only getting more digitally hectic. We could resist that – let our kids get bored and drop out at work – but most of us are still struggling to earn and the answers to many of our current problems demand work. They also require rethinking what’s important – and, what with home school and homework, many of us are too busy for that.

Feeling wakeful? The Covid pandemic, a recipe for insomnia

Vicky Allan is feeling grateful. How coronavirus is showing us a new gratitude

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel