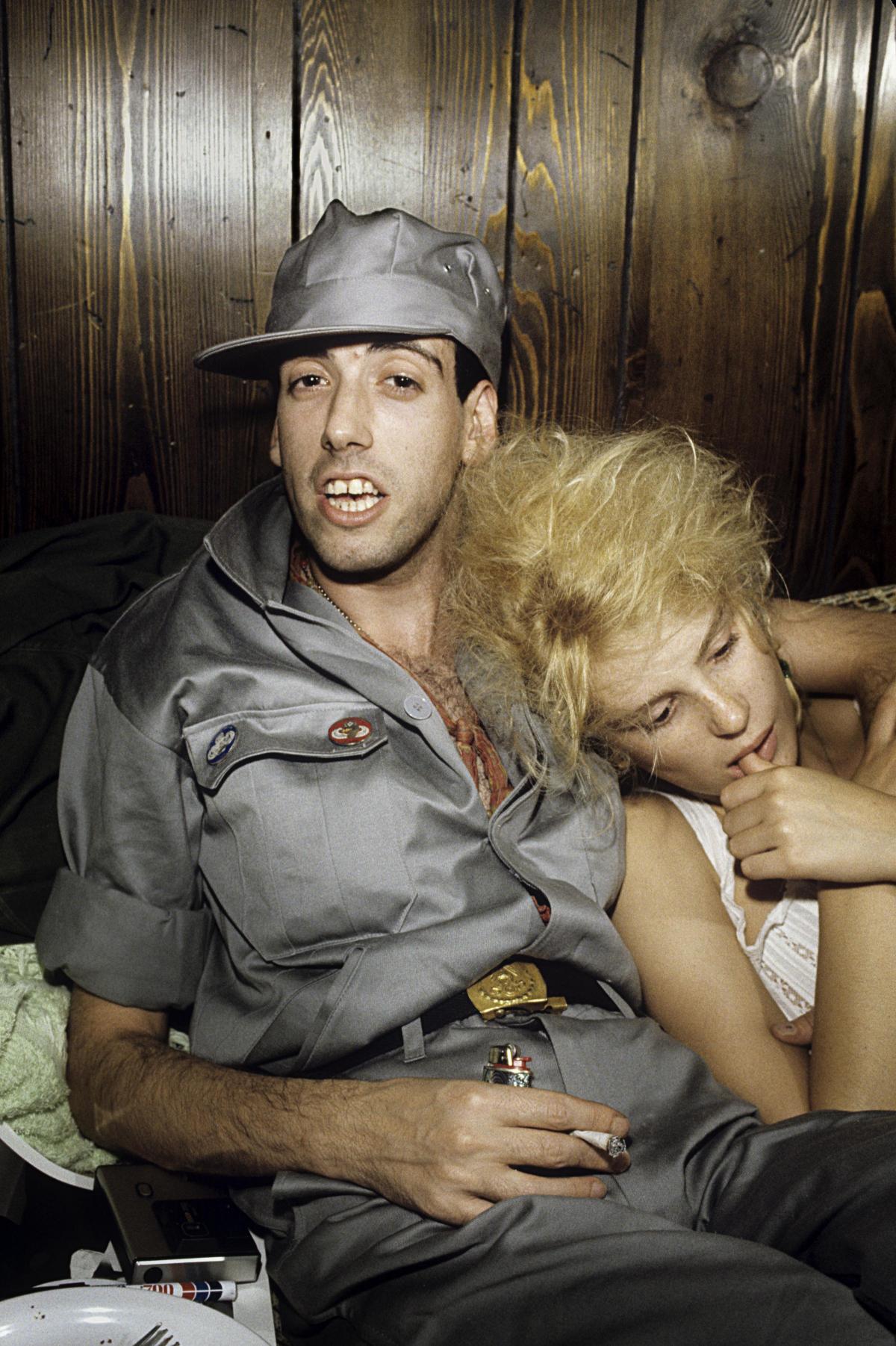

TOWARDS the end of his new book Punk, Post Punk, New Wave, a compilation of images he took back at the end of the 1970s and the start of the 1980s, the photographer Michael Grecco sums up what that particular time meant to him.

“Upon reflection, looking back forty years,” he begins, “you have to think: ‘Wow, what an amazing life. Now, given my upbringing with an oppressive old-world Italian mother, of course, at times I felt guilty about it. You slept with someone new every night, you were always doing drugs, you were always drinking too much. I was having not just fun, but debauched fun – sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll.”

Sex and drugs and rock ’n’ roll. More than four decades after the events chronicled in Grecco’s book we can argue about what punk rock meant back then, what it might still mean in the 21st century. We can look back at its nihilism, its otherness, its politics, its year-zero approach to pop culture and how that rippled out into the wider world.

But at some level it was always just another story about young people having fun in the messiest way possible. Grecco was one of them.

And so in the pages of Punk, Post Punk, New Wave there’s less talk of politics and principles and manifestos, more pictures of Wendy O Williams, from punk band the Plasmatics, topless, and a more or less naked Lux Interior of the Cramps (both onstage and off). And page after page of boys and girls posing with guitars.

Grecco’s photographs offer grungy visions of stage-front anarchy and back-stage intimacies. They are often as rough and ready as the music and musicians that inspired them. You could push it and say Grecco’s book is the visual equivalent of a Ramones single, a noisy explosion of images that catches the energy, the aggression and the chaos of the moment. “One, two, three, four …”

Grecco, who has gone on to become one of America’s foremost commercial photographers, shooting for everyone from Time Magazine and Newsweek to Sports Illustrated and GQ, was both a reporter of and participant in the punk scene that emerged in the United States in the late 1970s.

Having grown up in a restrictive Italian-American family in New York before moving to Boston in 1976, punk was something of a revelation to him. He’d grown up and “music snob” and a jazz fan. That was all to change. “Walking into my first punk club in Boston at age 18,” he writes, “I found I suddenly joined a club where everybody belonged. I could finally be myself, or at least find out who I really was.”

From 1978, Grecco spent many nights in sticky-floored Boston clubs (and sometimes elsewhere) watching bands and taking their photographs (for local magazine Boston Rock) and sometimes having to dodge metal milk crates thrown by up-and-coming superstars. (A disgruntled Billy Idol in that particular case: “The corner of it sticks in the drywall next to me. I just moved out of the way in time.”)

Boston was a useful calling point for British artists, hence the appearance of Public Image Ltd, Elvis Costello, Lene Lovich and Joe Jackson. In the book, Dave Wakeling of The Beat suggests that Boston felt like a cross between London and Dublin and so was comfortingly familiar.

These days, you could argue that punk has become something of a palimpsest. It’s an idea that has been written over and then over and then over again so many times that it’s difficult now to see your way back to it. Grecco’s images offer a window into the past that frames it as a raucous, rowdy, rough-around-the-edges take on rock, a kind of back-to-basics that delivered music from the excesses of the early 1970s, and the now decadent giants of the 1960s (“No Elvis, Beatles, or The Rolling Stones in 1977,” as the Clash sang.) A musical reboot, if you like.

That rather leaves out the more interesting ideas that punk played with, whether that be Malcolm McLaren’s situationist-inspired pranksterism or the Clash’s sometimes infantile, sometimes inspired political outspokenness. They were great supporters of Rock Against Racism, after all. Which, as an aside, does make you wonder how Boris Johnson could name them as his favourite band last year. Another example of Tory gaslighting? Or further evidence that the Prime Minister has never been much of a details man?

What should also be noted about the Clash was that they were musically adventurous, a band who embraced reggae and rap as well as rock. It’s what marked the best of the punk artists, from John Lydon to Siouxsie Sioux. And it’s why what came afterwards, post-punk, was so outward looking, embracing electronica, disco, soul and jazz.

Those changes can be seen in Grecco’s book. There are photographs of Adam Ant, Madness, The Specials, the B-52s and New Order to be found here. There’s even a picture of the late, lamented Stuart Adamson from his Big Country days.

But, really, this is a ground-level vision of punk and its musical descendants, one that plays up the sometimes dangerous, sometimes disreputable, fun of it.

Also near the end, Grecco writes: “If you were drinking heavily – and we were always drinking heavily – we would end up eating Chinese food at 4 am … You would then crash, stumble to work, take a “disco” nap at 6pm, after work, and go out again at 10 or 11pm, every night. Oh, to be young again!!”

That’s the nub of it, really. If any of us could travel in time wouldn’t we always go backwards?

Punk, Post Punk, New Wave: Onstage, Backstage, In Your Face, 1978-1991 by Michael Grecco, is published on November 10 by Abrams, priced £30 Photographs © 2020 Michael Grecco, Iconic Images

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here