WITH fine words and an understandable dash of civic pride, Glasgow's Lord Provost, John Johnston, signalled the start of work on the £6.5 million Kingston Bridge. It was April 28, 1967. One hundred yards away from the heavily-publicised ceremony in Clydeferry Street, however, an unhappy family were sitting tight in their top-floor home, in a partly demolished tenement.

The Watsons – a widower, his son and daughter-in-law, and their four children, aged between four months and five years – were the only remaining family in the only tenement building still standing in the way of the 10-lane approach road to the bridge.

The family had insisted that they wanted a new home in an area of their choosing before they permitted the bulldozers to complete the demolition they had started weeks earlier. The housing department said it had made its "eighth and final" offer to them. A Glasgow Corporation official said he thought that, as a last resort, it would have to eject the family and put the children into care, if necessary.

As the family watched and waited, Mr Johnston declared to his audience of civic leaders and reporters that the city was in the midst of a massive urban renewal that would entail ferocious bulldozing. He sounded a hooter to declare the start of the bridge construction; the man who answered it, Fred Clarke, a pile-driving operator, duly obliged, and revved up the machinery.

The bridge could actually have been a two-tier affair, not a single-tier one. At one stage in the planning process, thought was given to creating a lower tier for service street traffic from Anderson Quay to Springfield Quay, with the upper level forming part of the planned inner ring road. The idea was abandoned after an investigation by the consulting engineers for the construction of the bridge and the Charing Cross section of the inner ring road.

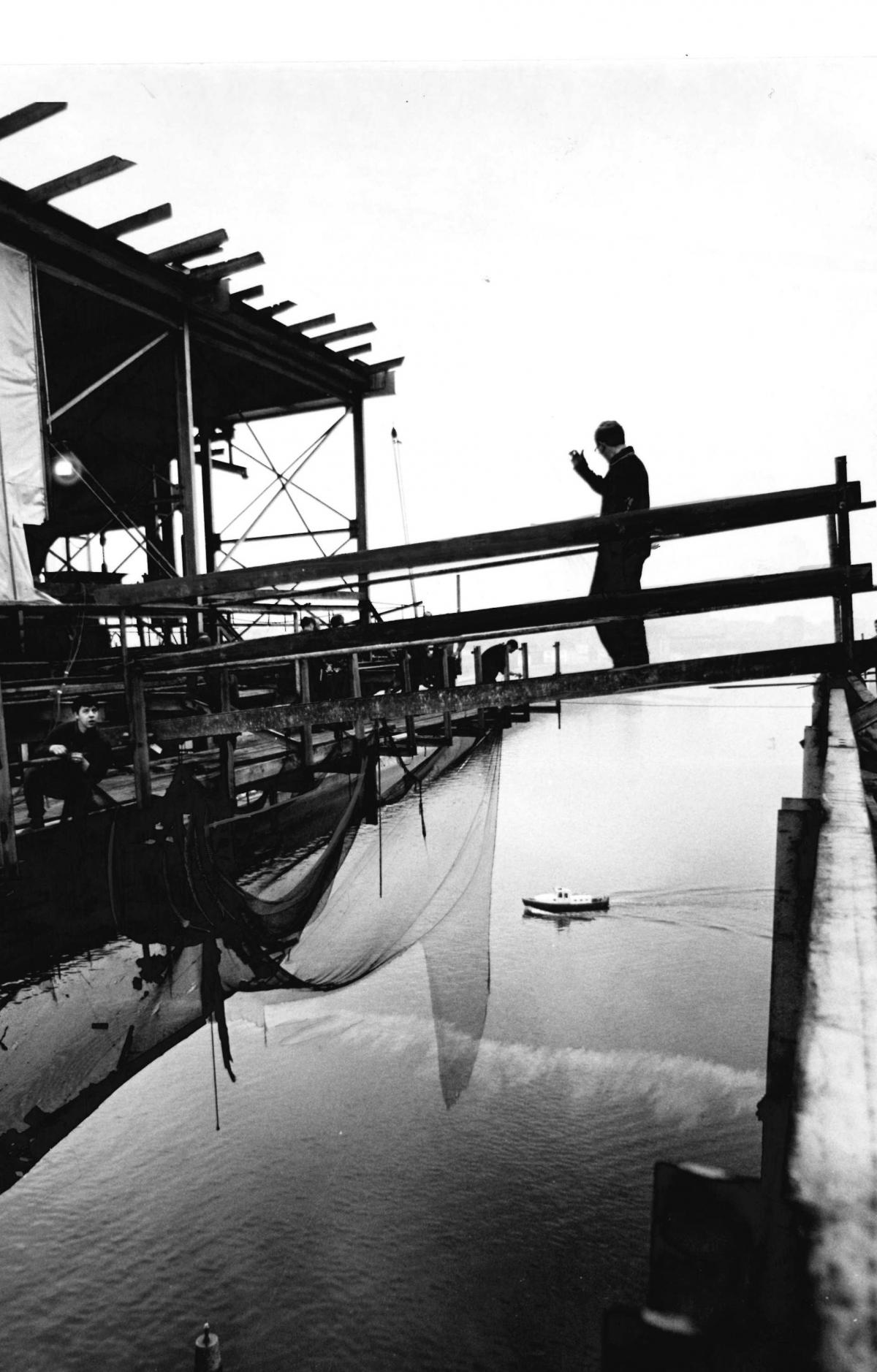

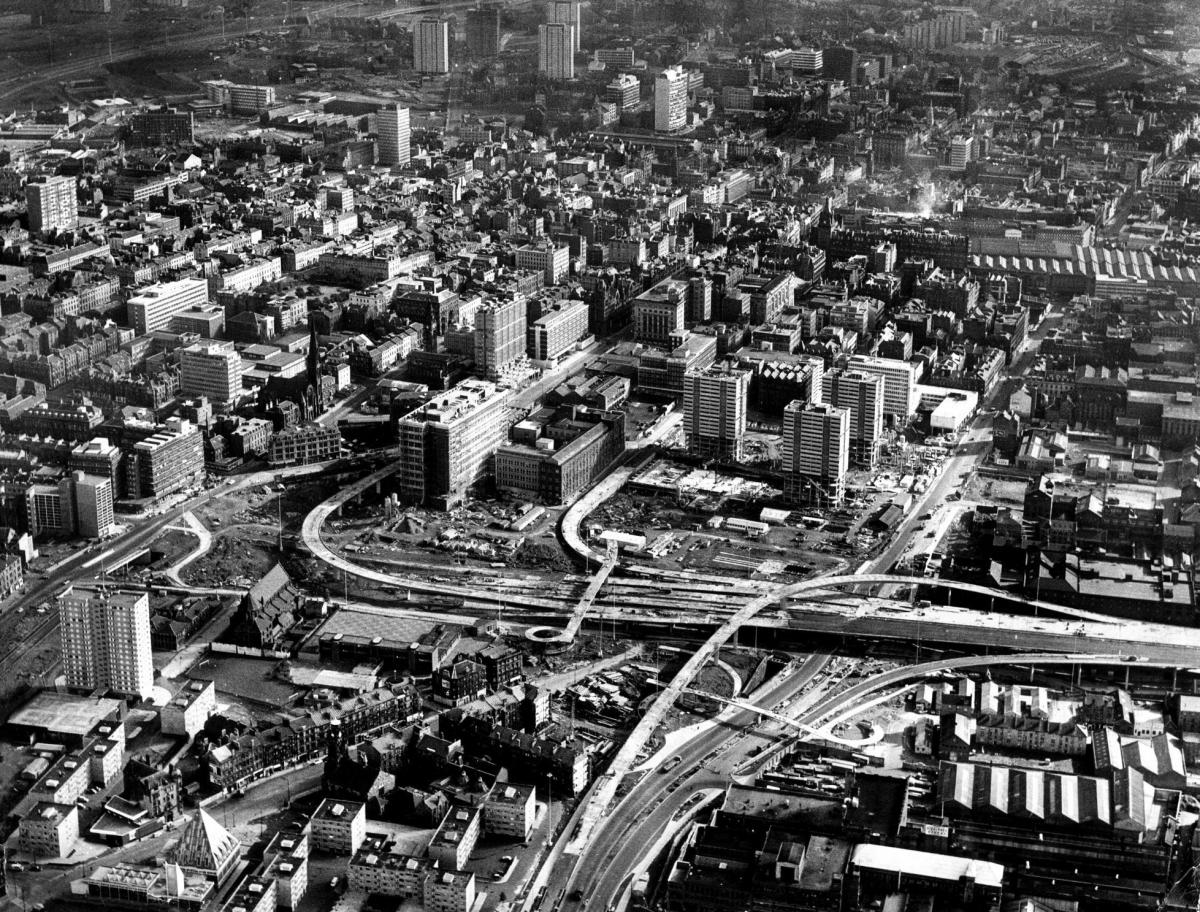

The bridge and its infrastructure slowly took shape over the next three years. There's a vivid aerial shot in the Herald archive, taken in late August, 1969. The bridge and its approach roads and flyovers are still under construction: the actual spans have yet to be added. Construction vehicles and workers dot the rough surfaces of the approach roads. All around them is a profusion of buildings – tenements, and warehouses, and factories – that would, sooner or later, go the way of the Watson family tenement. Today's waterfront bears hardly any relation to the landscape in that picture; apart from the bridge, of course.

By October 1969, there was a gap of just 90ft between the north and south sides of the bridge, and it was closing at the rate of 10ft a week.

The following June, the bridge – a "spectacular half-mile of elegance in concrete", in the words of this newspaper – stood ready to be opened. The cost by then had risen to £11.5 million, including nearly £7 million for construction.

Said the Glasgow Herald on Friday, June 26, the morning of the royal opening: "The bridge ... is the most spectacular link so far in the city's inner ring road. Sweeping 60ft above the navigation channel, the free cantilever, pre-stressed concrete structure is a thing of elegance, even of beauty".

It was the realisation of a "far-sighted" plan drawn up 25 years previously by the late Robert Bruce when he was Glasgow's master of works and city engineer. His proposals, reported to the Corporation in the year the war came to an end, were for an inner ring road, including a new bridge over the Clyde.

The Kingston bridge was the first bridge to be constructed over the river in Glasgow since the King George V bridge was opened in 1928, its aim being to alleviate serious congestion on Glasgow Bridge; the latter had itself been opened in 1899 as the successor to two previous bridges on the site.

The Kingston was in fact two bridges side by side, separated by a gap of 4ft. Each structure was 68ft wide, with a main span across the river of 470ft, and side spans of 205ft each, giving a total bridge length of 880ft.

With twin carriageways each taking five lanes of traffic, the new bridge was at that time the third-largest of its type in the world. The river span of 470ft was the longest example of free construction in free cantilever in Britain.

By 1975, it was reported, the bridge was expected to be carrying 70,000 vehicles a day; by 1990, the total was expected to rise to 120,000. The bridge today remains one of the busiest in Europe; as of a year ago it was dealing with 150,000 vehicles a day.

Before the opening, Davie Campbell, a stonemason, recalled his time on the project. He had stone-faced the retaining walls under the approaches; he had built man-holes on the motorways; he had laid curbstones and setts, and had flagged pavements.

In his own early days in the trade, rough weather had meant slogging on, soaked and cold, until work was impossible – and then he and his colleagues could be laid off without pay. Things weren't too bad now, he said with a smile – there had been a revolution in technique and in working conditions, including a guaranteed week, regardless of the weather. And electric lighting had substantially increased the scope for overtime working.

Opening day was a holiday for Campbell and his workmates, but he had a feeling he would be back to see the ceremony. "You know how women are over royalty", he said. But it wasn't just his wife who was eager to see the opening. After all, when you had put three years of your life into something as colossal as the bridge, you didn't just leave outsiders to open it.

On the big day, councillor William Hunter, convener of the Corporation's highways committee, underscored the importance of the new bridge.

It was, he said, "a vital link in the construction plans to meet the increasing challenge of the rising use of vehicles, to provide the necessary communications for industry in this competitive age, and to form a means of bypassing the city centre".

It was, he added, "a marvellous engineering accomplishment of which we can be proud".

Like Mr Hunter, the Queen Mother went out of her way to acknowledge the disruption that had been caused by the long construction. No project of this kind, she said, could be carried out without disturbance and inconvenience.

"I hope [the residents] will find the settings and the amenities of the bridge so satisfying as to make the noise, dust and disturbance worthwhile, after all".

The opening day witnessed protests by a crowd of young mothers with children in prams. They were protesting at traffic danger on the bridge's approach roads.

They held aloft placards that read 'We want to live', 'Keep our roads safe', 'Must a child be killed?' and 'How many children must be killed?'

"We are not protesting against the Queen Mother", said one woman of 30. "We want to ensure the safety of children, and old people, who have to cross this busy road beside the bridge. There was a fatal accident here only the other day".

Within hours of its opening the Kingston Bridge was proving to be a lure for city motorists.

By nightfall, some 800 vehicles an hour were crossing it, according to the A.A. Police said "everything was running smoothly".

"From our reports", said a spokesman for the R.A.C., "motorists are treating the new motorway bridge with some respect. Many are daunted no doubt by its scale and grandeur".

He had a word of warning, though, for weekend sight-seeing motorists. Any attempt to stop or get out, he said, perhaps with some understatement, would be dangerous.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here