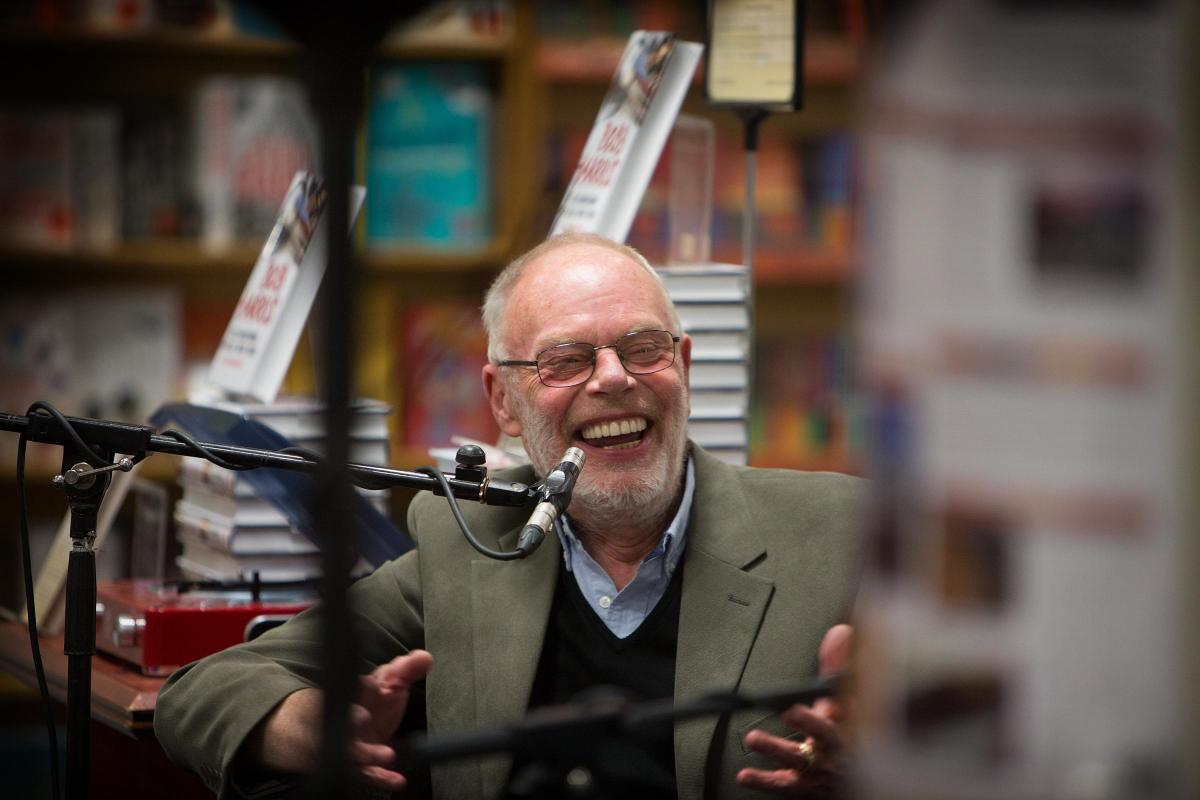

Brian Beacom

FULL disclosure: the man I’ve been interviewing is a very close friend. He is a person I’ve trusted implicitly, taken advice from and hung on pretty much most of his softly-spoken words over a 50-year period (give or take the occasional hiatus).

OK, I’ve never actually met Whispering Bob Harris. But how can you not feel connected to a man who has led you up the stairs to musical heaven, either on his Radio One and Two shows or as the front man for the Old Grey Whistle Test?

How can you not form a tight bond with the man who introduced you to the classiest singer songwriters, (from Neil Young to the young Elton and Jackson Browne) a man who then sells you country, with a passion so powerful you’d reckon one of the four mothers of his eight children would be called Tammy or Shania, and at least one of the kids would have a hyphen in their first name?

Yet, despite Bob and me being tighter than a junior rodeo rider’s grip, there’s so much of the 74-year-old I’m keen to discover. I want to know about his relationship with the music gods such as David Bowie and Elton and Robert Plant. Did he ever get too close and be burned by disappointment?

And how did he deal with the pressures of fame, being lauded by, and then attacked by the media? How did he come to terms with being attacked literally by a group of crazed punks, led by (soon to be dead) Sex Pistol Sid Vicious?

But I also want to know if his life has been as calm as he looks. Surely that just-back-from-Woodstock-whistling-a-CSN&Y-tune countenance must have been forced at times?

I want to know how he has managed to be on remain at the top with his Radio 2 show, celebrating 50 years in broadcasting, given the more mature male broadcaster is on the endangered species list.

To begin, we talk about his return to his smashing country show. Is part of the success down to the similarities with the early 1970s? Can I hear elements of Poco, Little Feat, Steely Dan and the Eagles bleed into the 'new country' for which he is now a poster boy?

“You are amazing for spotting that,” he says in warm voice, confirming my belief we truly are chums. “It is absolutely true. Whistle Test was surrounded by singer-songwriters. It was the time of Neil Young and Harvest, which was recorded in Nashville, of Gram Parsons and Emmy Lou Harris. That form of music lives on.”

It certainly does. But here’s a thought, Bob. Country music tropes feature straying lovers, booze and beat-up guitars. And dogs. Not young, middle-class boys who move from trainee policeman to land the greatest job in music as the Whistle Test frontman.

How does a teenage beat cop from a sleepy Northampton village become besties with Zeppelin’s Robert Plant and come to get on “like a house on fire” with John Lennon? “Well, my dad was a policeman,” he explains, “and he worked on a quiet village beat and was keen for me to join the police. So I did a deal with him that I’d give it my best shot as a cadet until my 19th birthday – and if it wasn’t for me he’d back me 100 per cent in whatever I wanted to do. And that’s exactly what happened.”

Just as well young Harris upped and offed to London. The nickname ‘Bob the Bobby’ would not have been cool. But the move was never in doubt, my chum explains.

Harris had loved music since he first found Radio Luxembourg on the dial, reflected in the excitement he felt in 1957 when he bought his first 78 rpm disc, Paul Anka’s Diana (which he still has.)

And so, in 1966, when London was officially declared “The swinging city,” by Time Magazine, young Robert Brinley Joseph Harris swung into town, with the dream of breaking into music journalism. “It took the best part of four years,” he rewinds, revealing a stoicism that’s essential for survival – and longevity. “I had no money, I was lonely, and I had a little room in a bedsit.”

Yet, there were huge positives to the move to Bedsitland. “I was surrounded by creativity,” he says, his voice revealing the excitement of the day. “It was the counter-culture period, which saw the opening of new magazines, bookshops, almost every day.”

Harris landed a job with Unit, a small contemporary arts magazine and one of the young man’s first interviews in 1967 was with Radio One DJ John Peel. It turned out to be life changing. “In the room at the time was a curly-haired, elfin musician named Marc Bolan. I became friends with both.

“But John really took me under his wing and shepherded me in the direction of Radio One. It was an incredible experience and to find myself there was where I wanted to be. And when Marc found success in 1971 I compered his first major T-Rex tour. From that friendship I came to meet David [Bowie].”

Meantime, Harris also co-founded Time Out magazine. And he found a new friend in the form of a shy record shop assistant named Reg. The shop boy agreed to display copies of Harris’s publication in return for a review of his new album, Empty Sky. And so it was that Elton and Bob became great friends.

In 1972, Bob Harris’ loon-pants-covered backside found itself sitting on the most important stool in the music business. But did working on Whistle Test (the title came from a song-publishing legend that if the doorman – ‘the Old Grey’ – could whistle your tune, then it passed the popularity test) and Radio One ever become problematical in that his closeness with the talent meant tough choices?

“Yes, I put a lot of pressure on myself at the time, trying to remain loyal to the artist,” he admits. “But, for example, if a country star crosses into pop music, I really can’t play that music.”

Did that apply when David Bowie descended into his Low period? “Well, there comes a point in superstardom that you do tend to disconnect from friendships anyway,” he says in slightly sad voice. “David and I were very good friends through the late 1960s and early 70s. It was much the same with Marc. But from the fame onset none of us really got to see much of him.”

And Elton? “No, because Elton pops back into my life every now and again. He appeared on my This Is Your Life a few years back. Like Brian May, of Queen, I think of him as always being in my life. We don’t see each other all the time but we’re always in touch.”

He smiles. “It’s lovely when an artist acknowledges the support you’ve given them.” And does it hurt when acknowledgement doesn’t appear? “The thing to do is not to expect it. You see, fame brings with it a pressure that takes you away from the places you have been before. And that certainly happened with David.”

It also happened with Bob Harris. He became a de facto rock star, touring the States, fronting concerts for the likes of Led Zeppelin, interviewing stars such as Springsteen and John Lennon.

To the point he lost the plot? “I think so, yes,” he says, in soft but emphatic voice. “It’s almost an inevitable consequence of the huge amounts of attention on you. It’s hard now to imagine the impact that Whistle Test had but I did lose my way for two or three years.” He sighs. “It can swamp you.”

The first feature of the collateral damage was his relationships. He split with his wife, Sue. “We’d become such good friends with Marc Bolan and his wife, June, for example. We had a nice life. But Sue didn’t enjoy the fame side of things and I’d be off to America for weeks on end, staying out really late, being driven around in limos, living the crazy lifestyle of the rock stars that we were promoting while Sue was at home bringing up our two girls.”

His mentor and close friend John Peel was so appalled at Harris’s apparent neglect of family for work that he did not speak to him for almost 20 years.

But there were other problems with playing the role of rock star. Harris contracted a form of Legionnaires’ Disease and spent four days in a coma. He put part of the near-death experience down to the lifestyle he had been living.

The Icarus fable continued to feature in his life. By the late 1970s the era of furry waistcoats, tie-dyed T-shirts, bell bottoms and summer-of-love outlook was long gone. The new face of music arrived with a sneer instead of a smile and an angry safety pin through its nose.

Whispering Bob was silenced, the OGWT stool going to pseudo-punk Anne Nightingale. And then came the attacks, in print, from the likes of the Melody Maker. In 1972 one writer praised Harris to the roof. Six years later the same writer described the music presenter as ‘undeniably the most reviled personality both on television and within rock music.’

Bit harsh, Bob? “It’s a cliché that the press builds you up and knocks you down, but it did happen. What was thrown at me was particularly vicious and personal. I became a coconut shy, a figurehead for the bile.”

Harris is more sanguine now. “I had a publicist in the mid-70s, and we agreed I would do interviews and expose myself. So I couldn’t really have too many complaints.”

The attacks weren’t confined to print. One night in a club, Harris was attacked by Sex Pistol Sid Vicious. The one-time hippy avoided the haymaker and was pulled to safety by Procol Harum roadies, but bottles and glasses were thrown – and Harris’s friend was badly beaten.

Whispering Bob knew the writing was on the blood-splattered wall. Here was a broadcaster “laid back to the point of narcolepsy” working in a music industry that was all about frantic energy. But there was another reason to step back out of the limelight. “I’d lost my identity to television,” he said in one interview.

He had already lost his Radio One show, due to cuts. As a result, the 1980s became Bob Harris’s lost years, a decade spent in local radio. When he had almost died during the Legionnaires illness, Harris remembers seeing ‘a long tunnel of light.’ Now there was no tunnel, and very little light.

But he kept going. He married again, to Val, a TV chef and a writer and in 1989 the radio whisperer returned to Radio One, after a 10-year absence. The second marriage didn’t last but in the early 1990s Harris married for the third time to Trudie, who became his manager and the mother of three children.

The needle lifted again from his career in 1993 when controller Matthew Bannister launched a “cull” of the older Radio One DJs. (Harris was pulling in 19m at the time.) “We’ve remained friends, as amazing as that sounds.”

That indicates my chum is a measured man, not a grudge bearer. Good for the soul. And the career. After a three-year sojourn into local radio, Harris got the call to come back to Radio 2 – and he’s been there since.

Yet, does he consider himself fortunate given the BBC’s positive discrimination policy, pushing female talent forward? “I can remember talking recently about the great DJs who emerged from pirate radio, Tony Blackburn, Kenny Everett, Johnnie Walker . . . and there wasn’t one woman. Obviously, it was a different time, but you need a balance.

“The BBC is introducing huge budgets into diversity and that reflects the times. It should be happening.”

But you also need to pull in an audience, Bob. Rajar figures revealed Zoe Ball has lost a million a week? “Well, I’m never been caught up in the idea the BBC should all be about figures,” he argues gently, still not looking to upset our friendship. “At the time of Whistle Test, the likes of Monty Python and Late Night Line-up were freeform, blue sky-thinking programmes that weren’t restricted. The BBC should always be about the diversity of ideas.”

Harris also adds that Auntie hasn’t thrown all the old babies out with the bathwater. She still talcs the backsides of himself, Johnnie Walker, Tony Blackburn and Paul Gambaccini, 1970s star-names who will never see 70 again.

When Bob Harris speaks of his (our) chums you sense a real loyalty. He’s certainly shown loyalty to Danny Baker. Pre-Covid, the pair had planned to tour together, telling tales from their lives to theatre audiences up and down the country.

It’s a great idea. But did the idea of working with Baker prompt a fear of guilt by association, given Baker’s 2019 gaffe in posting the infamous chimp/Royal baby pic which resulted in accusations of racism? “No, none whatsoever,” he says emphatically. “I love Danny. We’ve been friends for years. He’s controversial from time to time but he’s absolutely not a racist.”

As well as being loyal (another reason why Bob Harris has survived in the business) there’s an innate toughness. In 2007 he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. Along the way he managed his way through the bankruptcy he endured when he fell foul of the property crash. Last year he survived an aortic rupture.

What you sense is that Bob Harris is like vinyl. He has real substance and he’s never really gone away. But what comes across is his passion for music, for life and family and work. He can’t wait to get back on the road next year with Danny Baker, for example.

Robert Plant has already said he’d like to “come out on some of the dates.” Such is Bob Harris’s pull, who knows? Could Elton, or Taylor Swift, or Mick Jagger make an appearance? “We’ve had friends of ours saying they’d like to pop in on the night,” he says with a teasing smile. “It is an amazing thing,” he says slightly coyly. But that’s OK. Bob Harris is my close friend and friends can be a bit coy to each other, can’t they?

Bob Harris marks 50 years of broadcasting in Bob and Greg (9-10pm, tonight) and presents The Country Show every week (Thursdays, 9-10pm) on BBC Radio 2

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel