STANLEY Baxter has come out as gay, revealing for the first time that his marriage was a façade. His biographer Brian Beacom examines why the brilliant Scots entertainer with a thousand faces refused to show his real one to the world.

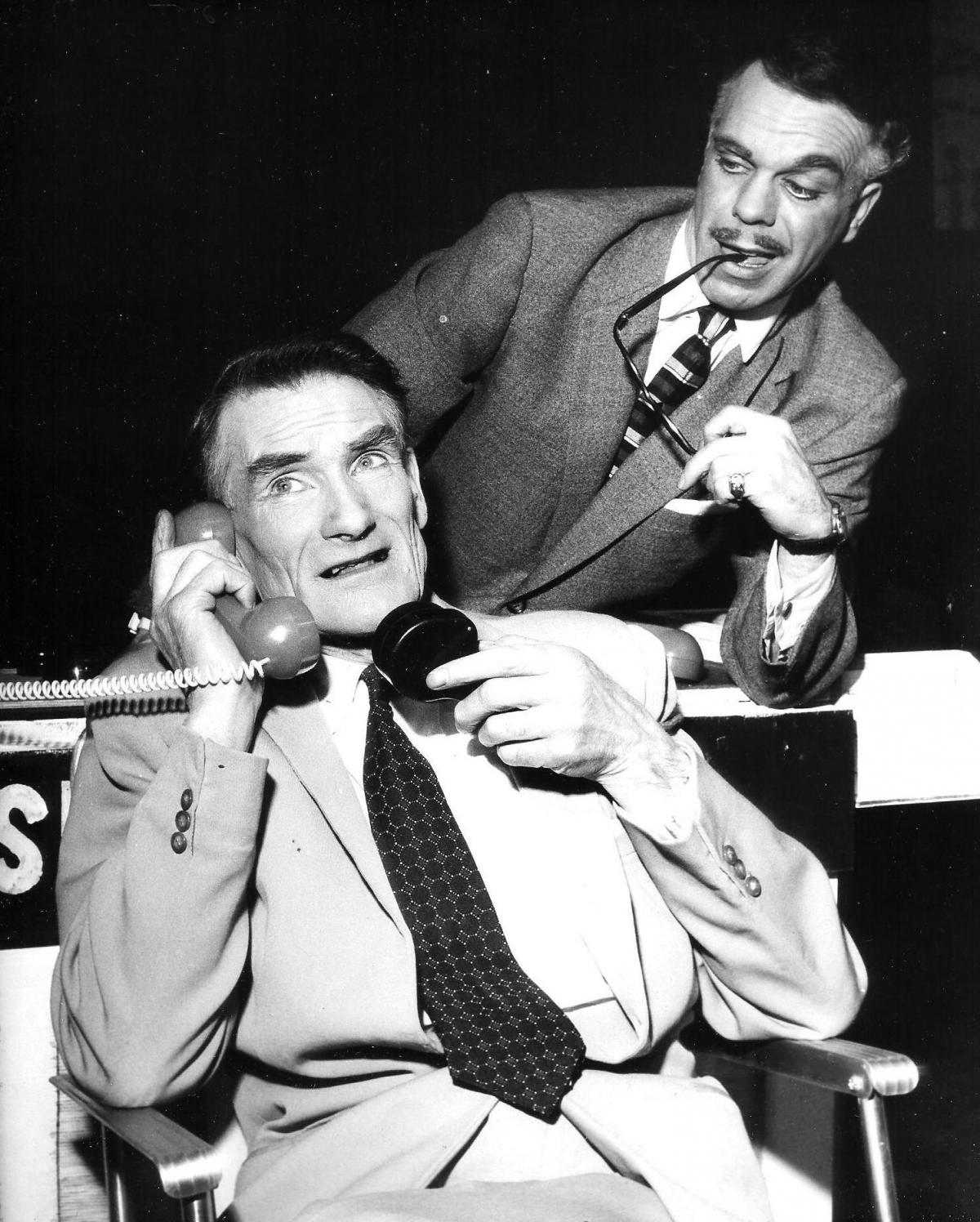

IN MARCH 1952, 26-year-old Stanley Baxter, recognised as the brightest young star in the Citizens’ Theatre Company, made a decision that was to shock his parents, stun his close friend Kenneth Williams and even surprise himself.

In the front room of Moira Robertson’s parents’ home in Dumbarton, Stanley slowly, cautiously, uttered the words “I do.” He failed to convince. His performance of Eager Young Husband was the worst he would give in his life. Stanley would indeed come to regret it for the rest of his life.

And the decision may have played a part his wife’s untimely death.

Why did Stanley agree to marry Moira? The dark, often highly dramatic script of their life together began when he joined the Citz in 1948, shortly after being demobbed.

Stanley walked through the doors of the Gorbals theatre and into theatre heaven, loving this avant-garde world populated by the likes of Sybil Thorndyke and Duncan Macrae. “It was all I ever dreamed of.”

This wasn’t unrestrained hyperbole. He had indeed dreamed of being a professional actor since appearing on stage as a seven-year-old at local talent contests. By the age of 14 when he became radio star he knew where his destiny lay.

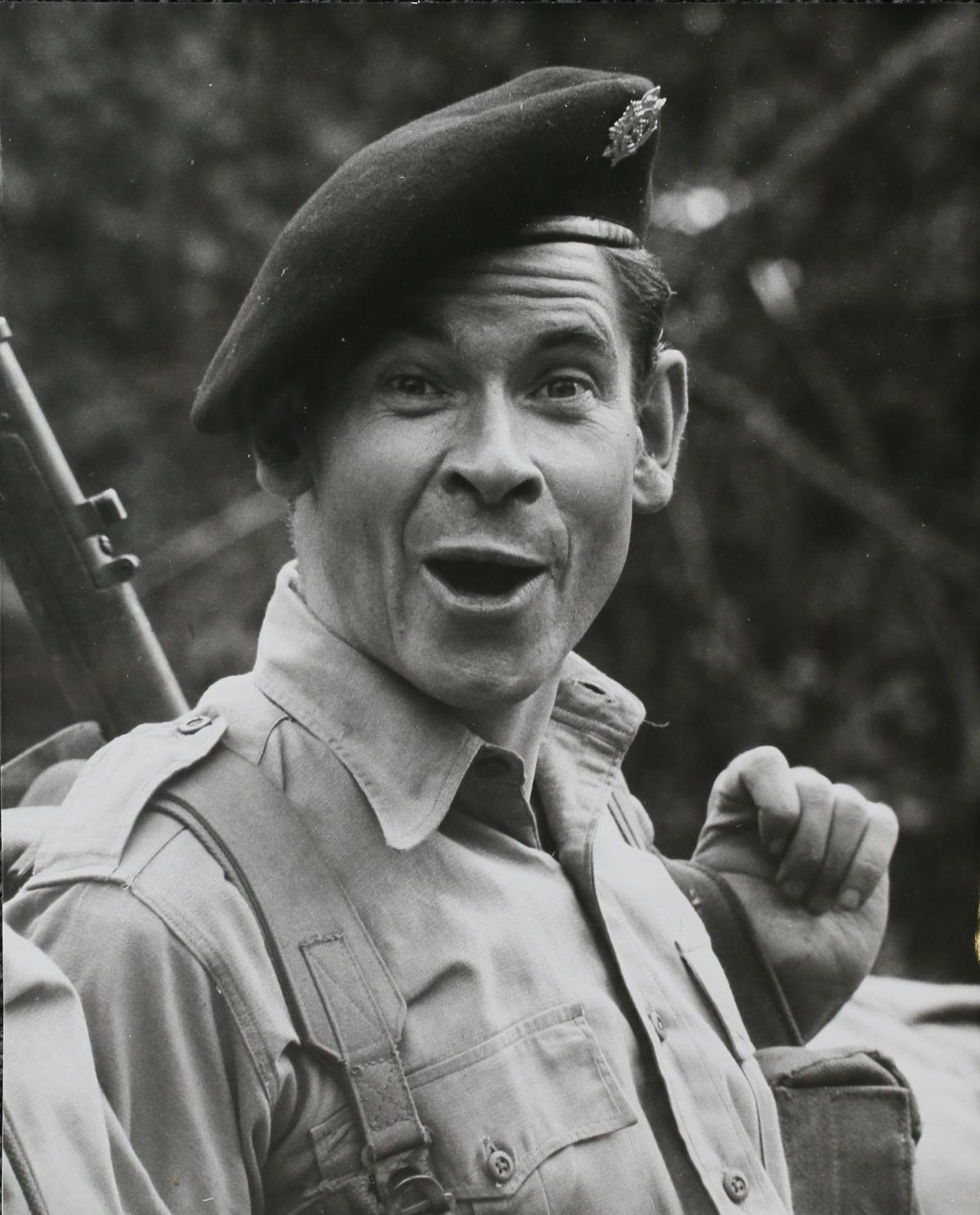

And by the time the then-teenager landed a place in the entertainment corps during his National Service years, Stanley was convinced that acting was his destiny. But in joining the Citz and aiming for the stars (however small his initial parts were as an Assistant Stage Manager) the young actor realised his sexuality could prove to be his downfall.

“The Citz was a heterosexual theatre company. It wasn’t like theatres of today, which are heavily populated with gay people. I felt vulnerable. I felt I had to be very careful not to allow anyone a glimpse of my predilection.”

And then he met Moira, this soft-spoken chic young woman with the Bette Davis eyes. This builder’s daughter and art school graduate was a clever and attractive, if rather ethereal, young woman. As spring approached, Stanley saw even more of the woman with the hooded eyes, even taking her along to his parents’ home at 5 Wilton Mansions in Glasgow's Kelvinside.

The pair developed a closeness that meant when they weren't working they enjoyed a movie or dinner together. However, it was Moira who was determined to take the relationship to the next stage. “Moira chased Stanley,” says Stanley’s sister, Alice. “There's no doubt about that. She kept calling for him and my mother wasn’t too happy about this. In fact, Mum showed her disapproval of Moira right from the start.”

Stanley agrees. “My mother didn’t think any woman was good enough for me [Bessie Baxter’s principal purpose in life was to grow a showbiz star] but there was more to her criticism of Moira. Early on she used to say, ‘That woman's following you around like a wee dug!’ And she was right. There was a sort of obsession.”

Stanley and Moira worked on a range of productions at the Citz together but the spring of 1949 saw the company move down to Ayr for the summer season and Stanley and Moira had lots of fun together. It’s hard to know if the invigorating sea air – or simply timing – resulted in Moira’s declaration, but she announced she wished to have a full-blown sexual relationship with her leading man.

Stanley was up for the challenge. But it was a whole new experience. Yes, as a 14-year-old he’d had a frolic with the maid (despite living in a West End tenement Bessie Baxter insisted upon live-in help) but this was an entirely new adventure. “I guess I had come to really like Moira. The more I got to know of her I realised she was a lovely person, a woman of enormous heart.”

Yet, the relationship was doomed from the start. Stanley knew he was gay. Experiences in the Far East during his concert party stint confirmed to the Scot where his heart lay.

Early on, Stanley had hinted at his preference to Moira. But she ignored the signs. Stanley weighed up what this all meant. Should he push aside the attention of this attractive, classy young woman?

“I was apprehensive about getting involved for all the obvious reasons. Yet, I had all sorts of excuses for developing a relationship. It was partly a feeling of ‘I'll show them’, that I could be as heterosexual as the rest of them.”

He was also aware of the need to have a cover. In 1949, it was illegal to be gay and entrapment of homosexual men by covert police officers was common. Alec Guinness and John Gielgud had both been charged with Importuning. Gay men up and down the UK lived in constant fear of having their careers and lives wrecked.

“The relationship made a sort of sense,” says Stanley. “And the sex was ‘fine’ – not rockets going off or anything.”

Moira meanwhile, had pushed aside question marks against Stanley’s sexuality, partly because she adored her boyfriend and loved his talent.

In December at the Citz, Stanley and Moira starred in the Christmas panto Red Riding Hood (Stanley played Granny McNiven, Moira played Red Riding Hood). The critics loved it. But unknown to the world, Granny and the eponymous hero had decided to marry. Kenneth Williams was among the first to be told – and he couldn’t believe his ears.

What Williams didn’t know, however, was the pressure Stanley had been under. “I had felt the relationship simply had to stop, so I broke it off. However, Moira was very, very upset. I kept getting those sheep’s eyes every time she passed me in the theatre and she appeared to be heartbroken. Then one night she invited me for my favourite spaghetti up to her little rented flat at 65 Clouston Street and I was seduced back into bed again.”

The appetite sated, Stanley reckoned the only way to break off the relationship once and for all was to be entirely honest with Moira. “I told her my preference and said, ‘That’s why I am breaking off the relationship. This would be NO life for you, married to someone who is essentially and primarily homosexual!”’

Moira's reaction was surprising, even to those who knew how liberal she was. “She looked up at me, shrugged and said ‘Oh, I don't care about that at all. You mustn't let that worry you’. And I said ‘Well, it does worry me. I don't think you know what you're talking about and I don't think you realise that the future will be bleak for you and difficult for me.’”

Stanley was adamant. He told Moira the relationship was over. For good. Suddenly, she raced to the front window of their second storey flat, opened it and climbed out onto the window ledge, yelling, ‘If I can't have you then I won't settle for anyone else!'

Stanley was terrified. His heart raced as he rushed towards her and pulled her back. “I tried to keep things calm and said, ‘Okay, okay, well if you want to get engaged, we could try it for a year or so and see what happens’.”

Just after the window ledge moment, Stanley was handed a Get Out of Jail Free card. Moira wrote him a very sane and balanced letter. It said, words to the effect of, 'I'll let you off if you don't want to marry me'. This was the defining moment of Stanley’s life. He had his chance to make a clean break, to move on alone. And he turned it down. “By that time, I had so many tender feelings for her,’ he explains. “I thought she would be still be heartbroken. But of course I should have been stronger. It was real weakness on my part.”

It was more than weakness. It was absolutely selfish. Kenneth Williams certainly thought so. “Kenny thought I was making a terrible mistake,” says Stanley.

Williams believed Stanley to be taking advantage of Moira and a traitor to the cause. And why shouldn't he? After all, the pair had spent endless hours discussing sexuality, preferences and honesty. Kenneth asked Stanley what future he could expect if he married Moira Robertson. Stanley asked the same question of himself – but pushed the answer aside.

Did Bessie Baxter have any idea of Stanley’s true sexuality? If she did, she never let on. And she never knew of the window ledge incident. But she did mention several times there was ‘something wrong’ with Moira, that her emotional balance wasn't quite right.

Meanwhile, on January 15, 1951, the engagement became national news, yet this didn’t really register with Stanley. He reckoned it would at least a few years before the couple arrived at Wedding Central. But just weeks later he realised he had boarded a runaway train.

A year later, on March 5, 1952, the train sped west to Moira’s parents’ home in Dumbarton for the ceremony. Fred Baxter, knowing his son was unconvincing in the role of Happy Groom, attempted a last-minute derailment. “My dad said ‘This is a very big step you're taking, Stanley. We hope you've really thought about how important it is.’

“And I said nonchalantly, ‘Oh, not nowadays. If it doesn't work out, you just get divorced and you move on.’ And my father replied with a very heavy voice, ‘No, it's not as easy as that.’

“And he was so right.”

The following Monday, the Scottish Daily Express wrote of the 'quiet' wedding. "Stanley Baxter and his wife Moira were secretly married in the drawing room of the bride's house in Dumbarton. She then went to their new Glasgow flat to cook spaghetti for his supper."

Their new home, a large ground-floor flat, at 73 Clouston Street, was just a few doors along from Moira’s previous flat. But what the Daily Express didn’t know was that when Stanley arrived home, with the sound of Saturday evening theatre applause still ringing in his ears, he broke down in tears. The honeymoon night – predictably – was a disaster. “I sat on the edge of the bed and sobbed my heart out,’” he admits.

“Moira asked me what was wrong and I said something about the emotion of it all. But it was because I knew I'd made the biggest mistake of my life.”

What could he do? He had to get on with it, focus on finishing the last 10 days of the panto season – and his last 10 days at the Citz. He had to get on with his life.

In 1959, Stanley realised the writing was on the wall for variety theatre in Scotland and moved to London. But had Moira truly leapt at the idea of leaving Glasgow and friends and family behind? “Moira didn't ever leap anywhere,’ he says softly. “She wandered, like Ophelia through Hamlet, but she would have moved to the ends of the earth for me.”

In London, Stanley found immediate success with TV satire On The Bright Side. Just a couple of years later he landed a five-picture deal with Rank Films. Moira’s role, however, was reduced from Actress to Wife.

Stanley reckoned his wife's place was in the home. “I didn't think that she was ever going to make it very big and I suggested she give it up. I shouldn't have done, but I did. It was all very selfish of me and a bit macho. She now had to be a housewife, which she found very frustrating. And although she was a good cook, she wasn't very good at washing. The pulleys were always full of stuff.”

Moira was more Dora from David Copperfield than Glaswegian domestic goddess. She may have worshipped Stanley but she never got herself worked up if her husband’s white shirts were dry in the morning or not. “I know it all sounds terribly old-fashioned but men had those expectations in those days.”

Now, Stanley admits another reason why he felt Moira should remain at home. “I believed that no-one in our family should be anything but a star.”

Two years into the marriage, relations with Moira were "fine", but the sex was dwindling. Moira wasn’t entirely unhappy with the situation. After all, she was with the man she adored. And wasn’t marriage about compromise?

Meanwhile, Moira had landed part-time work with a milliner – but it didn’t seem to hold her interest. And Stanley noticed her little eccentricities, her remoteness, her rejection of life's boring rituals of cleaning, cooking, washing laundry, had become more pronounced. But he didn’t tackle the issue.

In January, 1962, he was focused hard on his career. Bringing the very best to his latest film role, Crooks Anonymous, starring alongside Julie Christie and Leslie Philips. But Stanley couldn’t contain his sexual frustrations. One night on his way home he was arrested after being entrapped by North London police in a toilet and charged with Importuning.

Stanley managed to survive the threat to his career – just – and Moira, as expected stood by her man.

But over the years, Moira’s mental health issues worsened. She became disruptive. She would turn up at the stage door in Glasgow, unannounced. She once flew to Belfast to be "reunited with the spirit of [theatre director] Tyronne Guthrie." Stanley had to move out, he says, for the sake of his own sanity.

Moira tried to take her own life on two occasions. But Stanley, and Moira’s family, coaxed her to take medication. And it worked. And as the years progressed, the medicated Moira and Stanley became close again. They would meet for lunch every day.

Tragically, however, in 1997, the year Princess Diana died, Moira took her own life. Unknown to Stanley, Moira had ditched her medication and the demons raged again. He says: “Did she carry some hope that I would get off the plane, rush round and save her again? Should I have taken her to Cyprus? Would it have happened anyway?

“We'll never know.”

Moira’s death left Stanley bereft. And since that time he hasn’t been able to surrender the thought had he not married the fragile, vulnerable woman she may have lived more of a happy life. “I’ve often wondered how her life would have turned out had she married a devoted heterosexual husband.”

He adds, his voice breaking: “I will never know why she loved me so much. And I did love her deeply, in my own way.”

The Real Stanley Baxter, by Brian Beacom. Published by Luath Press Ltd, £20.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel