AUTUMN, 2020. We’re all still in a world between lockdown and lockdown. A lot of us are angry. Perhaps our tendency towards outrage has been exacerbated by circumstance – there’s a lot to be outraged about. But it may also be that, at a time when many of us have found extraordinary solace in the natural world, we’ve become newly aware of its fragility and of the wilful damage our fellow humans continue to cause to other species and to the earth itself. That may be why it’s not surprising that there should have been a furious response to three recent news stories, all featuring the same unlikely subject – Lagopus lagopus – grouse.

First was the Prime Minister’s clumsy announcement that grouse shooting should be excluded from the Covid-limiting rules by which most of us are living. The second featured Channel 4’s showing of the illegal trapping and killing of a protected goshawk by a gamekeeper on a Yorkshire grouse moor. Third was the public announcement that what was concealed in the small lead packet found in a Perthshire river earlier in the year, was the satellite tag of a golden eagle who disappeared from a grouse moor in Scotland in 2016.

There’s something of the moment, something important about these stories. Of the three, the one which has aroused most anger is the Government’s exemption for grouse shooting. Despite the almost impossibility of maintaining social distancing and safe practice during the travel to shoots and the socialising which is so much part of ‘game’ shooting, it may go ahead.

This story tells the most – it tells those who aren’t rich enough or who don’t kill for fun that we must accept the strictures, that no exemptions will be made for our errant behaviour, for our dyings or our burials, for our longings or our needs.

The very words ‘game’ and ‘shooting’ seem invidious. The millions of creatures slaughtered annually by very rich people wielding absurdly costly guns, seem nothing like a game. But values, in this particular disordered world are different from those by which most of us live.

In this other world, the natural inhabitants of the land, including some of the most endangered, are seen as either sources of revenue or ‘vermin’ to be exterminated, sometimes illegally snared, trapped and poisoned.

The land on which ‘game’ shooting takes place isn’t seen as part of an entire eco-system (the one which makes up the country, the continent, the world) but as a personal fiefdom where the natural world has no role, where money and killing are the sole determinants of its management.

The irresponsible annual burning of the moorland peat causes vast ecological damage in the release of stored carbon and degradation of existing peat bogs as many species and their habitats are relentlessly destroyed.

Flooding, already increasing as a result of climate change, has become a major hazard for those living below the moors. There are few sights more dispiriting than a burning grouse moor, the fast run of flame, the low lines of smoke, the knowledge of the creatures condemned to burn in order to allow the rich to play.

The long-held Western idea of ‘human exceptionalism’ which suggests that humans are superior to all other species and as such, entitled to behave towards them as we choose, seems, in the case of game shooting, super-charged when the rich can dominate the earth itself, illegally slaughter our wildlife and cause massive destruction while bearing none of the cost or the responsibility.

For those whose preference is the less expensive practice of shooting partridge and pheasant, an estimated 27 million birds are imported annually from Europe as poults or eggs. Reared in factory farm conditions, the birds are then released for the purpose of being shot.

Many escape, with unknown effects on local wildlife with whom they will compete for food. So many birds are killed on shoots that they’re nor considered worth collecting as food – they’re thrown into the ‘stink pits’ used to attract and snare other creatures or abandoned as waste.

This disregard makes so much of the culture surrounding ‘game’ shooting unaccountable. Despite assurances in shooting literature and websites about ‘respect’ for the shot creatures, there seems little respectful about photos of men (for it is mainly men) grinning behind rows of dead birds or mountain hares. More unaccountable still is that among the items offered by the companies selling the most expensive guns and accoutrements to the shooting fraternity, many bear the images of the dead, discarded creatures. Rendered in glass and silver, on watch faces, napkin rings, decanters and prints of unsurpassed tastelessness, grouse and pheasants appear in the vigour of their lives.

It is an aesthetic of delusional atavism, surviving in the shadow of the mass slaughter of wildlife which took place during the Victorian era from which many species have not yet recovered. There’s the uneasy blend too of unacceptable attitudes implicit in the culture, one typified by Boris Johnson’s repellent praise for hunting when he wrote of the ‘semi-sexual relationship with the horse’ in hunting with dogs and the ‘military style pleasure of moving as a unit’.

Perhaps these stories together should tell us something, alert us all to the harms being done to the land and to society by the very, very few. What they should tell us too is that the moment has to arrive when the right of the wealthy and powerful to destroy our countryside and our wildlife should end, and it has to arrive soon.

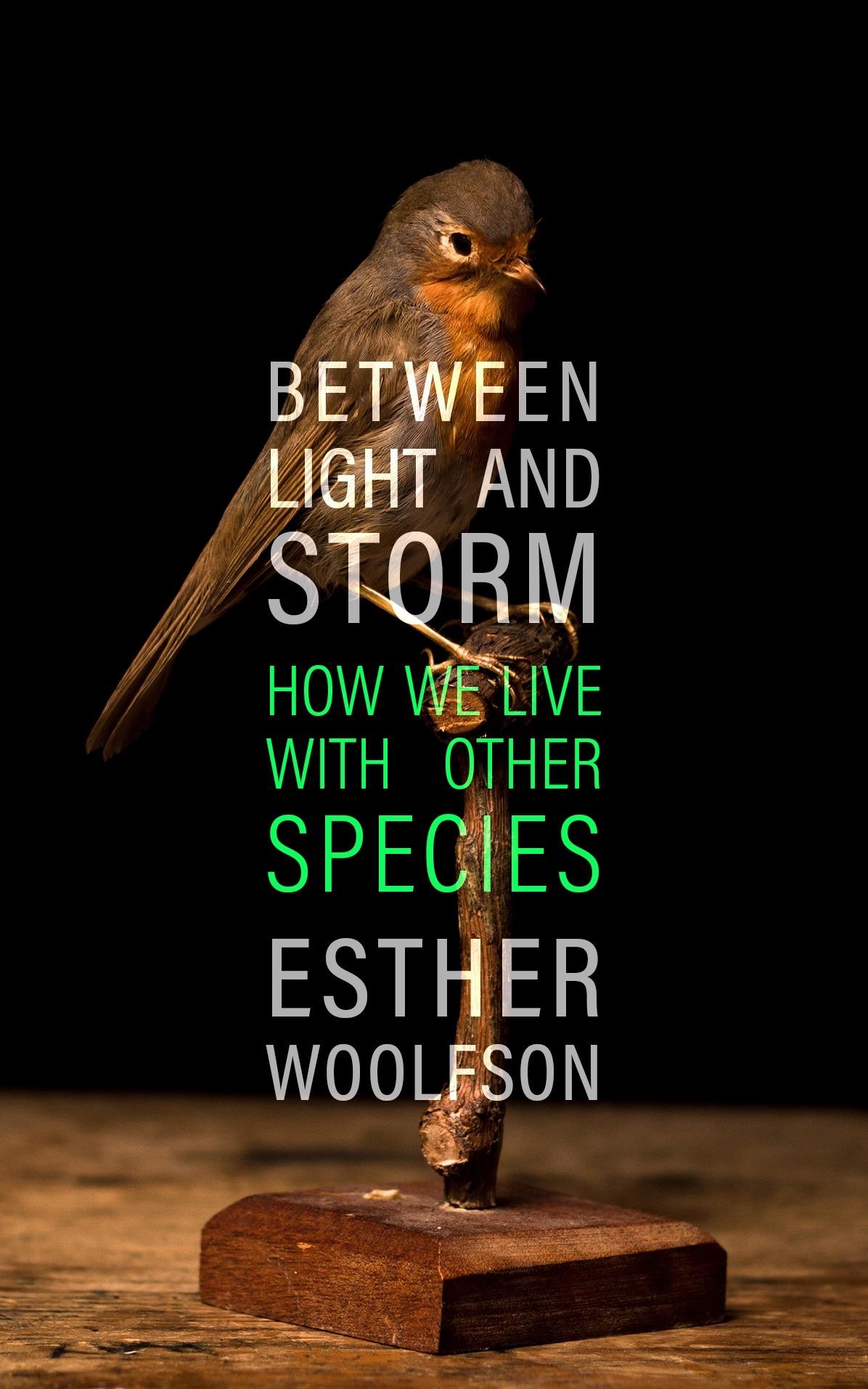

Between Light and Storm: How We Live with Other Species by Esther Woolfson, published by Granta

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel