THE first time I saw Roddy Frame perform live I was in very good company. His band, Aztec Camera, played one of their earliest gigs at The Bungalow Bar in Paisley on October 21, 1980. They’d been given the daunting task of opening for punk legends, The Revillos.

Initially, their volatile, hardcore following viewed Frame’s melodic, jangly guitar pop with suspicion. Also in the audience that night were several key figures in the Scottish music cognoscenti, keen to discover if they were about to see a genuine new talent or yet another post punk also-ran.

Frame’s sole focus was to impress the paying clientele with his songs. But standing in the packed venue, it was impossible to ignore Alan Horne, boss of Postcard Records, flanked by two artists from his label, Edwyn Collins of Orange Juice and Malcolm Ross of Josef K.

“I think we sent our first demo to everybody apart from Postcard,” revealed Frame.

“I’d read an interview with Alan in one of the music papers and thought: This guy hates everybody. He’s not going to be interested in us, so I’ll save myself the price of a stamp.”

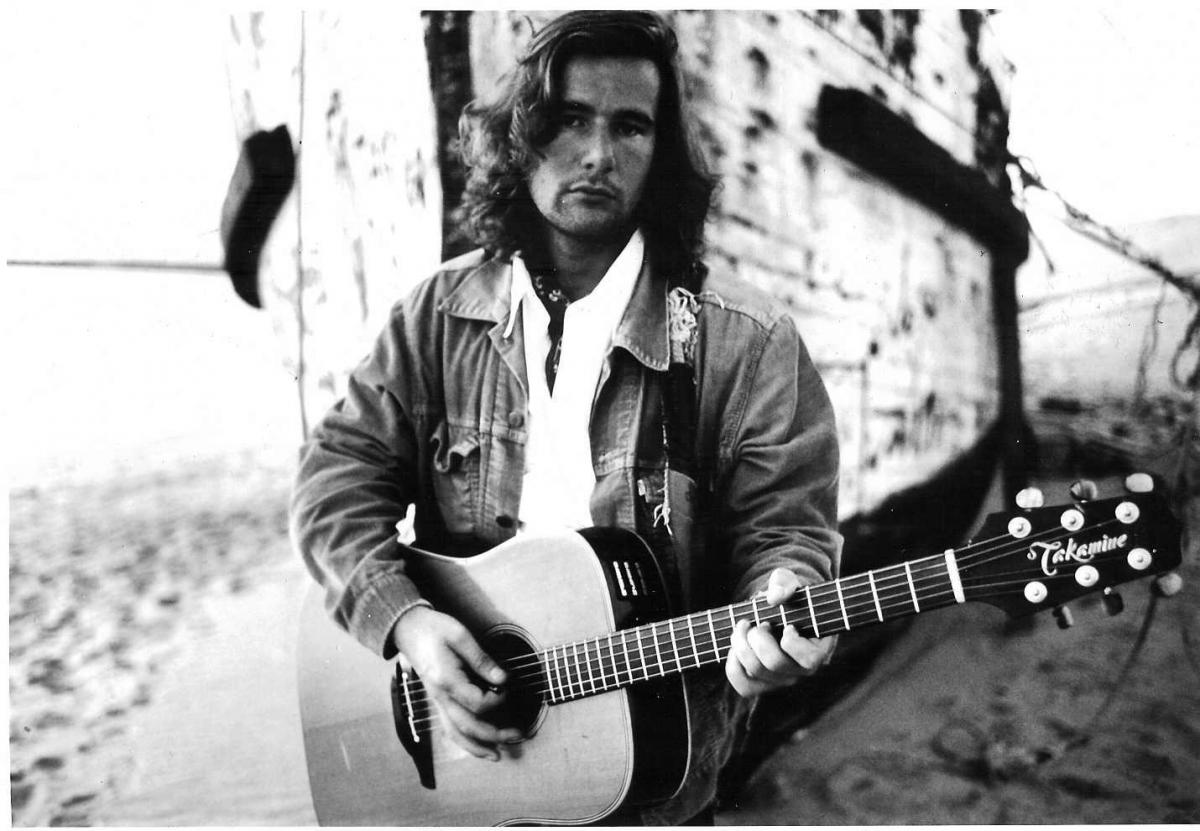

The band’s pivotal appearance is forever etched in my memory. With Frame on vocals and guitar, Campbell Owens on bass and David Mulholland on drums, they played a set built around songs demoed at Sirocco Studios in Kilmarnock. Frame – then just 16 years old – possessed a real lyrical flair, and had an assurance which set him apart.

READ MORE: The Pearlfishers: Up With The Larks – Scotland's favourite albums

“This was the gig where Alan was to decide if he was going to sign Aztec Camera to Postcard Records or not,” he recalled. “I wasn’t thinking much beyond the fact that there was him, Edwyn and Malcolm standing right in front of me, taking the p*** out of everyone, and making a real nuisance of themselves.

“Alan was magnetic. Because they were such big personalities it was hard to see beyond them.”

Aztec Camera were special. I wanted to find out more, and didn’t have long to wait. The band released their debut single, Just Like Gold, on Postcard, in March, 1981. It reached No10 in the UK indie charts. They followed up, five months later, with Mattress Of Wire, which climbed two places higher.

The sheer quality of the songs was a pointer for what lay ahead. The B-sides – We Could Send Letters, on the former, and Lost Outside The Tunnel – were later re-recorded to become key tracks on one of the greatest debut albums in Scottish rock history. The stunning songs on High Land, Hard Rain reflect Frame’s teenage years growing up in a council house in East Kilbride.

“They came together over the course of three years, between the ages of 15 and 18,” said Frame. “It’s a bit of a cliché, but from the minute I saw David Bowie on Top Of The Pops, that was all I wanted to do. I’d come home from school at lunchtime and play guitar. I’d be playing it again when I got back at four o’clock. I was compelled to do it, you couldn’t have stopped me. I was obsessed with music. So when the punk thing came along, it just further inspired me to start writing my own songs.

“I was into indie singles, and I think that’s why my own songs were all so short.”

Frame formed his first band Neutral Blue, with some school friends. Their set featured several Clash covers. But he was writing songs of his own, and moved things up a gear when he formed Aztec Camera. Roddy said: “You’d hear a record by a band from Manchester or Sheffield, and even when the whole Postcard thing happened in Glasgow, and think … they’re not that different from me. Maybe I could make a record too.

READ MORE: Billy Sloan on The Kevin McDermott Orchestra – Mother Nature’s Kitchen

“We rehearsed at The Key youth club in East Kilbride. I’d already written Lost Outside The Tunnel and a whole bunch of other songs. We made a demo at Sirocco Studios in Kilmarnock. We didn’t even have enough money to get back, so we had to walk home … wandering under the stars.”

Frame mailed the tape to a number of indie labels, including Zoo Records in Liverpool. “Zoo liked it and it got us a support with The Teardrop Explodes at The Bungalow Bar,” he recalled.

“I sent it to Factory Records too because I was a big fan of Joy Division, but they weren’t interested. I also got a very nice rejection slip from Geoff Travis at Rough Trade.”

But two years later, Travis did a U-turn and offered the band a deal, having been impressed by both Postcard singles.

High Land, Hard Rain – produced by John Brand and Bernie Clark – was recorded at ICC Studios, in Eastbourne.

Frame and Owens, were augmented by ex-Ruts’ drummer Dave Ruffy, who replaced Mulholland.

“We’d already done a couple of singles – Pillar To Post and Oblivious – with John and Bernie, so we felt very comfortable with them,” he recalled.

READ MORE: Billy Sloan: Associates’ ground-breaking debut was both baffling and beguiling

“John was a fantastic producer. He was into capturing what I wanted on tape. For the first time, I had somebody who said: ‘Why don’t you try this or try that?’ A lot of people who are 35 or 40 years old just don’t know how to handle somebody so young. But John was really on my level. It was all about the music.”

Frame’s “short songs” blueprint was strictly adhered to with most just over the three-minute mark.

The longest track, We Could Send Letters – with a duration of 5:43 – incorporated an extended guitar break which showcased Frame’s exceptional playing. It’s clear from the differing styles and textures on the album that Brand was more than willing to allow Frame to dictate the pace musically.

“John never saw me only being 18-years-old as a problem. So he let us be a bit more hands on,” said Frame.

“To his great credit, he went along with me. At that age, you’re still forming your identity … one day I’d be Dylan trying to sound like Tamla Motown, and the next I’d have my 12-string attempting to be The Byrds or Neil Young.

“I remember saying to him: ‘Have you heard Magazine?’ John had actually worked with the band, engineering Magic, Murder And The Weather. That was one of the main things that attracted me to him. He put enough trust in me, even at 18, to think … okay, let’s see where this thing goes. So the album was a real mishmash of influences. It certainly wasn’t a straight-ahead rock record. I think, that’s what made it interesting for him too.”

To raise the bar even more, Frame decided to use a different guitar on every track. “There were whole piles of guitars lying around and I was free to use whatever ones I wanted,” he recalled.

“There was a funny little Gibson I used on Back On Board, while for Release it was a big, fat Wes Montgomery Gibson jazz guitar.

“So, from that point of view, it’s amazing to think that there’s any continuity on the record at all. I also couldn’t make up my mind exactly what I wanted to be. I got a real kick out of mixing all my different influences in. But John managed, somehow, to knock it all into a serviceable whole.”

The album was brought to life by a striking sleeve designed by Glasgow artist David Band, who also worked with Altered Images and Spandau Ballet. Frame describes the trio of singles – Walk Out To Winter being the third – as “just like bursts of young energy”.

But when he focused on longer songs such as Back On Board, he saw the record really take shape.

“I remember thinking … this is starting to sound like an album now,” he revealed. “I had this idea of crossfading into Down The Dip while coming out of Back On Board. John very kindly said: ‘Okay, let’s try it’.

“It was the very last song I wrote and recorded. But that was exactly how I heard it in my head. Through all this confusion of different influences what it was really all about was … the song.

“Down The Dip is, just me and my guitar. It was kind of me saying: ‘I’m a songwriter and this is really what I’m all about … my words and my chords’. I thought it was a great way to end.”

THE Billy Sloan Show is on BBC Radio Scotland every Saturday at 10pm.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here