Coronavirus isn’t the first time humanity has faced a global crisis. We’ve been here many times before – and each time we’ve responded by creating the greatest art and literature the world has ever seen. By Writer at Large Neil Mackay

THE one thing we can take hope from in these perilous times is that we’ve been here before and we’ve come out the other side.

We just need to look at culture down the ages – from stories, paintings and songs of long ago to the movies and TV shows of today – to see that the fear of death, disaster and End Times has always preoccupied humanity.

We’ve been writing, painting and singing about each of the four horsemen of the apocalypse – death, famine, war and disease – for millennia.

Crisis and catastrophe often create the best art, however. Humans need art and culture to make sense of pain and suffering.

Coronavirus will inevitably prompt a wave of great art – movies, novels, music and theatre – which will interpret and explain what it was like to be a human when the world closed down and sickness was everywhere.

In fact, we’re already seeing culture respond to the virus. One of the artistic highlights of the last few weeks has been a series of short TV dramas called Isolation Stories – subtle, sad, funny takes on life during the pandemic.

Origins

We see humanity struggling to deal with catastrophe and crisis in our earliest cultural offerings: our origin stories.

What’s the story of Noah but a Bronze Age disaster movie? Nearly all cultures have a flood myth. The Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh recounts a flood legend, as do Norse, Celtic, Native American and Aboriginal Australian myths.

The flood is a universal story of destruction and survival. It’s thought most flood myths have some root in reality. Perhaps a memory of the Ice Age. The biblical flood was possibly inspired by the “Minoan Eruption” of 1600BC when a volcano devastated what is now the island of Santorini. It was one of the largest volcanic eruptions in human history, triggering tsunamis which would have caused death on an unimaginable scale. The Minoan Eruption might also be the basis for the Atlantis myth.

Some of our greatest ancient literature is about mass death and ruination – from the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah and the Viking Ragnarök, to Homer’s Iliad and Virgil’s Aeneid, both recounting the fall of Troy.

Living with the permanence of disaster and devastation laid the ground for a cultural obsession with death which shaped our global religions. End Times lies at the heart of Christianity – the final book of the Bible, Revelation, is also known as The Apocalypse, after all.

The dance of death

Nothing left such a lasting scar on human culture, though, as the pandemics of the second millennium: the Black Death of the 1300s, the plagues of the mid-1600s, the cholera outbreaks of the Victorian age. For hundreds of years, until the coming of modern medicine, death by infection was commonplace. Disease, fear and grief fed into culture in extraordinary ways.

One of the greatest works of literature is The Decameron by the Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio – an immediate and lasting response to the Black Death, which ravaged Europe, killing half the population between 1347-51. The Decameron tells of a group of aristocrats who retire to a country house to wait out the plague. While in self-imposed quarantine they tell stories to pass the time. If there’s one moral to the tales it’s this: Death doesn’t care who you are, it’s just a matter of luck and timing when the Grim Reaper comes knocking.

Without The Decameron it is unlikely we would have Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales – the foundation text of English literature published around 1400. One of its most famous stories is The Pardoner’s Tale, directly influenced by the Black Death. In the story, a group of men set out to kill Death – who, we’re told, took their friend and a thousand others – but instead, they end up killing each other. Nobody beats death.

But it was through painting that the pain and suffering of the middle ages found the most powerful expression. Memento Mori paintings (Latin for "remember you must die") were everywhere; the skull appearing in artwork after artwork, often alongside the hourglass showing the sands of time trickling away.

One look at The Triumph Of Death by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, painted around 1562, and you will immediately understand how omnipresent mortality and disaster were for our medieval ancestors.

It is a carnival of death on canvas. The painting is of a wasteland – Bruegel almost invents the idea of the post-apocalyptic. Everywhere skeletons are killing, capturing, torturing and humiliating men and women, from kings to beggars. It’s truly nightmarish – and remains terrifying.

The painting foreshadows the horrors of the 20th century. One could easily imagine SS guards as the murderous skeletons. In fact, nowhere is Bruegel more echoed than in the 2000 artwork Hell by the Chapman Brothers, featuring miniature models of Nazis engaged in appalling violence.

Paintings of the Dance Of Death, or Danse Macabre, became ubiquitous from the 1400s as Europe rebuilt after plague. In Danse Macabre art, Death leads people of all social classes to their graves. Life is fleeting, the allegory says, and what you have on Earth – wealth, power, beauty – is meaningless.

The Danse Macabre persisted as a cultural motif well into the modern period. Most people will associate it today with the music of Camille Saint-Saëns, and the theme tune to the TV show Jonathan Creek. With its scratchy, spooky violins and spidery, disorientating cadences, part of the Danse Macabre is even known as “diabolus in musica” – the Devil in music.

Pain on the page

When the novel began making a mark on culture in the 1700s, Daniel Defoe – a master opportunist – was quick to jump onboard and use the memories of his own brush with End Times as a child to artistic advantage.

Defoe lived through the 1665 plague which ravaged London. Three years after his success with Robinson Crusoe, Defoe wrote A Journal Of The Plague Year. It’s a fictional account of one man surviving amid the ruins of London, but historians, critics and scientists tend to agree that Defoe was pretty accurate in his rendering of real events.

Reading the Journal today is like seeing a mirror held up to coronavirus. The same fears, scandals, emotions and acts of kindness affected people then, as they affect us now. The rich thrive, the poor die; there’s isolation, quarantine and social distancing; nurses do the heavy lifting; there’s panic buying; conspiracy theories; science and government struggle to cope. What’s changed?

Early Romantic writers grappled with death on a daily basis – death in childbirth, infant mortality, outbreaks of cholera and typhoid. To many people, if you say “Romanticism” they’ll think of John Keats expiring of TB aged just 25 in 1821. Romanticism and death go hand in hand.

Edgar Allan Poe was the dark dandy of the Romantic movement. His story The Masque Of The Red Death both harks back to medieval horrors, and looks forward to the lurid post-apocalyptic sensibilities of the 20th century. It’s a perfect bridge in the art of the apocalypse.

The story tells of a prince who hides out in his castle and parties while the plague rages outside. It’s a clear lift from Boccaccio. At midnight, Death arrives in a blood-splattered robe. The masque ends with a castle full of corpses. Death, here, is like a slasher from a modern horror movie.

The Romantics also saw the apocalyptic possibilities of science. Electricity was cutting edge in the late 1700s. It was the era’s equivalent to artificial intelligence and robots (think how often today the apocalypse comes in the form of a sentient robot or killer computer). The cause célèbre of the time was experiments with electricity on dead frogs which made their legs kick. Such tinkering with nature had a profound impact on the young Mary Shelley.

Her novel, Frankenstein, is the response of a terrified society to the suffering science could unleash on humanity if unrestrained. The book also marks a turning point in apocalyptic art as plague takes a back seat to manmade threats. Both Frankenstein and The Masque Of The Red Death would become central parts of the horror movie canon in the 20th century – an art-form influenced by two world wars, the Holocaust, and the looming threat of global destruction posed by the Cold War.

Nuclear nightmares

The new science that frightened Mary Shelley was a terrifying fact of life come the Victorian era. HG Wells was waiting in the wings to become the purveyor extraordinaire of tales of mechanised apocalypse. His The War Of The Worlds tells of Earth’s near destruction at the hands of alien invaders. No longer did disease dominate our fears of destruction, but technology.

Wells’s contemporary, Richard Jefferies, spawned the post-apocalyptic novel with his book After London, which explores Britain after the collapse of civilisation.

The mechanised mass death of the First World War saw fears of the apocalypse seep into the deepest recesses of culture – most notably in the outpouring of war poetry by soldiers like Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. However, modernism itself was shaped by the trenches. The epitome of modernist poetry, TS Eliot’s The Waste Land, is a fractured meditation on death and decline. It ripples with apocalyptic imagery and sentiment, such as the line: “I will show you fear in a handful of dust.”

German art in the aftermath of the First World War was soaked in death and destruction. Painters like Max Beckmann and Otto Dix, veterans of the trenches, depicted a world of skulls and cruelty, crippled soldiers and deformity. European towns were at this time full of mutilated men, some with their faces hidden behind masks so bad were their wounds. German expressionist cinema became a laboratory for dealing with fear and suffering in films like Nosferatu and The Cabinet Of Dr Caligari.

From the 1950, films, TV and books were all exploring themes of the apocalypse, often in the same way – via science fiction. Memories of genocide, wartime super-weapons like the V2 rocket, and the arrival of the Cold War with its threat of total destruction loomed large in our cultural consciousness.

Cold War fears played out in three ways: via the metaphor of alien invasion in movies like The Day The Earth Stood Still and Invasion Of The Bodysnatchers. In monster movies like Them! and Godzilla (with giant mutated ants and lizards) showing the dangers of nuclear radiation. Through gritty realism in films like Threads or Nevil Shute’s novel On The Beach, about a group of Australians waiting for atomic fallout to hit Melbourne.

Fear humans

Something started to change in the late 1960s, though. In apocalyptic art, the threat of global destruction now started coming from us, ordinary people, not just impersonal war or disease. As we entered the mass media age and live footage of murder, assassination and terror entered every home with a TV, culture picked up on the fact that other people were just as scary as bombs and germs. What greater symbol of humanity’s gift for self-destruction than the ruined Statue of Liberty lying half consumed by sand at the end of Planet Of The Apes? Mad Max took this “fear humans” trope to its commercial peak.

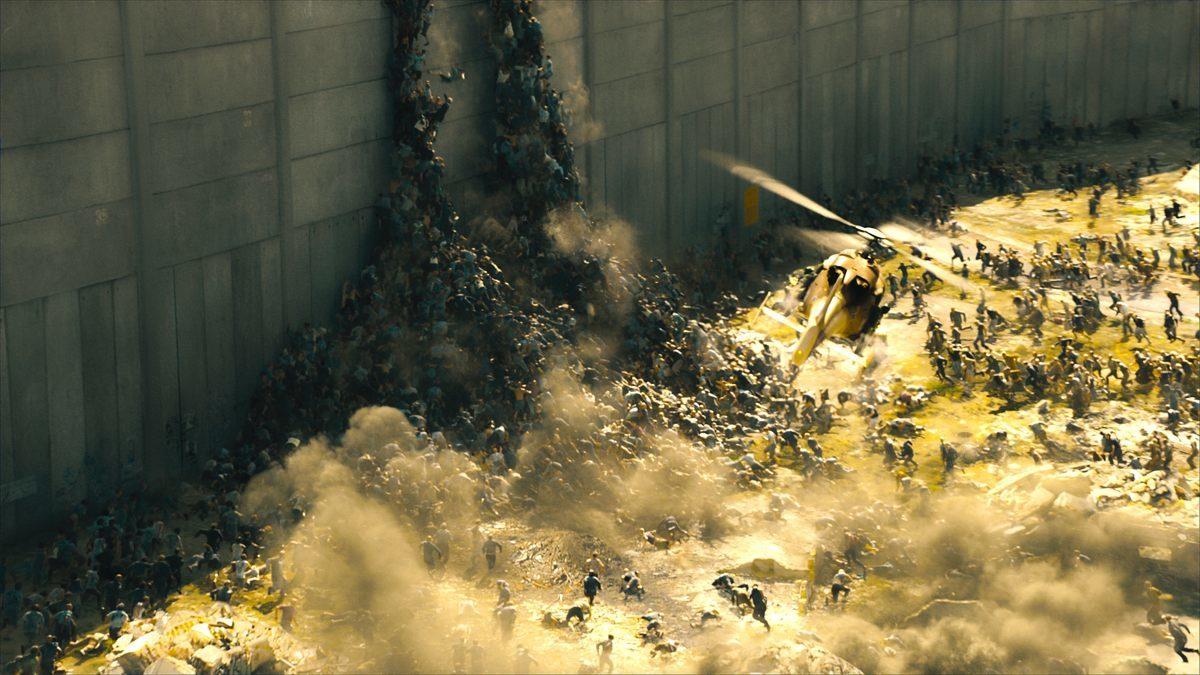

The zombie film came into being in 1968 with George A Romero’s Night Of The Living Dead – since then we’ve been deluged with a genre which is about two things: the end of the world and how it’s other people we need to fear. Ironically, the zombie genre has eaten itself alive with an endless parade of films and TV shows from The Walking Dead to World War Z, and Train To Busan to Stake Land. Its ubiquity has drained its power. A better exploration of the danger posed by other people is found in the 1975 British TV series Survivors.

Literature is now in hock to the post-apocalyptic too. Young adult fiction is dominated by death and disaster with franchises like The Maze Runner and The Hunger Games. Our greatest writers seem compelled to meditate on the end of the world in works like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road and Jose Saramago’s Blindness.

Before the rise of the superhero movie genre (which is itself apocalyptic with the world always on the brink of destruction), blockbusters over the last few decades were dominated by the end of the world. Think of Armageddon, Deep Impact, The Day After Tomorrow, the Terminator series – with their very modern fears of asteroids, climate change, AI and robotics.

Even comedy now embraces the apocalyptic with Shaun Of The Dead, This Is The End, and the TV series Last Man On Earth. Documentaries look increasingly at our penchant for self-destruction in programmes such as An Inconvenient Truth or Life After People. Computer games explore apocalypse and pandemic in titles like The Last Of Us.

You may not think it, but modern music – from punk to pop – is also filled with End Times imagery. REM’s It’s The End Of The World As We Know It; Nena’s Cold War anthem 99 Red Balloons; Einstein A Go-Go by Landscape; OMD’s Enola Gay about the flight crew which dropped the A-bomb on Japan; Eighth Day, Hazel O’Connor’s riff on the rise of the robots; New Orleans Is Sinking by The Tragically Hip, foretelling Hurricane Katrina. The list goes on. Even the most popular, ephemeral and upbeat form of culture is dominated by death and destruction.

What it all proves is that we’ve been dreaming this dream of mass crisis and global panic for a very long time. Now we just happen to be living it. But as everyone from Boccaccio to Otto Dix shows us, we can get through it, we will survive. And once we do get through it, there’ll be a rebirth, a genuine renaissance of art and literature, to explain these strange and sinister times we’re experiencing.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel