What a lucky little sod I was to have David Jones as a childhood friend,” suggests Geoff MacCormack in his limited-edition book From Station To Station, a weighty tome that includes a candid collection of Bowie shots between 1973-1976.

During that time MacCormack was the singer’s constant companion. At the height of Ziggy Stardust’s success, he played the bongos as an auxiliary Spider From Mars for tours of Japan, America and the UK.

As a backing vocalist, he appeared on an exceptional run of albums including the groundbreaking Aladdin Sane (1973) and Station To Station (1976). Under the pseudonym Warren Peace he co-wrote Rock ’n’ Roll With Me from Diamond Dogs (1974) and joined Bowie on stage as a backing singer/dancer for the American Diamond Dogs Tour.

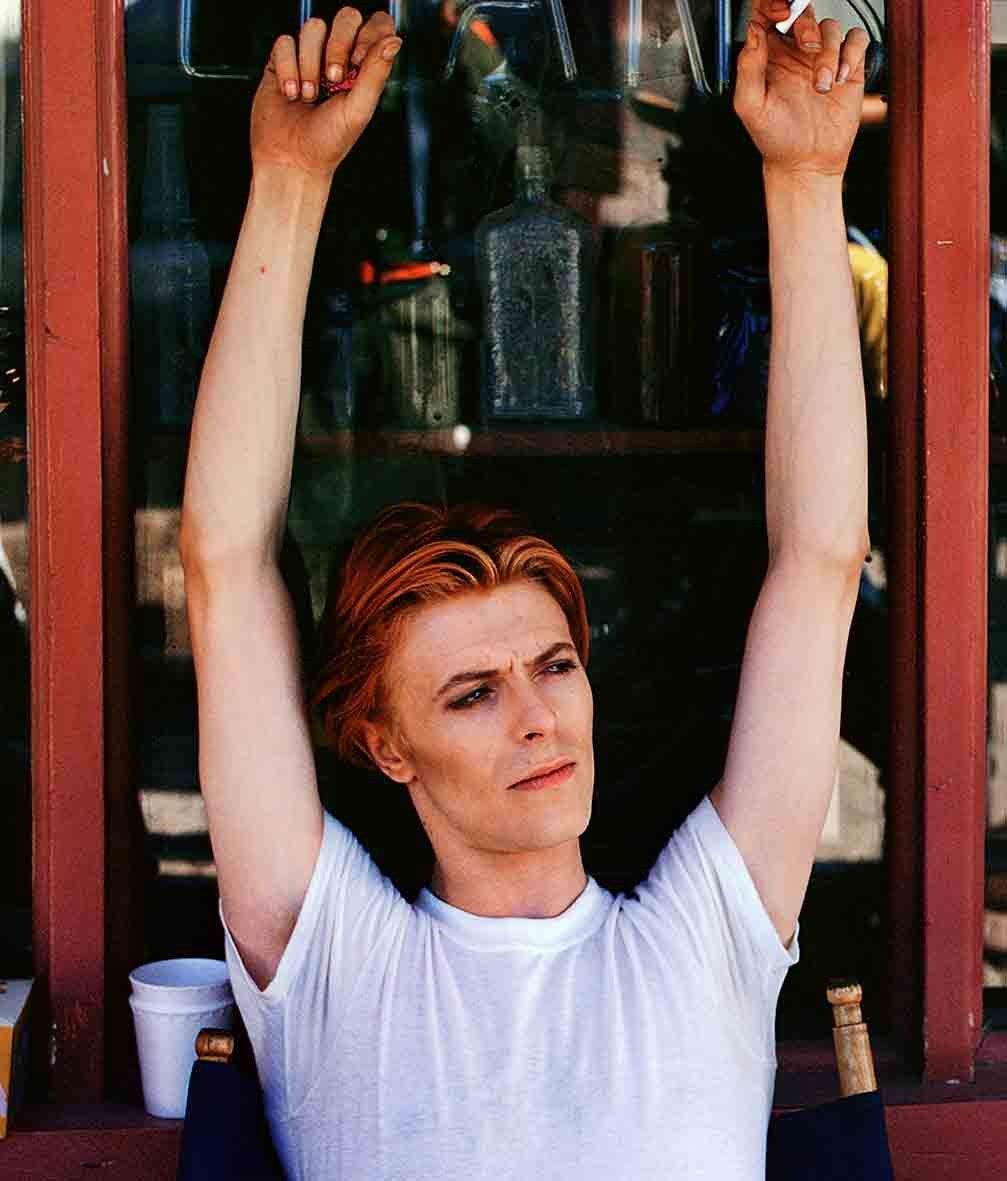

The flight-phobic Bowie would sail the Atlantic on ocean liners and cruise ships. When reaching his destination, tours would be completed only by rail and road. MacCormack was on hand to snap his subject throughout as well as a joining him on a trip across Russia on the Trans-Siberian Express and while filming The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976) in New Mexico. Many of those pictures feature in a new Bowie exhibition Rock ’n’ Roll With Me.

The current show in Brighton has suffered a broken-run due to covid, and MacCormack hopes to bring the spectacle to Edinburgh in the not too distant future. Although he got married in Glasgow, MacCormack admits he has not been to the capital since touring with Bowie in May 1973.

“I love Glasgow, I married my wife there 11 years ago but I’ve not been to Edinburgh since ’73 so the plan is to bring something more intimate up there; the show is a must for travelling.

“In 2018 the exhibition went to Russia which was daunting because when we visited the gallery it had these huge rooms, I wondered how we would fill it…we ended up running out of space.”

Rock ’n’ Roll With Me also features a rarely seen cinefilm shot by Bowie, The Long Way Home.

“It’s two halves of a whole” explains MacCormack. “In Japan, I bought a Nikkormat camera. It wasn’t cheap but it got me in on a basic level. The first picture I took was of David in front of the Trans Siberian Express with his hands on his hips, looking into the camera; it’s a very natural picture.

“David also had an 8mm cine-camera on which he documented our progress. The film has historic importance and I Iove the stuff that he filmed.”

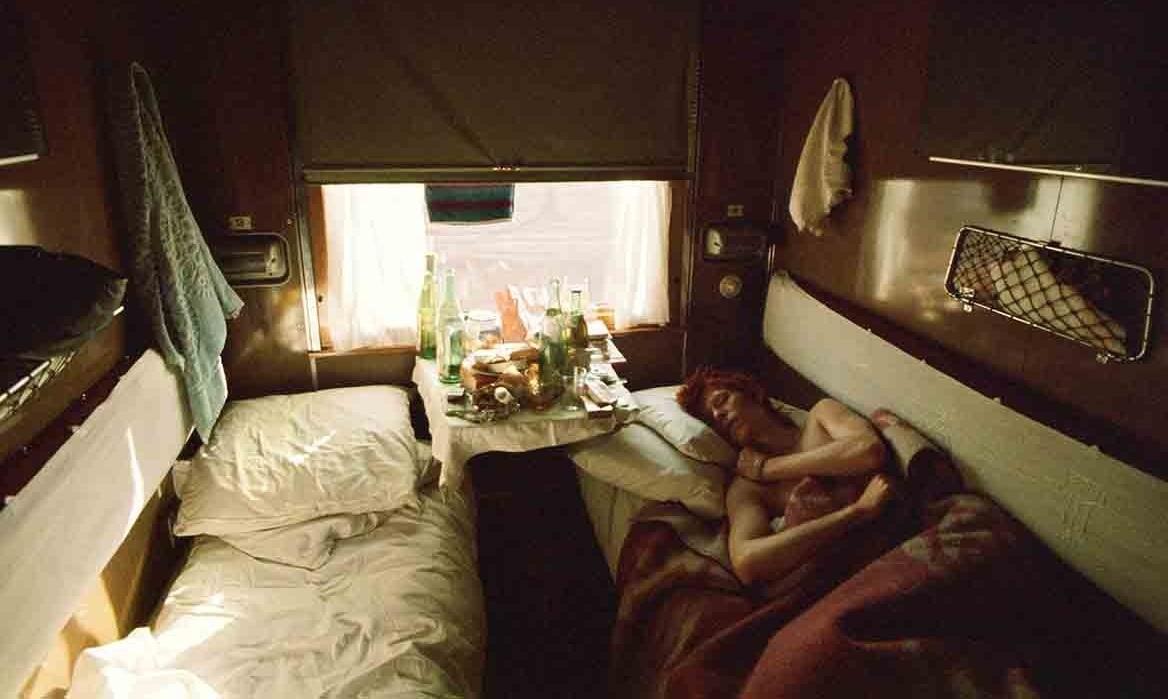

MacCormack also captured what he describes as “holiday-snaps” using a Kodak Instamatic. They include one involuntary image of Bowie asleep in his cabin, beneath a table of empty wine bottles after the pair spent the night drinking with Russian soldiers.

“He didn’t know I took that for 35 years,” says MacCormack who had kept the photos in a chest at his mum’s house. “Those snaps are like mobile phone pictures in a way, it’s the kind of stuff you might have on your phone and forget about. They are quite valuable because they narrate that period. There’s an intimacy because it wasn’t a conscious thing to whip out a camera. We have about 60 of those images in cases around the gallery that I took on tour.”

With their friendship stretching back to primary school age, singing in a local choir and attending Cubs in Bromley, it allowed MacCormack rare access and trust.

One recent exhibition poster features a sedate Bowie backstage shortly before he retired Ziggy, reading a newspaper. “That was the penultimate night at the Hammersmith Odeon,” MacCormack recalls.

“He’s reading a review from a time when they mattered. Everything was happening so fast and one thing led to another. I just happened to be around with the camera and used a zoom lens so as not to disturb him. I knew before he was retiring (the character) and I was amazed at how calm he was. There he is reading a newspaper like anyone does on a Sunday morning but he happens to be about to go on stage to do a complicated show. I wish I had taken more pictures but I didn’t want to push it because I wouldn’t have got access to David being so unguarded.”

The expense of processing the images was also a factor at the time, as MacCormack suggests, “there’s not yards and yards of film, you tended to make important decisions about what you were taking.”

He suggests that he could have done with the money at the time for the song he co-wrote with Bowie in October 1973. Rock ‘n’ Roll With Me was composed in Bowie’s Chelsea townhouse between the King’s Road and River Thames. MacCormack dropped in during a song-writing session and began a playful composition on an upright piano. Bowie arranged the verse and melody and ran it into a “killer chorus”.

Although the issue is now resolved, MacCormack didn’t receive a penny for the cut that appeared on Diamond Dogs and David Live in 1974 for many years.

“The management were legendary in their meanness towards musicians,” he explains. “There’s that story about the Spiders finding out they were on £75 a week while [pianist] Mike Garson was on $800. At the time I stated my name was Warren Peace which was probably a stupid idea, the management argued it was a pseudonym for David Bowie.”

Rock ’n’ Roll With Me was something of an outlier on Diamond Dogs pointing in the soul direction Bowie was about to take during the album’s American tour. It was a groundbreaking piece of rock theatre that included dance, mime and a choreographed street fight.

“The movements and routines were physically very demanding,” says MacCormack. “It was me, David and another dancer and backing vocalist Gui (Andrisano).

“The three of us worked hard and it was brilliant; it was one of the first pieces of rock theatre which had some kind of cohesion. It was a shame it never reached the UK.”

After recording most of Young Americans and stripping away the theatrics for a final leg of the tour Bowie was already moving on. In LA, MacCormack would have another songwriting dalliance with Bowie, this time being joined by Iggy Pop. Turn Blue would eventually appear on Iggy’s Berlin album Lust For Life in 1977.

Cocaine, a fascination with Nazi Germany, his failing marriage and an obsession with occult practice and writings had captured Bowie’s interest but his creative powers and aesthetic were arguably at their peak.

All this dark energy would be absorbed into Bowie’s next creation The Thin White Duke: the isolated, cold-blooded European alien who summoned a pre-pop atmosphere of neo-romanticism and a search for the arcane created a whirlpool of vitality on Station to Station.

The long-player remains Bowie’s most brilliantly strange and unfathomable work, even 45 years later. With his cocaine addiction at its peak, Station To Station’s creator had little memory of the recording and often approached any discussion of the time with caution and palpable unease. MacCormack remained alongside his childhood friend, providing the only other voice on Station To Station.

He describes it as “murder” having to finish the high-notes after Bowie lost his voice during the recording of Golden Years. MacCormack was also involved in the song’s arrangement: “the swooping gold phrase and adding wah, wah, wah on the end.”

He adds that, “they are cool things to have on your CV. David didn’t remember the Golden Years thing. We exchanged a few emails where I said: ‘Remember it was 40 years ago in the middle of the night and you were probably stoned.

“He said: ‘OK. You can have the wah, wah, wahs.”

MacCormack also captured snaps of Bowie recording the album at the Cherokee studio in LA where guests such as Rolling Stone Ron Wood dropped in. Although he admits they were images he can’t remember taking. Ultimately LA “wasn’t a good place to be” for him or Bowie.

MacCormack was offered opportunities through various eminent snappers of the time. Steve Shapiro, whose stills from The Man Who Fell To Earth that year provided album covers for Station To Station and Low “invited me to assist him in the middle of the 70s. I let him and myself down but ultimately it was a good thing because I came home and sorted myself out.”

In London Duffy, who had shot the Aladdin Sane sleeve and would work on two further Bowie album covers, suggested MacCormack could be his assistant “if I went to a colour lab for two years. My mouth said: ‘Yes’ but my brain said: ‘f***that’. I was interested in photography for five minutes; it just happened to be the right five minutes.”

Limited David Bowie prints and images by Geoff MacCormack are available at geoffmaccormack.com. A percentage of sales go to Cancer Research UK

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here