By Professor David Wilson

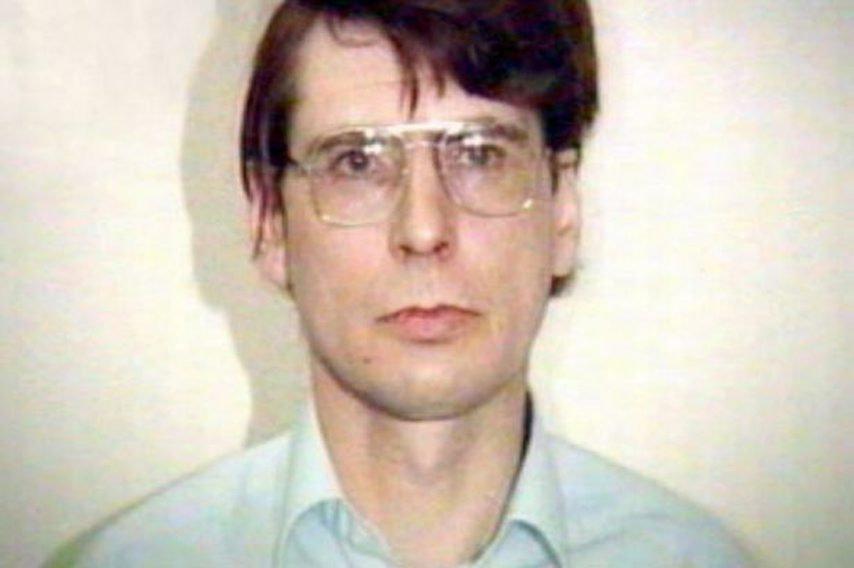

I FIRST met Dennis Nilsen shortly after his conviction on six counts of murder in November 1983 and his transfer to HMP Wormwood Scrubs the following day, where I was working as an assistant governor, and last encountered him in early 2018 when someone claiming to be “Dennis Nilsen” followed me on Twitter.

I had to call the governor of HMP Full Sutton, where Nilsen would die a few months later, to query whether one of our most notorious serial killers had managed to smuggle a mobile phone into the jail and was now communicating through social media.

In between these bookends, I met him another few times when I was still working in the prison service and, after I had left, he wrote to me on many occasions. I have at least 600 pages of A4 of his writings that he sent to me, with titles such as Orientation in Me: A Trick of the Light and Brain Damage: The Missing Element.

The title of this latter document would seem to suggest he was struggling to try to work out for himself why it was he killed so many young men – the actual number is still a matter of some controversy (six, 12 or 15?) – although don’t be fooled.

Most of what he wrote is simply bad pornography and the steamy fantasies of a gay man who wanted to be seen as masculine, powerful and controlling of the men who came into his life. He wasn’t really interested in discovering what it was that drove him to commit murder, but merely wanted to control those people – like me – who were attempting to suggest an explanation for why he had wanted to repeatedly kill. Nilsen didn’t like that.

He wanted to keep control of any theorising, whether by his perceptive biographer Brian Masters who had suggested he had “killed for company”, or by the psychiatrists at his trial who had discussed his lack of emotional development, narcissism, his stunted sexual progress, alcohol abuse, and various other clinical aspects of his personality.

I had discussed with him the nature of evil and those age-old questions about nature or nurture, free will and determinism and whether he was born with a predisposition to kill, or if the circumstances of his childhood and the relationships that he had developed at that time had laid the foundations for his becoming a murderer.

READ MORE: Eight chilling facts about Scottish serial killer Dennis Nilsen

Over time I came to realise that, while all of this theorising about Nilsen as an individual might indeed eventually help us to better understand what he had done, there were other broader issues we also needed to consider. Why, for example, had he chosen the Army and the Metropolitan Police as careers, with their disciplined and disciplinary functions, and how had these professions come to aid him as a killer? What had come first – the desire to kill or the choice of profession?

This link between occupational choice and serial murder becomes even more obvious when we remember that many of our most prolific serial murderers had jobs as lorry drivers or delivery men and that these professions gave them an opportunity to roam the country searching for suitable victims, and also the ability to cross police force boundary areas to dispose of the bodies of those they had killed.

We now describe these killers as “geographically transient”, as opposed to “geographically stable”, and that geographic mobility allows a murderer to keep killing because it is much more difficult to link similar cases if they are committed in different parts of the country.

Nilsen was geographically stable – he killed in north London at a flat in Melrose Avenue, where he had access to a back garden, and Cranley Gardens where he lived in the top-floor flat of a house that was shared with other tenants.

The lack of a garden was to prove decisive in bringing his killing cycle to an end. He would pick his victims up at local pubs and then bring them back to his flat with the promise of more alcohol, and a warm place to sleep for the evening. Both were tempting prospects for many of the homeless men whom he targeted.

So how was he able to get away with repeatedly killing in such a small geographic area? The answer to this question is again about broader, structural issues rather than simply the individual responsibility of Nilsen. As a number of victims who survived one of Nilsen’s attacks have suggested, when they reported the matter to the police they simply refused to take them seriously and one or two, such as Douglas Stewart, have suggested this was due to homophobia.

As Douglas was later to explain, after he took a police officer round to the flat where Nilsen had attempted to throttle him, Nilsen explained everything away as a “lover’s quarrel” and, “as soon as the word ‘homosexual’ was mentioned the police lost all interest”.

We can even see how Nilsen was eventually caught, by a Dyno-Rod engineer called Michael Cattran who was responding to plumbing complaints by Nilsen’s neighbours (Nilsen was disposing of body parts down the toilet and this blocked the drains), as indicative of a lack of police attention to the complaints raised by Douglas and at least one of the families of some of Nilsen’s other victims.

READ MORE: Bloody Scotland: The 20 crime writers you need to see at this year's festival

Perhaps, given this alleged lack of police interest, it should come as no surprise that gay men are regularly the targets of British serial killers and, quite apart from Nilsen, the 1980s saw such killers as Colin Ireland and Michael Lupo also target gay men, and our most recent serial killer is Stephen Port, who is responsible for murdering at least four gay men and was given a “whole life tariff” in November 2016. In other words, homophobia persists, despite the very different worlds occupied by Nilsen and Port.

Nor should we ignore the fact that Nilsen regularly targeted the homeless. His victims, whom he once described in his writings as “my tragic products”, were people who would not be missed when they eventually disappeared. They easily slipped through the cracks in the fabric of our society so that no-one really bothered, or questioned what had happened to them; no-one advocated on their behalf and some might even have seen their disappearance as something to be welcomed.

I worry that we might take comfort from imagining that “it isn’t like that today” but 726 homeless people died in England and Wales in 2018 – a 22% increase on the previous year’s figures. I have no doubt that some of those deaths were related to underlying health problems associated with homelessness, and with drug and alcohol abuse, but who’s to say that a serial killer isn’t also targeting this group of people as victims? Would we notice their disappearance? Would we care?

Nilsen was different to the other serial killers I have met or worked with in that he talked endlessly about the murders he had committed. Most serial killers avoid discussing what they have done and, certainly in my experience, never engage in discussing why they turned to murder – most are what I have described as “silent and uncommunicative”. In that respect Nilsen was different, although I never really believed anything he said as to what it was that had made him into a serial killer.

Part of my reluctance to accept what he claimed was that he would talk at me, rather than with me. I was often merely a prop for him to have a conversation with himself and was only occasionally allowed – or expected – to ask a question.

That was how controlling Nilsen liked to be, and I came to realise he worried that if he let down his guard for even a few seconds it might expose him to some blunt truths about what he had done and who he was. Those truths could be avoided if he just controlled who it was who was doing the talking and, therefore, what was being said. He could give the appearance of wanting to discuss his serial murders, whilst all the time subtly, and sometimes not so subtly, refusing to let anyone else get a word in edgeways.

READ MORE: Eight chilling facts about Scottish serial killer Dennis Nilsen

His long-windedness might have given the impression he wanted to talk but it was all an act, for his goal was to silence discussion, in much the same way he throttled his victims. They, too, were mere props for his narcissistic, controlling and murderous personality.

Signs of Murder by Professor David Wilson is published by Sphere, priced £20

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel