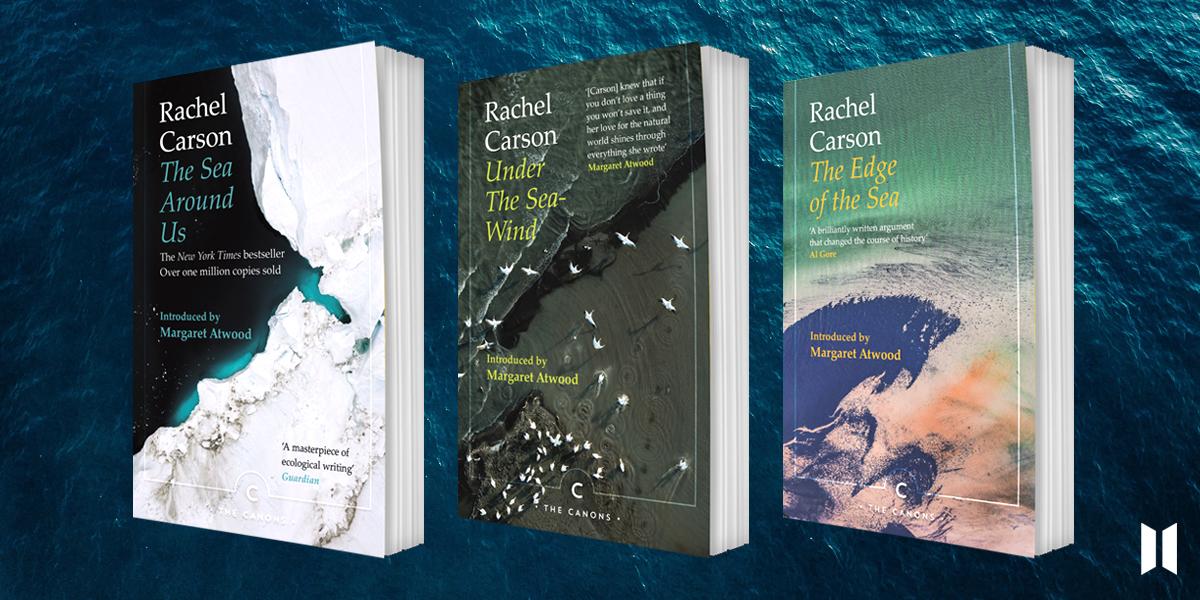

The Sea Around Us

Under The Sea Wind

The Edge Of The Sea

Rachel Carson

Canongate, £9.99

Review by Vicky Allan

“The beauty of the living world I was trying to save has always been uppermost in my mind,” Rachel Carson wrote just after the publication of Silent Spring in 1962. “That, and anger at the senseless, brutish things that were being done ... Now l can believe I have at least helped a little.”

Carson’s impassioned treatise on the damage done by pesticides would go on to change her home country of the United States and the world, triggering an environmental movement, spurring a congressional review and provoking a backlash from industry, which saw her labelled “hysterically overempathic” and communist, as well as an advocate of a “drift back to the dark ages where witchcraft and witches reign”, according to one critic.

Silent Spring was a labour of love for Carson, written while she was plagued by cancer and arguing that pesticides should be considered carcinogens. But it didn’t come out of nowhere in her own career as an author and scientist.

While many are aware of Silent Spring, fewer know that, prior to its writing, she was considered a poet of the sea, a storyteller of its science and history. Before she first observed the silence of the birds in pesticide-sprayed meadows, she had, while working as a marine biologist for the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, written another bestseller, The Sea Around Us – and it was anything but witchy. Rather, it was a powerful account of what was then known about the sea; a work that shifted with elegant ease between muscular and enlightening science writing and poetic nature writing.

Canongate has republished Carson’s sea trilogy, along with introductions by Margaret Atwood, and these allow us a glimpse of the work on which Silent Spring is grounded. What’s striking is that Carson is a keen observer of the interconnectedness of things. Under The Sea Wind (1941) creates vivid portraits of the lives of three animals: a mackerel, a sanderling and an eel. The Sea Around Us (1951) digs deep into what was known then about oceanic and planetary history, about geology, palaeontology, marine biology, and portrays an oceanic planet affected by sun and moon, with cycles and rhythms of tides, currents and winds, all impacting on each other. In The Edge of The Sea (1955), she creates an intimate depiction of a shoreline and the interconnectedness of life there.

This interrelation of living things was not a new idea. It was central to the developing discipline of ecology, what Carson had learned from her inspirational science teacher at Pennsylvania College and observed in her work as a marine biologist, a job that brought her face to face with the web of life. What Carson did, in her sea books, was to conjure, in words, portraits of that web.

Silent Spring may never have come into existence if Carson hadn’t spent those long hours at the shoreline, paddling in rockpools, or at her desk delving into papers on oceanic science. In the 1950s, she had bought a patch of land on a rocky promontory on Southport Island, Maine, and built a cottage there, which she would visit every summer. In The Edge Of The Sea, she magically describes a particular spot that has drawn her back again and again, “a pool hidden within a cave that one can visit only rarely and briefly when the lowest of the year’s low tides fall below it”. On one such visit she kneels down on “the wet carpet of sea moss” and looks back “into the dark cavern that held the pool in a shallow basin”.

These earlier books gave her the tools and knowledge to write her piercing call to action, Silent Spring. Though, in her sea trilogy there are only hints of the concerned campaigner she would become, for a 1961 edition of The Sea Around Us, she wrote a new introduction, which illustrates the development of her thought. In it, she attacks the disposal of radioactive waste in the oceans, saying, “the mistakes that are made now are made for all time”.

Such was the urgency of her feeling around the need to call out the dangers of pesticides, that even when she was plagued by “a whole catalogue of illnesses.”, she continued writing Silent Spring. “There would be no peace for me if I kept silent,” she once wrote.

Silent Spring had a seismic impact. In the years following its publication in the United States, a slew of acts would be passed: the Clean Air Act, the Wilderness Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act.

But the backlash against her at the time was profound and personal, and, as Margaret Atwood, notes in her introduction to the sea trilogy republications, distinctly misogynist. “She was a woman,” Atwood writes, “so was therefore stupid and hysterical.”

One letter to The New Yorker observed: “We can live without birds and animals, but, as the current market slump shows, we cannot live without business. As for insects, isn’t it just like a woman to be scared to death of a few little bugs! As long as we have the H-bomb everything will be OK.”

Such is Atwood’s sense of Carson’s significance that in her MaddAddam trilogy she has her green cult, God’s Gardeners, name Carson as one of its saints. For Atwood, Carson is a “pivotal” figure. “People thought one way before Silent Spring and they thought another way after,” she explains.

Carson died in 1964, aged 56. (A 2015 World Health Organisation review found that DDT poses cancer risks to humans, and highlighted the need for more effective public protections against dangerous pesticides.) She had never married or shown romantic interest in men, but had a very close and passionate friendship with her married neighbour at Southport Island, Dorothy Freeman.

Her sea series is not only fascinating for those with an interest in the prehistory of Silent Spring. There is much to marvel at in their pages. The Edge Of The Sea is a book to take down to the beach and rockpools – I will pack it in my own bag for the summer holidays.

But what strikes me most, as a retrospective reader, is that these books seem like scenes set for a coming disaster of the seas, not yet apparent in Carson’s lifetime. Since then, the ocean has had its own silent springs – collapsed cod stocks, the bleaching of the coral, missing salmon, seabeds destroyed by dredging, microplastic pollution, the floating garbage patches.

The author would have been horrified to see what has happened to the sea since her death. Were she writing now, The Sea Around Us would be quite a different tale. No doubt, like Silent Spring, it would be a controlled, carefully researched howl of rage.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel