IT started out as a bike ride. Three old friends, in every sense, cycling across Spain – a country that has obsessed and united us all our lives. It became a coast-to-coast tour of a distinctly iffy busking band. For two of the cyclists it was a celebration of retirement. For one in particular, a voyage of remembrance and loss. We hadn’t expected we’d be pedalling through the past as much as the present.

And I for one had no idea how a wee adventure with pals would mess with my head. As Alan Brown, fellow writer and cyclist, put it: ‘You can be gallus enough to busk across Spain but your demons and weaknesses still come with you.’

Liam Kane, Eddie Morrison and I met at Glasgow University – 45 years ago. That fact alone induces gratitude and trauma in equal measure. Dealing with life’s gifts, and its toll.

We know sport is good for our minds as well as our bodies. Had it not been for regular cycle rides with Eddie and Liam – we’ve been pedalling around Spain and Scotland for years now – I would have had many more slumps and dark days.

Exercise pumps out feel-good endorphins. It gets us out the house (all the more important in these Covid days). Cycling and walking with friends creates and seals connections and a sense of community. But nobody warned me that, sometimes, the cure can trigger the symptoms.

Early on in our coast-to-coast ride, on a warm day when everything should have been right with the world, I took a tumble. Not off my bike, off my nut. We had just left a joyous village festival where we busked in public for the first time. The hills of Galicia were beautiful. Yet, as we cycled, my interior landscape began changing faster than the topography. Memory and dreams whipped themselves into daymares. A much-loved country looked alien, the spring sun hot and dangerous, close friends distant. The weight of all that’s remembered.

Dodo had got me…

How useless a creature that allows itself to be hunted to extinction even though its meat was famously greasy and bitter. It’s mocked by its very name – probably from the Dutch dodaar, meaning ‘fat-arsed’. We only recall it now in the phrase ‘dead as a dodo.’ It also happened to be a nickname of mine from schooldays, not ill-intentioned, just onomatopoeic.

A 1627 description of the flightless bird: ‘The body is round and fat... The visage darts forth melancholy. Small and impotent… the eyes small, round and rowling.’ Statistically, around a quarter of people reading this already recognise Dodo, albeit in a different form and with your own name for it. (The old joke: if you have three sensible mates, you’re the bamstick.)

Depression, be it persistent, bipolar, seasonally affective or manic, situational or mood disorder touches us all, directly or indirectly. Fat and clumsy, Dodo is always there or thereabouts, hiding in the rushes of your subconscious, suddenly, uninvited, flumping out directly in front of your eyes so you can’t see beyond it. And it sits there spitting and snarling and telling you how things really are.

Look at you. Cycling across Spain? You’re a slouch, a self-serving birkie in your own rash wee tinsel-show… Whatever the situation, Dodo finds a way of revealing the underside. It eats your unspoken words so that next time you’re in company all you have left are grunts and silences, wary eyes.

For those who don’t have a dodo, or black dog, or shadows of their own, you seem deliberately sullen. You get anxious about everything: your tyres, some small thing that happened ten years ago, why all drivers hate cyclists, the state of the world… You’d have to be crazy not to be mental. Dodo can stay with you for an hour, or a month. For some unfortunate people, it never backs off, God love them.

I hadn’t trained enough and was lugging my unfit carcass, a heavy old laptop, recording gear and bike maintenance tools I can’t use, with a fiddle strapped to my back. In further self-defence, I was retracing a journey I had attempted to make when I was a teenager. In the 1970s I had set out to follow Laurie Lee’s footsteps in As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, busking solo with my violin through Spain. I failed – my brother had to save me. Lee was rescued for the more dramatic reason of escaping the violence of the Spanish Civil War. Part of my new book, Everything Passes Everything Remains, is solving the puzzle of why I gave up back then.

How we construct our life stories impacts on how we view the world and feel about our position in it. As we moved eastward into León, through Valladolid, we became interested in how not only individuals seek meaning in their experiences and pasts, but communities do too.

Eddie, Liam and I compared memories of our first journeys in Spain. The past colours the present. On this trip Eddie was grieving the recent passing of his wife, and our friend, Lizzie. Liam was cycling towards family now living in Valencia. Laughter, loss, anticipation fluctuated as unpredictably as the weather, clouds passing, sunbursts.

Tordesillas is a place that demonstrates the arbitrary nature of historical memory – a major issue in Spain right now, still healing from the Civil War, and Franco’s cruel regime. What nations choose to remember, and forget.

A little town in Castile, Tordesillas is of global significance. Two years after Columbus ‘discovered’ the Americas in 1492 the Spanish and Portuguese were already arguing about who was going to ‘own’ these newly-found lands.

The courts of the Catholic Kings and of King Joao I of Portugal decided that jaw-jaw was better than war-war. Mainly because neither side was confident of winning. At the negotiations they drew a line down from the north pole of the known world to the south and agreed that everything west of that line would belong to Spain and everything east, Portugal. The Spaniards thought they had outmanoeuvred their rival, but eight years later a Portuguese fleet anchored at a shoreline that turned out to be the massive landmass that sticks out, eastward – Brazil. Which is why the vast majority of Central and South America speaks Spanish, but in Brazil they speak Portuguese.

The people of Tordesillas are proud of their treaty. It prevented a war. But what they were agreeing was the total colonisation of a vast part of the world that led eventually to millions being enslaved, and in some regions, outright genocide. To lands being stolen and exploited – churches all over the Peninsula are still ‘decorated’ by gold and silver and gems torn from conquered lands.

And it’s still being cited, the Treaty of 1494. In the 1980s, the UK and Argentina argued over its interpretation to determine who ‘owned’ the Falkland Islands. And there is another direct consequence, one that links Spain’s past with Scotland’s. Over the last decade, since my novel Redlegs, I’ve been involved with our own problems of historical memory. We’re in denial. Liverpool, Bristol and other English cities have museums, plaques, bearing witness to how their prosperity owes much to the most audacious and barbaric slave industry in history. Scotland has been slow to come to terms with its own past. Only now, through the work of Dr Stephen Mullen, Sir Geoff Palmer, Professor Tom Divine and others across the old British colonial world, are we coming to terms with the source of our wealth.

A 525-year-old pact. Yet that Spanish past is even now being vaunted as an ideal. Recently Pablo Casado, leader of the Partido Popular, said it was, ‘the most important landmark of humanity… probably the most brilliant era, not only of Spain, but of Man.’

Yet, throughout our Spanish journey, we were often told Don’t Mention The War. Events of 70 years ago, or the end of Franco’s rule only 45 years ago – when I was on my first busking trip – are too long ago to bother about. Leave the past in the past. Unless it’s a glorious victory or treaty that supports your idea of national identity. Entire peoples can have borderline personality disorder.

And split personalities. Although Catalonia wasn’t on the route this trip, it was everywhere. At the very mention of the place polite conversations erupted into furious rows, violently opposed interpretations of the 1978 Spanish Constitution, personal and political acrimony. It seemed to me that men, particularly older men, became the most agitated.

And throughout our cycle, in Spring 2019, we were getting news of the equally rancorous brawling over Brexit. It’s not only your own demons you carry everywhere with you but your nation’s – or nations’. We worried about the big bad world, beyond the pretty cycle routes. A feeling we’re increasingly at the mercy of an emotionally illiterate political class.

This sounds like we had a terrible time of it. We so didn’t! Our journey was deeply healing, and fun. Since returning I’ve found out more about such organisations as Brothers In Arms. Male suicide is alarmingly on the rise. It’s crucial that we find a way of allowing men to open up, connect with each other. There is something therapeutic about cycling – or whatever your sport is – with friends. The focus, the banter, escape, the mutual cooperation.

Everything Passes Everything Remains chronicles the people we met along the way. Generous souls (90 year old Visitación, for example, sharing her dramatic memories of the Civil War), other buskers, travellers, people who have never left their villages. We played fiddle, uke and whistle, sang Scots, Basque and Mexican songs, compositions of our own. Sometimes to no-one in particular, on haystacks and in fields, anywhere we reckoned a song might sound good, just for the joy of it. On one occasion, we videoed our take of that great classic ‘Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep’… (to show that we’d been cycling, traffic free for miles – in the Middle of the Road.) That’s another kind of madness – optimistic and daft. Essential to any kind of sanity.

Getting older brings new trials. Carl Jung proposed four stages of life. Well, in our 60s now Athletic we ain’t – just getting on our laden bikes was a daily challenge. Certainly not Warlike – all we wanted to conquer was the odd Category 1 hill. Any Statement we’ve made in life, too late to change it much now. Although the book has a series of pen portraits – Don Quixote and Gabriela Cunninghame Graham among them: people who reinvented themselves, in ways I argue helped them become themselves. Perhaps it’s never too late to find more inside us. But this trip was really about approaching Jung’s final stage – the Spirit. The three of us – the Atheist, the Believer, and the Agnostic – continued a decades old conversation on meaning and purpose between pedalling, eating tomatoes in village squares, singing and meeting people. Seeing the end in sight (and I don’t just mean Valencia) has its upside: work, possessions, influence matter less. Thinking, and thinking back, the hymn of tyres on tarmac, cool fountain water after a sweaty climb… the immediacy, and often the beauty, of the moment absorbed us.

While it’s true that, in retracing difficult times in our life stories – and in Spain’s and Scotland’s –there are divisions and absence, dreams unfulfilled, a wary eye on Dodo, they were outshone by music, laughter, poetry and friendships old and new. Accompanied by Lorca and Rosalía de Castro, Laurie Lee, Heaney, Ethel Macdonald, St. Theresa of Ávila…

There’s something zen about the repetitive push-down pull-up of pedalling, sighing along hidden roads in less well-known parts of Spain. Contemplating the past-in-the-present, and the present-in-the-past. Coming to terms with yourself and the world you inhabit. Keep moving forward. Everything passes, but everything, in important ways, does remain. And keeps us sane. Or sane enough.

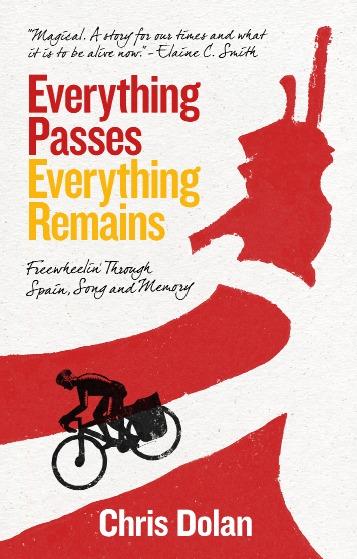

Everything Passes Everything Remains: Freewheelin’ through Spain, Song and Memory, Chris Dolan, Saraband, £9.99

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel