In the past year, as everyone's world has shrunk to encompass our immediate surroundings and the four sides of a two-dimensional screen, there seems to be a digital art revolution underway.

Galleries across the globe have thrown open their virtual doors to showcase art and artists, people who wouldn't have ventured inside a life drawing class for love or money are doing it online, while the late Bob Ross – hippy patron saint of happy trees, fluffy landscapes and fluffy clouds – has been jettisoned from online obscurity into the mainstream of BBC with his soothingly simple painting classes.

On Channel 4, Grayson's Art Club was a big hit during the first lockdown. It's now back in a peak Friday night slot. Grayson and his wife Philippa keep it simple with the couple making art in their home studio, while hanging out virtually with creative celebrities and members of the public.

Last Friday night, as Phillppa sewed "NURTURE" and "NATURE" onto a zesty cushion (the theme was "nature"), Grayson visited Reading Gaol, aka HM Prison Reading, to check out Banksy's latest work, a stencilled painting of a prisoner, resembling famous former inmate Oscar Wilde, escaping on a rope made of bedsheets tied to a typewriter. Banksy had posted a video online set to archive commentary from the sainted Bob Ross.

Back in the studio, in one of the most affecting pieces of television I've seen in years, Grayson spoke via video-conference to a young disabled woman called Becky Tyler, who made paintings using an eye-tracker on her computer. With his big dirty cackle, and direct unpatronising questions, Grayson drew Becky out of this awkward space. By the end of their conversation, she was giving him a tour of her personal gallery.

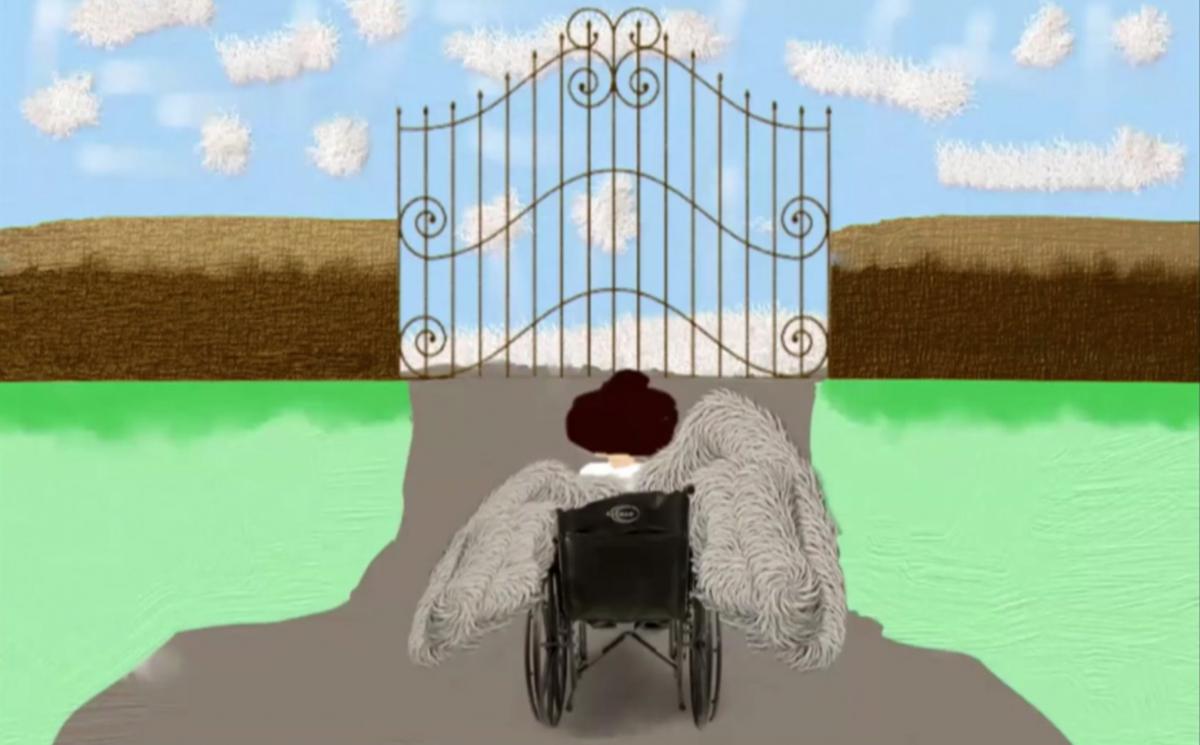

A digital painting appeared on the screen. It showed a figure in a wheelchair; its back to the viewer, wonky wings fluffed up with lush boa-like feathers. The figure is facing a set of closed ornamental gates. The sky is blue with fluffy white clouds; the grass uber-green.

"In my imagination," Becky told Grayson, "I can do so much more than my physical body can allow. For me, art means I can take part in creating pictures – the same as everyone else and I am not so limited by my disability."

After Becky had signed off, Grayson was visibly moved. "There it is," he said finally, "writ large. What art can do for you. That's what art is. It's about being able to affect the world with your thoughts and feelings."

The language of emotion is not something we use every day. When my artist friend, Sue Barclay, told me during a walk late last year that she'd started running an online course focusing on "integrating emotions" using art, the Scottish sceptic in me said "aye right".

But even sceptics are being challenged in this year of magical thinking. In early January, with a long period of featureless lockdown downtime stretching ahead, Sue sent me over information about her courses, which are based on the Dynamic Emotional Integration training of self-help author Karla McLaren.

McLaren has written several books, including The Language of Emotions: What Your Feelings Are Trying to Tell You and Embracing Anxiety. Sue, an award-winning painter, who has started making her own art again after a six-year hiatus, has been training with the US-based writer and educator for the last two years.

Sue's initial information asked basic questions. What are emotions, why do we have emotions and what are they for? Like most people in the last year, my own emotions have been heightened, but when I started to think about it, I couldn't pin down the actual emotions I felt, apart from in a vague "happy/sad" way. The deal-breaker for me however was the fact Sue uses drawing, or mark making, as she prefers to call it, to put her own stamp on the courses.

As she explains: "I always had trouble accessing my own emotions, let alone naming them. When I discovered Karla's Language of Emotions book around six years ago in a friend’s house, I was intrigued.

"It was the first time I'd read someone writing about emotions that made sense to me. I ended up making contact with Karla via her website and decided to do her Dynamic Emotional Integration (DEI) training. Finally, I started experimenting with art in my own DEI workshops.

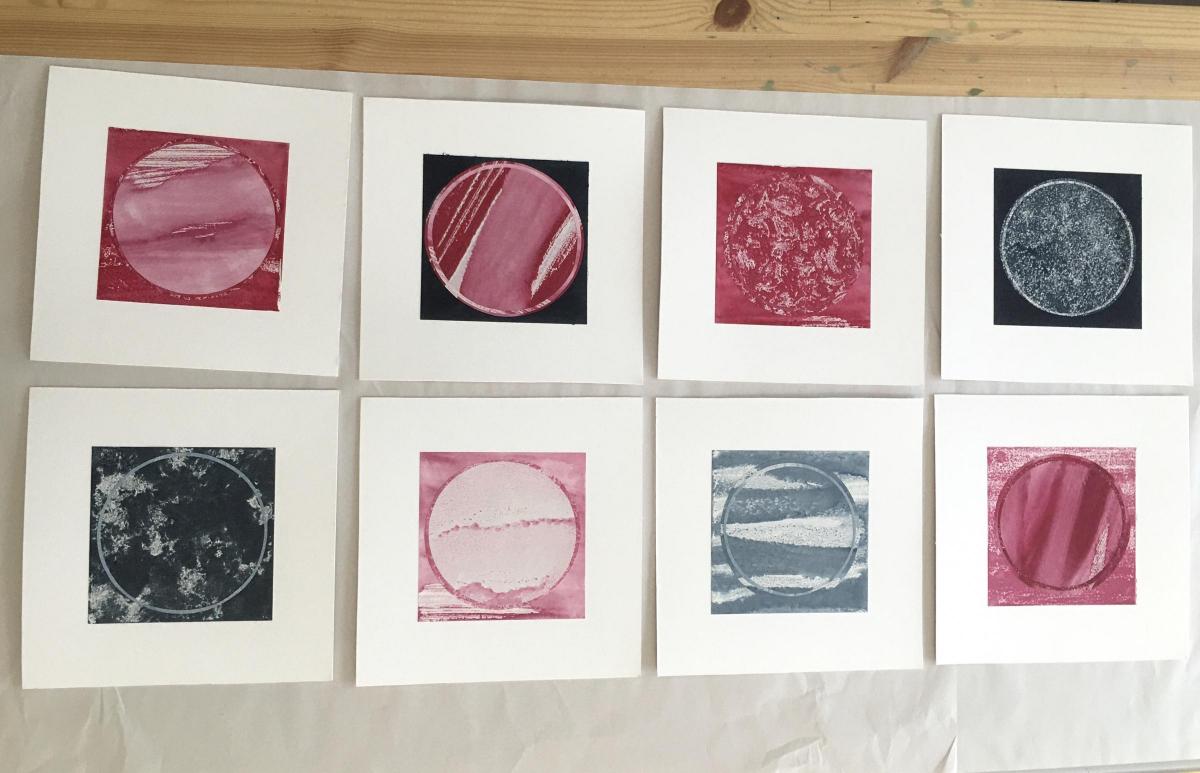

Having stopped painting as a professional full-time artist six years ago (as Sue Biazotti) and given up her studio to train as an Alexander Technique teacher, Sue suddenly had the urge to make her own art again. She's now busy creating a beautiful ongoing series called One World using acrylic paints and collage.

Inspired by art therapist Lucia Capacchione's theories about drawing and writing with the non-dominant hand as a way of connecting to our emotions and intuition, Sue uses this technique to encourage students to be less self-critical and more free-thinking.

Less self-critical, you say? I was in. I fished out a set of old oil pastels and sketchbooks given to me as hopeful gifts over the years and signed up for an eight-week block of two-hour long online workshops.

Sitting down with a bunch of virtual strangers on a Saturday morning talking about – and drawing emotions – took me out of myself in many ways. My mind was cast back to half-forgotten childhood patterns of basic emotions; anger, fear, sadness and happiness. It was liberating and at the same time astonishing to see what came into my head and onto the page. The green-eyed monster with a flower of envy… anyone?

As Sue points out, none of us receive much of an education in our emotions. "It tends to stop when we are five years old," she laughs. "Around the same time we start being self-conscious about making mistakes when we draw or paint!"

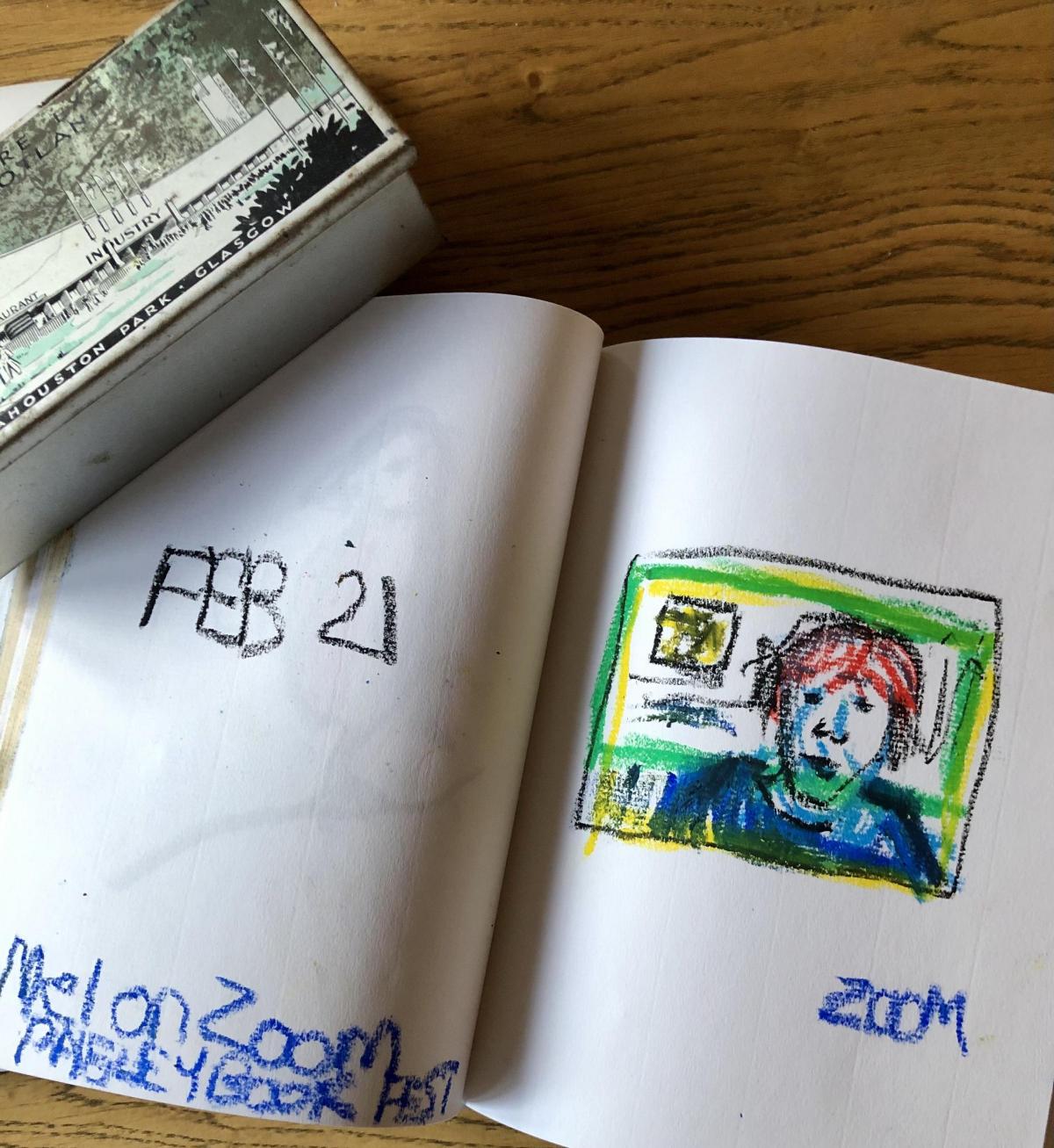

Although I write about art and think about it a lot, I had definitely touch with the part of me which messed around making marks on a page. Using my non-dominant left hand to draw and write gave me free rein to put crayon to paper. It was a revelation. As the weeks went on, my inner critic headed for the hills and I started to enjoy drawing again.

After each session, I felt like something inside me had decompressed. Tired but elated. At the start of February, I started doing a left-handed drawing a day with and half-way through March, I'm still at it. My inner critic has grown so blasé, she even allowed me to post a couple of drawings on Instagram. Then a journalist friend, Melanie Reid, wrote about a leftie Zoom portrait I sent to her in her Notebook column in The Times. People seem to like my wonky pastel drawings. Who knows where this emotional outpouring will end? You know something? It feels right.

For more information about Sue Barclay's Introduction to Dynamic Emotional Integration workshops and consulting visit: www.suebarclay.com &

To view Sue's work: https://www.instagram.com/suebarclayart/ & https://www.instagram.com/suebarclayworkshops/

Jan Patience on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/journojan/

Don't Miss

For many artists, having people rifling through their sketchbooks is akin to reading a diary or a journal. Intimate and fresh, drawings is a way of thinking out knotty forms, structures and problems.

Notes and studies become a library of information for future paintings. In a high-tech, digital world saturated by imagery, there are many artists for whom traditional drawing and sketching remains a vital discipline and part of their creative process.

Cyril Gerber's Drawing Show 2021, currently online for all to enjoy, includes drawings and sketches by a host of well-known names. Artists whose work is on show include; John Bellany, James Cowie, Colquhoun & MacBryde, Joan Eardley, The Scottish Colourists, Terry Frost, Peter Lanyon, William McCance, Margot Sandeman, Lara Scouller, Tom H. Shanks, Keith Vaughan and more.

There are around 60 drawings to savour. It's fascinating to note contrasts between artists like Joan Eardley, with her loose, intensely observed market scene in ink and pastel and her Hospitalfield tutor, James Cowie, with his controlled, yet half-finished watercolour still-life.

Terry Frost is known for his bright, saturated abstract paintings yet here, we see a different Frost sketching a harbour scene with nothing but a plain old pencil. In Keith Vaughan's Two Standing Figures in ink, there are marks which tell a story of an artist trying to resolve the puzzle of perspective and form. A surprisingly soft Peter Howson pastel drawing of a naked woman looks caught out in time while with a few deft lines, William McCance deftly magics up a snoozing cat.

Gorgeous soft lines from Helen Fay and Lara Scouller portray the animal kingdom in their own unique way; Fay via the discipline of etching and Scouller in pastel.

A treat for anyone who loves the free and easy nature of masters in the art of mark making.

The Drawing Show 2021, Cyril Gerber Fine Art, http://gerberfineart.co.uk/2014/the-drawing-show-2021-2/,

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here