Billy Hutchinson has journeyed from UVF killer to helping forge the Good Friday Agreement. He’s just brought out his autobiography. Here, in conversation with Writer at Large Neil Mackay, he discusses the risk Brexit poses to peace in Ulster, the debate around Scottish independence, and the role Scotland played in the Troubles

SCOTLAND often forgets its long, and sometimes tortuous history, with the north of Ireland. The intimate relationship between the two countries goes back millennia, through ties of family, tradition, language – and even the spilling of blood.

From the ancient Gaelic empire of Dalriada, which encompassed the north of Ireland and the west of Scotland in the Dark Ages, through the plantation of Ulster by Scottish settlers on behalf of the Crown in the 1600s, all the way to the brutal civil war euphemistically named The Troubles, the two countries share bonds, often painful, like few other nations on Earth.

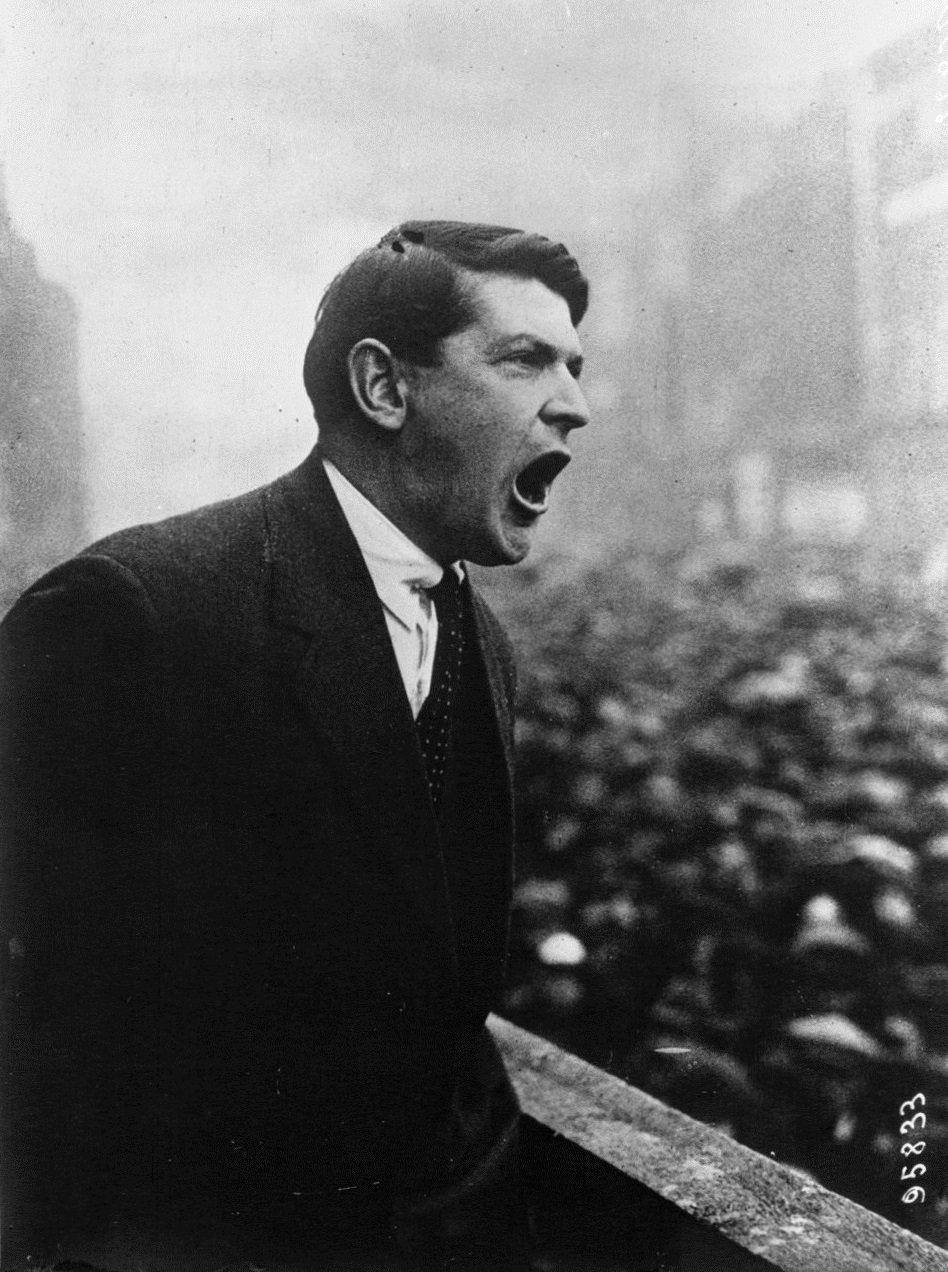

Billy Hutchinson is a physical reminder of how Scotland – and its culture and history – fed into both sides in the recent conflict, inspiring and supporting both republican and loyalist paramilitaries from the 1960s through to the ceasefires and peace process of the 1990s. He took his first steps on the road to violence when he became part of Northern Ireland’s notorious Tartan Gangs in the late 1960s – groups of loyalist youths, some of whom would eventually go on to become hardened terrorists.

The Tartan Gangs were inspired by the ties between loyalists in Northern Ireland and the west of Scotland – ties also mirrored in separate bonds between republicans in the north of Ireland and across Scotland.

Hutchinson would go on to become a leading member of the loyalist paramilitary group the Ulster Volunteer Force during The Troubles. He served life for the cold-blooded murder of two Catholics, but after 15 years in the Maze Prison – where he earned a university degree –he abandoned the gun and turned to politics.

He would go on to play a pivotal role in the peace process, helping to convince loyalists to declare a ceasefire, which eventually paved the way for the Good Friday Agreement. His election to the Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont in 1998 as an MLA, the equivalent in Northern Ireland of an MP or MSP, marked a significant milestone on his journey from man of violence to man of peace. Today, Hutchinson is a Belfast city councillor.

He just published his autobiography My Life In Loyalism, co-written with Gareth Mulvenna, a Catholic academic. It is a timely reminder – as violence again bubbles under in Northern Ireland in response to Brexit, picking at old wounds and reigniting tensions around the border – that political violence in any form is the road to ruin.

Tartan Gangs

The Shankill Road is the heart of loyalist, Protestant Ulster. It’s home to Hutchinson. Back in the 1960s, the Shankill, like many other loyalist areas in Northern Ireland, had its own “Tartan Gang”. Each gang had its own tartan “colours” – usually displayed as a scarf worn cravat-style or tied at the wrist. On the Shankill, the colours were the Stewart tartan. When Hutchinson joined he was just a teenager, on the path to taking part in the murder of two innocent civilians. Today, sitting at his desk speaking to The Herald on Sunday, Hutchinson is a bald, ascetically thin, 65-year-old espousing peace.

In Scotland, an old black-and-white picture of a long-haired teenager in flares wearing a tartan scarf would mean one thing – the Bay City Rollers. Not in Northern Ireland. It was

a mark of young men ready to commit violence. “This was way before the Bay City Rollers – they copied us,” Hutchinson jokes darkly. The memory sets him off on a long reflection about the shared history of the north of Ireland and Scotland. “My granny was an Ulster Scot,” he says. “There’s always been that connection … There’s a bond between people across the sea.”

Ulster Scots are mostly part of the Protestant community in Northern Ireland. They are often the descendants of the Scots who settled in Ulster on the orders of James I of England – James VI of Scotland – taking land from the old Gaelic nobility. Hutchinson’s grandmother, though, was a recent arrival – she was born in Scotland and made her home in west Belfast. People have been moving between the north of Ireland and Scotland for love and work for centuries.

Today, those connections are still evident, and at times uncomfortable and troubling –from the lingering sectarian animosity between some Rangers and Celtic fans, to Orange Order and Hibernian marches.

Contradictions

To many, Hutchinson will appear as something of a contradiction. He says he wants to confound “the stereotypes of loyalism”. A left-winger, he is now the leader of the Progressive Unionist Party – linked to the UVF in a similar fashion to the way that Sinn Fein is linked to the IRA. Yet Hutchinson has no time for one of the icons of Ulster loyalism – Ian Paisley, the fundamentalist preacher hated in his lifetime by the republican and Catholic community.

Hutchinson sees men like Paisley as “demagogues” who ramped up violence in the north. Metaphorically, Paisley “made the bullets and other people pulled the trigger”. Politicians like Paisley, Hutchinson says, “put ideas in people’s heads” which led to death and killing.

Nor does Hutchinson have any time for the idea of Empire – still a hangover among much of the loyalist community in Northern Ireland. “In the 1960s,” he says, “unionists couldn’t see that we’d moved away from the whole notion of ‘we are the Empire’ … they were still talking about Empire when we didn’t have one.”

Brexit violence

He is also strongly pro-Europe. Brexit has destabilised Northern Ireland dangerously. There has been violence of late, and security forces are worried. Hutchinson fears that without political leadership peace could be jeopardised.

“We have to learn from and understand the past,” he says, adding: “What I am calling for is for people to calm down.” The perception of Brexit undermining the “Britishness” of Northern Ireland is a potential catalyst for loyalist violence; and any border posts would be a potential target for Republican violence.

Threats have been issued against staff at Northern Ireland ports. Northern Ireland’s chief constable says the atmosphere in the north is “febrile” and has urged people to step back from the brink. There have been shootings over the last few months, including two gun attacks thought to be connected to loyalists in Coleraine, and the killing of a man in Belfast identified as a dissident republican this week.

“While there is a political vacuum there is an opportunity [for violence to return due to Brexit],” Hutchinson says. “We need to make sure we don’t allow that political vacuum to happen.”

On the risk of a return to violence in the north, he says: “We have a political framework and we need to work within that political framework … and for paramilitaries to remain within the peace process and not be diverted … The only thing that will divert people will be a vacuum – if politics isn’t working then people will say ‘we have to use the gun’, and that doesn’t matter if it is loyalists or republicans.

“So from my point of view the important bit is the political process is working and seen to be working.” In terms of violence, he says: “The threat is equal on both sides and we need to be careful.”

Although Hutchinson doesn’t believe there will be a United Ireland “within the next five years”, he warns that the result of any border poll would have to be handled with extreme care to avoid any return to the past. “No matter who wins that border poll there’s going to be a large minority – whether unionist or republican – so how do you deal with that large minority?”

He adds: “Irrespective of what happens in a border poll, we need to make sure that the people in this society go by politics. If unionism doesn’t give leadership… of course you could then have violence – the same thing could happen if republicans lost a border poll.”

With his memories of the breakdown of civil order in the 1960s and 1970s across Ulster – and his part in the ensuing terror and bloodshed – it’s the level of political leadership, and the tenor of debate, which Hutchinson believes matters most today.

Scottish independence

Scotland has clearly dealt with constitutional matters in a markedly different, and thoroughly peaceful way, compared to Ireland, both north and south, over the last century.

Hutchinson refers to the perception that the Government of Boris Johnson has undermined the union across the UK. He says: “I’m no Tory … but the one thing unionists expect is for the Conservative and Unionist Party to always want to retain the union.” There have been polls showing a majority of Tory Party members happy to sacrifice the union with Scotland and Northern Ireland on the altar of Brexit.

He says some of the recent debate around Scottish independence is worrying. He references comments made by the prominent SNP MP Joanna Cherry in early January. She said: “One hundred years ago, Irish independence came about not as a result of a referendum but as a result of a treaty negotiated between Irish parliamentarians and the British Government after nationalist MPs had won the majority of Irish seats in the 1918 General Election and withdrawn to form a provisional government in Dublin. While no-one wants to replicate the violence that preceded those negotiations, the Treaty is in legal and constitutional terms a clear precedent which shows that a constituent part of the UK can leave and become independent by a process of negotiation after a majority of pro-independence MPs win an election in that constituent part.”

For context, after the 1916 Easter Rising, Sinn Fein won a landslide electoral victory across much of Ireland in 1918 and declared independence. Eventually, the Irish War of Independence broke out in 1919, and ended in 1921. There were atrocities on both sides and around 2,000 people died. The Anglo-Irish Treaty brought the war, and British rule, to an end.

However, splits over the terms of the treaty led to the Irish Civil War – in which Irish Republican leader Michael Collins was assassinated by former IRA comrades. Northern Ireland also came into being.

Referencing Cherry’s comments about the Treaty, Hutchinson said he felt such analogies were “dangerous”, adding: “It’s a very bad example.”

Regarding Scottish unionists, he said Cherry’s comment “would send shivers down their back”.

He added: For those who know the history of Ireland, it’s a terrible thing. If we learned anything in Northern Ireland over the years it’s about the political language that you use … It’s different if they want to talk about William Wallace or something, but whenever you’re talking about something that was only 100 years ago, we certainly know the consequences of that … We need to watch all of this language … I’m appalled that a Scottish nationalist would use that as way of saying ‘this is the way to do it’.”

On the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the resulting Civil War between republicans, Hutchinson said: “Does she not realise that this divided families for years afterwards?” He added that while such comments would make unionists “pretty angry” it could also “split nationalists”, saying: “I don’t see how anything that happened in Ireland in the last 100 years is the way to deal with things.”

He also commented on a report in late January that Police Scotland were looking into comments made online in a pro-independence video where nationalists debated whether there will be a “confrontation between Scotland and England”. In a discussion about the possibility of English police being sent to Scotland to help deal with any civil disturbance, one said: “I’d happily sit there with a high-powered rifle and take them out.”

Hutchinson said: “It’s mad. These are people who haven’t a clue what they’re talking about. They think they understand what violence does to people or a country.”

The comments “send shivers up my spine”, he said, and came from “stupid fantasists”. Hutchinson said that British intelligence would infiltrate any groups involved in such discussions, but added that “Scotland is filled with law-abiding citizens who want nothing to do with this”. He said: “People who use this type of language need to be very careful what they are doing – it doesn’t need to be used in Scotland, it’s a peaceful country.”

Anyone invoking Ireland or Irish history, he said, should have a “hard look at what happened”. He also condemned online threats from loyalists in Scotland towards independence supporters. “It worries me,” he said. “Unionists must articulate their arguments about the notion of Scotland becoming detached from the rest of the UK … I want Scottish loyalists to learn from our experience … We need to be very careful … all of this can be done peacefully.”

Scotland and the Troubles

A LEGACY of the Ulster Troubles remains in Scotland to this day. Echoes of the conflict still reverberate, through sporadic but shameful episodes of low-level sectarianism. “In the west of Scotland,” says Hutchinson, “there’s division on a sectarian basis – maybe not as much as there is in Northern Ireland, but it’s still there.”

Scotland played a pivotal role in the Troubles. Both republican and loyalist terrorists chose mostly not to bring their “war” to Scotland. Due to historic, political and family connections, it was felt that murders and bombings on Scottish soil would backfire on both the IRA and UVF or UDA. Scotland provided a lot of low-level support for terror organisations in terms of fundraising, safe houses, gun-running, and recruits for paramilitary organisations of both sides.

Hutchinson returns to the ancient history of Dalriada, saying: “We were all one at one time, so from that point of view there’s always been a closeness … There’s no question that people in Scotland supported [paramilitaries on both sides] … Some came here, some went to prison – there are strong loyalist families in Scotland and they were prepared to help out with lots of things, and they did.” The same goes for republicans, he adds.

The future

Although Hutchinson has courted controversy and anger in the past by saying he has “no regrets” over his role in the Troubles, it might surprise many to discover that he’s sympathetic to republicans if not republicanism. He has built friendships with republicans. “I recognise that people on the opposite side to me were dedicated to what they did,” he says.

He accepts that the nationalist and Catholic community were not well treated by the Northern Ireland government before the Troubles began. “There was always going to be a backlash,” he says, adding: “What came first? The bad politics or the bad paramilitaries? The answer is easy.”

Despite the simmering tensions and recent violence in Northern Ireland, Hutchinson says he remains hopeful for the future.

Once again, he bucks against the perception of loyalists by saying that he wants politics in Northern Ireland to focus on issues like climate change, LGBT rights and poverty. He also says the north needs an “integrated education system” where Catholic and Protestant children “learn together”.

He talks of the “disgraceful” discrimination against LGBT people in Northern Ireland in the past. “Unionists are gay, unionists live in poverty, unionists need to go to foodbanks, unionists are transgender … We don’t live in the 1970s … For me it’s about people who are vulnerable around health and poverty and low-paid jobs … We’re in a different century now … We need to be clear that we are giving everyone in this society a chance.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel