A 17-HOUR road trip from Baghdad to Palmyra across the Syrian desert sounds like quite an adventure for any traveller. Incredibly, this journey was taken by my husband’s grandfather, James McManus, in the 1920s when he lived in Iraq with his wife Kathleen and worked as a civil engineer.

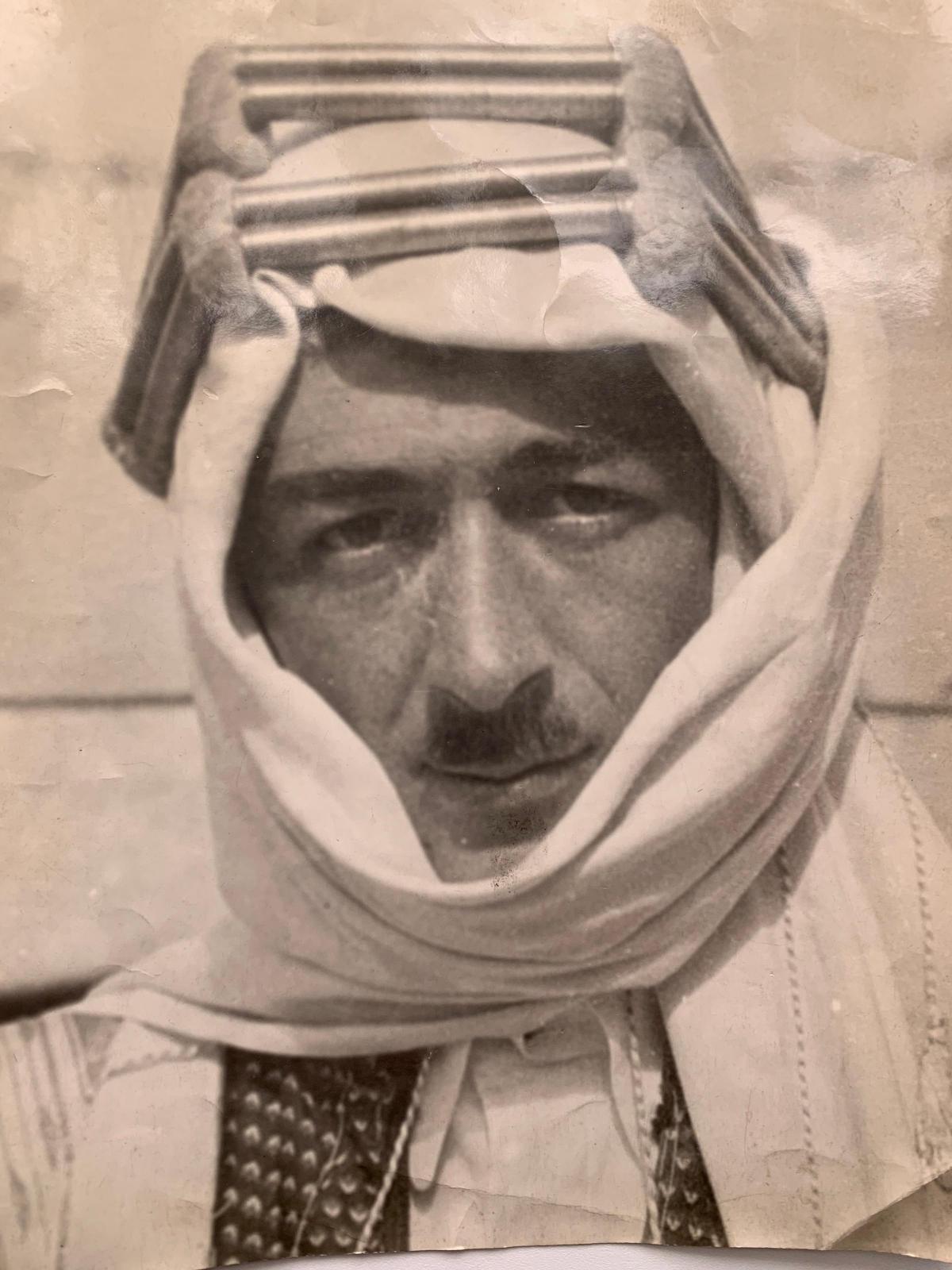

When my mother-in-law Margaret McManus was clearing out a cupboard at home, she found seven pages of yellowing typewritten quarto-sized paper capturing James’s recollections of that trip. He was a keen amateur photographer and tucked inside the pages were six of his photographs of Palmyra, all carefully captioned on the back.

Family treasures uncovered during lockdown don’t come much better than this. James’s words, written in the present tense, are marvellously evocative, capturing the excitement of the journey’s end and the jaw-dropping sight of the ruins dating back to the 1st and 2nd centuries. Reading it now, we feel we’re right there, standing beside him.

Palmyra was devastated in 2015 and 2017 when Isis took control of the area, their systematic attempt to destroy the ancient site was described by the UN as a war crime. Now the Syrian government is working to restore the Unesco World Heritage Site.

These are James’s reflections on the city when he visited nearly 100 years ago.

“Halte, stop. Nouvelle Palmyre.” To the weary and dust-stained traveller approaching Palmyra from the desert, these signs are welcome. Palmyra at last.

Only 17 hours before, the lights of Baghdad, 450 miles away across the Syrian desert, had winked farewell. Powerful touring cars with running boards laden with baggage almost to the height of the hood, travelling all through the night and a great part of the next day, had spanned the barren expanse of desert.

An uneventful journey, it is only when watches indicate that Palmyra should be somewhere on the horizon there is any interest. Every distant mound is the subject of speculation until, at last, the sun on its western course throws into relief a dark irregular shape, which very slowly resolves into patches of light, shade and straight lines recognisable as buildings.

“Palmyra,” says the Syrian driver, “half hour.”

Then on through New Palmyra, a French-Arab town. Turns and twists through the narrow side streets allow occasional glimpses of the ancient city beyond and prepare for what is to come. A sharp turn to the right past a police post and there it lies – Queen Zenobia’s famous city, lonely yet magnificent even in the chaos of its ruins.

The Palmyra of old may have been named the City of Palms but there are few palm trees to be seen nowadays. One sees it only as a veritable city of columns. They cover the area in reckless confusion. Some rear proud heads 40 or 50 feet in the air, as erect as the day they were set up 17 centuries ago. Those upstanding bear marvellously, but precariously, enormous stone blocks, which span from column to column.

Hundreds, alas, lie prone, the weathered yellow stone giving some semblance to huge cornstalks, as if a giant reaper had been at work. Short columns, long columns, columns in their several parts are strewn over the area in rank profusion.

In this barren desert there is no lichen, moss or clinging ivy to cloak or protect the nakedness of the ruins and time has dealt out very uneven treatment. Generally the yellow stones are pitted and scarred by the violent blasts of prevailing sandstorms. In many places, the delicate carvings on the columns are almost as sharp and clear as the day they were cut. While in others, the carvings are completely eroded.

Built into each column is a bracket which originally carried a statue. These were erected to honour those who, braving the perils of the desert, led the wealth-laden caravans safely from India and Persia. Every such successful venture brought wealth and renown to Palmyra and its commemoration in stone also, materially, helped to build the city.

The total number of columns has never been computed, but some indication of Palmyra’s success in trading may be gained from the statement of a French surveyor working on the site that there were 1500 columns in the mile-long Great Colonnade alone.

All over the area stand out isolated groups which possibly, originally, were attached to some public building or perhaps lined some of the minor streets.

Out of all the chaos, stands one orderly array – the Grand Colonnade. Viewed from the Arc de Triomphe, the dangerous state of which is now being remedied by the French authorities, the eye travels from column to column - now upright, now fallen – with the gaps scarcely noticeable from this viewpoint to where, over a mile away, a French military post crowns the highest of the range of hills under the shelter of which Palmyra nestles snugly.

The eye travels back to where, at the foot of the hills and extending into a valley to the left, stand the square-built tomb towers, each of which must have been six or seven storeys high, where the dead of Palmyra were buried. Most of the tiered tombs have collapsed, but above the shroud of mist rising from the sulphurous springs in the valley, some stand out – dead reminders of Palmyra’s living greatness.

Behind and to the left are the ruins of the main public buildings, including the marketplace and the great temple erected to the worship of the Sun God. The same sun which has witnessed all the splendours of the ancient city but now lights only an abandoned stage.

To the thoughtful traveller, the journey of 17 hours across the desert from Baghdad to Palmyra conjures up visions of the old caravan route and brings acute realisation of the reasons for Palmyra’s one-time existence.

The old-time caravans counted the rising and the setting of the sun 21 times before nearing Palmyra. One can visualise them plodding on, and ever on, to the west; the slow, deliberately stepping camels and the jerky, trotting mules laden with bales of valuable merchandise, gold and precious stones. The great silence of the desert broken only by the soft pad, pad of the hoofs and the tinkle of the bells round the animals’ necks.

Day after day, jogging along in the great heat of the desert. Night after night, huddled round the campfire in the shelter of piled-up bales of goods, for the desert nights can be bitterly cold. Day and night, the never-ceasing vigilance to guard against not only the natural dangers of the desert but the possibility of attack by marauding tribes.

One can imagine with what joy the first sight of the Palmyra hills would be welcomed. The anxieties and sleepless watchfulness would soon be over. The dawn of another day would see them safe in the desert city. Then the triumphant procession of the caravan down the long colonnade to the acclamation of the citizens, past the statues in honour of those who had previously accomplished a similar task or perhaps died in the attempt.

These were the men who built up the splendour of Palmyra and brought untold wealth to Queen Zenobia. Her city became the trading centre of the East; her people were the recognised carriers of merchandise between India or Persia and the Mediterranean.

But Zenobia was not content. Her lust for gold and power was insatiable. She sought to throw off the shackles of dependency on Rome and found an empire of her own. For a time, indeed, she did reign as undisputed Queen of the East but the might of the Roman Emperor, Aurelian, ultimately shattered her dreams.

The desert queen was taken captive to Rome where, decked out in wonderful jewels and almost fainting under the weight of the gold chains of captivity, she was led in processions through the streets. Her greed for gold led to her undoing.

So long as Palmyra was in the throes of war, the trade caravans avoided it, seeking and establishing safer routes to the south. This led to the city’s commercial decay and now it stands a lonely, pitiful ruin on a deserted trade route.

The strong light of the sun on the yellow columns turns the whole scene to gold, as if in mockery of the ruins, as the car proceeds towards the gap in the hills which leads to Damascus. Then on through the valley where the silent tomb towers, like ghostly sentinels, watch the traveller depart this city of the dead, while overhead the same sun they worshipped vaunts its eternal existence, emphasising the futility of man and the mercilessness of time.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here