Rory MacLean

We all like a good story. We all need a narrative for our lives. The most potent stories give us an idea or individual to believe in, as well as someone to blame when things go wrong: Stalin loved little children, Jews caused Germany’s ills, Middle East migrants bring cholera into Europe, Brussels stripped the UK of its independence. Today many Russians have come to fancy that there was a golden age that can be reclaimed, that the whole Soviet people once marched in step on Red Square on May Day, calling out in a single voice ‘Glory! Glory to the victorious people!’

On the outskirts of Moscow a dozen hulking T-90 battle tanks shook the earth, rent the air and caused a child to drop her banana ice-cream cone. A rank of spanking new T-14 Armatas, the world’s most deadly tracked combat vehicle, pushed into the column. Atop each turret stood a Russian tankman: proud, defiant and gazing ahead to victory, as well as at the unmarked pedestrian crossing. Spectators darted between the raucous killing machines, videoing them through the billows of diesel exhaust. Ground Forces soldiers in full battle kit jogged alongside them, and around a young mother jerking a pram through the track ruts. All year round Patriot Park, Russia’s military Disneyland, welcomes visitors for a day of ‘family fun’ but – over one weekend in September – it’s the venue for the annual Army Show.

My young guide Anna and I took our seats in a grandstand packed with excited merry-makers: decorated veterans in waterproof shells, toddlers holding red and blue balloons, teenage girls wearing short summer dresses and souvenir army caps set at jaunty angles. When Vladimir Putin opened the 13,300-acre park, he’d called it ‘an important element in our system of military-patriotic work with young people’. He’d also used the occasion to announce the addition of 40 advanced ballistic missiles to the nuclear arsenal.

I was spellbound, bewitched and deafened as Anna talked about growing up in Moscow, and her father’s untimely death, until martial music and black exhaust cut across our conversation. ‘The March of Soviet Tankmen’ spewed into the air, filling it with boasts of courageous men and invincible armour. A column of fighting vehicles thundered past us at full speed, a T-80 turned on a rouble and a BTR-80 armoured personnel carrier released a squad of infantrymen. Next a Smerch multiple rocket launcher took aim at a distant target, erupting with an ear-splitting roar, I realised it wasn’t only my senses that were explosive. Live ammunition was fired at the annual show. Two TOS-1 heavy flamethrowers followed, blazing an arc of fire across our field of vision, and then a vicious Buk-M2 that could – according to my programme – ‘perform multiple missions with greater mobility and simultaneously engage a maximum of 24 targets’. In 2014 a similar Buk, with five-metre-long SA-11 guided missile, had brought down Malaysia Airlines flight MH17, killing all 298 passengers and crew.

‘Thundering with fire, glinting with steel...’ enthused another patriotic song as a phalanx of Mi-35 Hind helicopter gunships appeared above our heads and paratroopers sailed down to the ground, forming up to advance swiftly on an imagined enemy. On the field, television cameramen darted between the machines, moved in for close-ups, then set up for the ‘tank ballet’ where Bolshoi dancers pirouetted around a ring of T-80s. Their video feed was projected onto both huge screens around the park and the national network.

In the first years after the collapse of communism, Russia’s gross domestic product had fallen by half, more than America’s during the Great Depression. Bank savings had been wiped out by inflation. Free health care ceased to exist. Male life expectancy crashed to 57 years, the lowest level in the industrial world. As ordinary people struggled to survive, they began to long for their Soviet past. Their nostalgia was manipulated – by the government and its compliant media – to perpetrate the myth that enemies surrounded Russia. If the nation stood up against them, Russia could be great, again.

Over a bucket of Robopop popcorn, Anna told me, ‘We must defend ourselves against NATO aggression and other terrorists.’

‘Terrorists?’ I asked.

‘Like those who killed my father.’

Twenty years ago some 400 kilograms of explosives were detonated on the ground floor of her family’s apartment building in south-east Moscow. The nine-storey block collapsed, killing and injuring hundreds in a horror of flying glass and crumbled concrete. A charmless and little-known bureaucrat – a former FSB head, successor of the KGB – then stepped forward to announce to the traumatised nation that the perpetrators were terrorists who had been trained in Chechnya. ‘We will pursue the terrorists everywhere,’ he declared at a news conference. ‘If they are in an airport, then in an airport and, forgive me, if we catch them in the toilet, then we’ll mochit them – rub them out – in the toilet.’

No matter that the Chechens insisted that they had nothing to do with the bombings. Overnight the Russian people had an enemy on which to focus their anger, and the popularity of the charmless bureaucrat – whose name was Vladimir Putin – soared in the wake of his televised revenge attack on Chechnya. Three months later he stood in the country’s presidential election, and won.

Until that time, politicians and oligarchs alike had been hated for their pillage of the country. For them to survive, faith had to be restored in the regime. Many Kremlin-watchers believe that the FSB was instructed to make people afraid. One of its vehicles and two employees – both of whom later died in mysterious circumstances – were caught transporting sacks of explosives to the cellar of another target, in the city of Ryazan south-east of Moscow. In addition, RDX hexogen, the key ingredient in the bombs was held in facilities under the exclusive control of the FSB.

‘What? Blow up our own apartment buildings? You know, that is really ... utter nonsense! It’s totally insane,’ said Putin when the facts came out, and in response to accusations of complicity. ‘No one in the Russian Special Services would be capable of such a crime against his own people.’

Then he shut down the public enquiry.

At Patriot Park I told Anna that in that fatal year the die had been cast for her country’s future. The Russian apartment bombings had been the greatest political provocation on the continent since the burning of the Reichstag. It was an event – a conscious and decisive act – that obsessed me, both because of its iniquity and because of how much it had changed Europe.

When I’d finished talking, Anna stared at me. She seemed unable to grasp my meaning as if I’d been speaking in tongues. She tossed her plait over her shoulder and said, ‘This is not true.’

Overhead the Swifts and Falcons aerobatic teams – flying MiG- 29s and Sukhoi Su-30 fighter bombers – laid red, white and blue smoke trails across the sky, their loops, barrel rolls and fly-pasts accompanied by heavy rock music.

‘Welcome our pilots!’ commanded the announcer, calling out the names of the high-flying airmen. ‘Welcome Team Commander Viktor Selutin! Wingman Ivan Osyaikin! Master Pilot Sergey Vasiliev! Applaud louder, people, so they can hear you!’

The aircraft climbed and stalled, released dazzling magnesium flares, tumbled towards the ground and then relit their engines to dive at the ecstatic, awestruck crowd. People stood on their chairs, applauding the spectacle. In the grand finale the audience touched their hearts for the national anthem.

At the end of the show we walked away through a haze of jet fumes, along a corridor of sparkly red plastic stars, pausing at an historical display of ‘captured’ Second World War German armour (all the German vehicles were replicas, newly made in Russian factories as there are no longer enough originals to go round the country’s many patriotic events). At Patriot Park, as elsewhere in Russia, the victory over Nazism is sacred. Why? Because after the gulags, after the economic failure, after the humiliation of millions under the Soviet system, it is the one achievement of which all Russians can be proud.

‘We can do it again!’ read a young man’s baseball cap, the jingoistic catchphrase printed beneath the hammer and sickle that perpetrated – as it did on every military vehicle in the park – the glorious memory of the Great Patriotic War.

Anna and I pushed through the crowds at the Berlin Reichstag replica, built for Yunarmiya ‘young army’ cadets to practise their assault techniques, and reached a vast central courtyard the size of two football pitches. Children clambered over hundreds of ultramodern tanks, artillery pieces and Terminator fire-support combat vehicles. Grandparents struck poses at the controls of huge S-400 Triumph anti-aircraft missile launchers. Salesmen from Arsenal Arms Industries and UVZ Uralvagonzavod demonstrated armed drones and Balkan grenade launchers. At the Kalashnikov range, one of 29 shooting galleries on the site, thrill-seekers queued to test the new AK-74M assault gun (live ammunition is issued only to Russian passport holders).

Anna told me, ‘Patriot Park makes me proud to be Russian.’

When the Soviet flag had been lowered for the last time, it took with it the illusion of a people’s Utopia. The seductive dream that had shaped the country was exposed as a deception and Russians found themselves with no ideology to cling to, and no vision for the future. Into the vacuum was poured the nostalgic ‘feel good’ propaganda, which worked simply because people needed something to believe. Russians were in trauma, their collective memory racked by historical suffering and guilt. There was no appetite for the Freudian idea – which had so transformed Germany after the Second World War – that the repressed (or at least unspoken) will fester like a canker until it is brought to light.

Hence in Russia there were no Nuremberg trials. No one accepted responsibility for loading innocents into cattle trucks, for lifting a rifle in a firing squad, for snitching on a neighbour to save one’s own skin. No one admitted that Stalin had killed more Russians than any foreign invader. Any idea of collective repentance vanished.

Instead, in their need for a new identity, Russians embraced the mythologised version of history: deifying Stalin, welcoming the restoration of the Soviet national anthem, printing school textbooks that glorified the Red Army and condemned its withdrawal from Germany as a ‘fatal mistake’. They accepted – or at least considered possible – untruths such as the idea that it was Mikhail Gorbachev who destroyed the Soviet Union, that Ukrainian nationalists crucified ethnic Russian children and Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 had been pre-loaded with ‘rotting corpses’ in Amsterdam. Their sense of belonging was restored by old blood-and-soil nationalism.

In Soviet times, survival had meant lying. Only by spouting dogma could someone excel at school, win a place at university or secure a good job. Ideology was used, not believed. The regime itself had to lie to survive, falsifying the past, pretending that no honest citizen needed to fear it. Its leaders trumpeted about serving the people, then shook up the political order to retain their grip on power. Now many Russians – as many Westerners – have lost their appetite for the truth. They choose not to ask questions, preferring the easy choice of falsehood, of being fed simplistic solutions to complicated problems, of championing leaders who have the power to reshape reality in line with their stories. The lies have become the glue that holds people together.

To kick off the afternoon’s entertainment, balaclava-wearing dancers in Spetsnaz SAS uniforms performed a robot ballet on the main stage. Families checked out riot-control vehicles and inflatable, full-size MiG decoys, useful to confuse enemies at times when deceit alone won’t do. In the souvenir shop knick-knack hunters bought Putin fridge magnets and bomber jackets adorned with the word ‘Victory’. A baby’s cot in the form of a Buk missile launcher was among the weekend’s specials. Nearby a child ate a hot dog beside an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capable of destroying an entire country.

Anna’s absence of doubt had disturbed me, and a sudden wave of anger washed over me. I asked myself if she might argue that a strong leader had a duty to wield power, even to commit crimes, for the good of the nation. Yet she never questioned that her father had been taken by anyone other than ‘terrorists’. Russia’s leader had said it was so, and he was too exemplary, too powerful, to be doubted. She gobbled up his dezinformatsiya as truth, as our own disingenuous operators – unprincipled politicians, virtual disruptors and digital kleptocracies – have learned to do to manipulate our behaviour, to shape us.

We parted at the centre of the park beneath a statue of Georgy Zhukov, the Red Army commander who had captured Berlin in 1945. A simple inscription appeared on the plinth, but not Zhukov’s name. The deliberate omission of his name transformed the statue’s meaning. It was a code that every Russian understood. ‘To the Marshal of the Victory’ did not refer to Zhukov, but rather to Stalin ... and by extension to the once little-known bureaucrat who’d unveiled the statue a few years earlier.

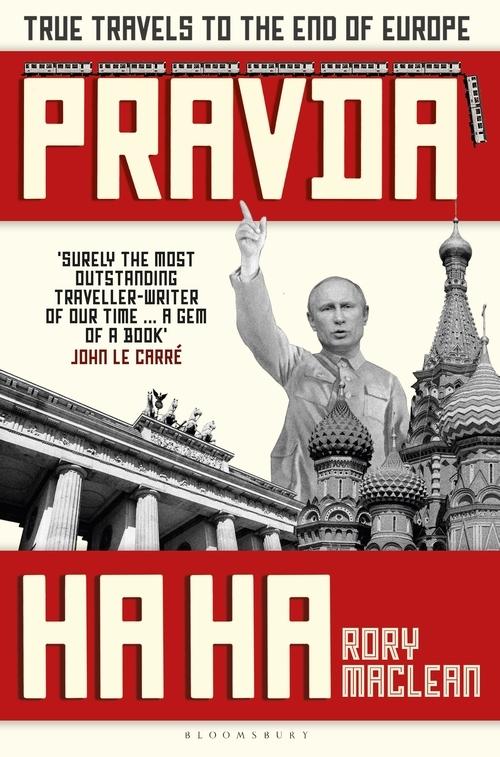

Rory MacLean’s latest book Pravda Ha Ha: Truth, Lies and the End of Europe is published by Bloomsbury this month. Buy it here

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here