EVER since Brexit, Prime Minister Boris Johnson has been at pains to tell a new story of the UK’s place in the world. Yesterday, Mr Johnson had what should have been his best opportunity yet to do just that when he outlined the Integrated Review of Britain’s defence, security and foreign policy, the biggest overhaul of its kind since the end of the Cold War.

Not that anyone of course wants to hark back to those frosty days of international diplomacy. That much Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab, was also at pains to make clear yesterday, when he warned against adopting a “Cold-War mentality” with China, the one country which if the review’s conclusions are anything to go by, Britain will be watching closely on the foreign policy front in the years ahead.

The review, or to give the document its official title, “Global Britain in a Competitive Age,” deals with many things, ranging from defence spending to counter terrorism and tackling climate change, but in its 100 or so pages you can’t help but notice the omnipresence of China at every turn.

Indeed, “China’s increasing power and international assertiveness,” is described in the review’s pages as the most significant geopolitical factor of the 2020s.”

So significant is Beijing’s assertiveness in fact, that Britain’s express aim, the review concludes, must be to expand UK influence among countries in the Indo-Pacific region in an effort to moderate China’s global dominance.

Biden talking the talk but not walking the walk on foreign policy

That, however, will be easier said than done and will take a lot more than the deployment of a British aircraft carrier in the region – as the UK government has announced – to rein in Beijing ambitions. Eye catching as such a headline might be, far more meaningful is the UK’s overtures about deepening its defence partnership with regional friendly powers like Australia and Japan.

But even then, the simple reality here is that while the UK might be a big player militarily in the Euro-Atlantic region, it’s a bit of a tiddler in the Indo- Pacific and no matter what it can throw in that regional direction it would have limited strategic value.

On the wider picture too, Britain is not only coming late to the challenge China presents, but even now in finally doing so, UK foreign policy remains riddled with contradictions.

Seen from Beijing’s perspective, these are changed days from those when late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping was fond of following the proverb “hide your strength, bide your time.”

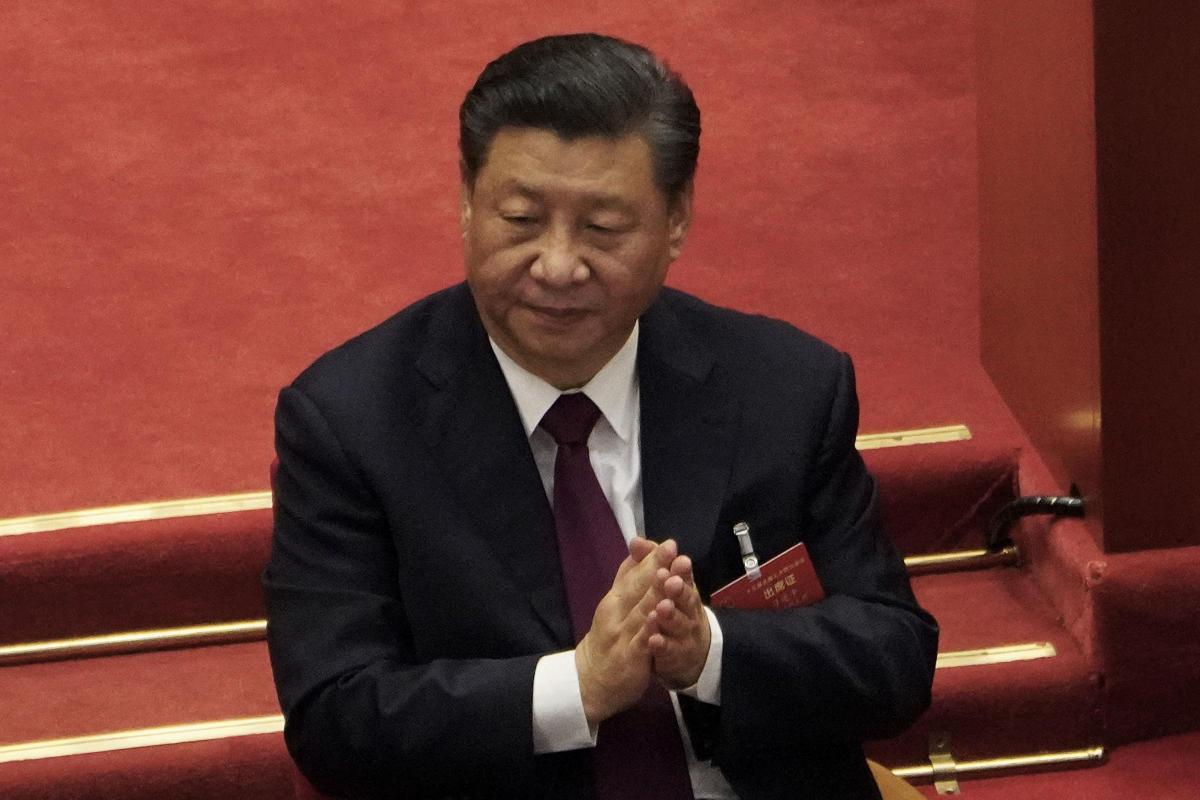

Under China’s current leader President Xi Jinping, it’s all been about open displays of assertiveness. Be it lashing out economically at Australia over Canberra’s questioning of China’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, bolstering its claims in the South China Sea, clashing with India in the Himalayas or flying warplanes in the Taiwan Strait, Beijing’s “wolf warrior” diplomacy has been making its mark.

All this too before the throwing down of the diplomatic and trade gauntlet by China to Britain. Beijing never hesitated in warning the UK government that it would “bear the consequences,” for excluding telecom giant Huawei from its 5G network.

And then of course there is the thorniest issue of all, China’s crackdown on the once semi-autonomous region of Hong Kong.

Not content with arresting pro-democracy activists and enacting a draconian National Security Law, Beijing has just proceeded to change the Hong Kong electoral system, which the UK government insists represents a major breach of the 1985 Sino-British Joint Declaration handover agreement.

Throughout all of this what then has been the response of Mr Johnson, who himself is a self-declared “fervent Sinophile?”

For if, as one would assume, a clear foreign policy as outlined in the review demands a clear China policy then the UK has shown precious little of that to date. Dominic Raab acknowledged as much yesterday saying that Britain’s attempts to influence Beijing had been marginal so far.

Other Tories are more open about their attitudes in handling Beijing. As The Economist magazine recently pointed out, “the Sino-sceptic coalition in Parliament is broad".

Tom Tugendhat, a leading China critic, is the liberal Tory chairman of the foreign affairs committee; Iain Duncan Smith, another, is a Brexit hardliner.

Admittedly, the diplomatic and trade line the UK government has to tread is a delicate one. At precisely the moment the UK seeks to define its role in the world outside the EU, engagement with China, the world’s soon-to-be largest economy was meant to be significant part of that future. But things could not be more sour between the two right now.

In the meantime, the EU has stolen some the UK’s thunder having late last year unveiled a long-awaited investment treaty that aims to open up lucrative new corporate markets albeit at the risk of antagonising human rights campaigners.

As Peter Watkins, Associate Fellow, at the International Security Programme at Chatham House, recently pointed out, Beijing’s behaviour has called into question the credibility of the official UK government line that China presents the UK with opportunities and risks that can be managed.

It’s all a bit like the diplomatic and trade equivalent of squaring the circle. That’s not to say it can’t be done to some degree, but little so far suggests UK foreign policy is up to the job.

Darkness is descending upon Myanmar

How, for example, can Mr Johnson’s government balance human rights commitments with trade and investment? What happens when you depend on China’s technology to deliver a green strategy? How do you talk mutual economic benefits when Hong Kong’s democratic structures are being dismantled?

Challenges like these apply not only of course to UK-China relations, it’s just that they happen to be a bit more complicated. Moreover, Mr Johnson to date has had an unerring gift for boxing himself into a corner when it comes to handling China and nothing in yesterday’s Integrated Review suggests any sure-footed strategy to escape that.

Ultimately too, Britain’s position is further complicated because of Washington’s stance in all of this. By far the western country with the most shares at stake in the Indo-Pacific will remain America, and it’s hard to see how President Biden’s administration will be anything but more explicit in its deterrence posture towards China.

Britain is far from alone among Western countries trying right now to recalibrate its relationship with China. But that preoccupation with a post-Brexit future must weigh heavily, and to date, UK policy remains riven with contradictions and anything but ‘integrated.’

Our columns are a platform for writers to express their opinions. They do not necessarily represent the views of The Herald

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel