The Black Ridge: Amongst the Cuillin of Skye

Simon Ingram

William Collins, £20.

Review by Cameron McNeish

In 2000 John MacLeod of MacLeod, Chief of the Clan MacLeod put the Cuillin of Skye on the open market at an asking price of £10 million. He never did get a sale. Some said the mountain range was priceless and the more pragmatic reckoned the Cuillin was worthless – there was little farming or crofting activity and no sporting income, just a pile of rock and scree. However, the proposed sale did create a much-needed debate about land ownership in Scotland, and at the centre of that debate was the question of the worth of mountains.

During the debate it was even suggested that if we insist on defining such mountains as the Skye Cuillin by outright ownership then surely, by right of usage, by habitual resort, by unchallenged possession, by moral justification, if these mountains of the Cuillin belong to anyone, they belong to the mountaineering fraternity of the world. By the same token, the indigenous Gaelic population of Skye could make a similar claim to such moral ownership. Didn’t their bard, the late Sorley MacLean, describe these Cuillin hills as the “mother-breasts of the world, erect with the universe’s concupiscence?” Here lies the very heart of Gaeldom, “the white felicity of the high-towered mountains”, beckoning the Gaels to their homeland.

According to Meg Bateman, a MacLean scholar and a lecturer at Sabhal Mor Ostaig, Skye’s Gaelic medium college, “it’s the landscape that gives form and sensuousness to MacLean’s ideas and lets him communicate them as emotion”. In An Cuillin, for example, the mountains appear as many different things but essentially the poem traces man’s oppression of man, particularly in the context of the Highland Clearances. The ghosts of the perpetrators of the Clearances appear in a demonic dance, perched on the pinnacles. The cries of the people leaving the land are heard.

The Cuillin responds, rocking and shrieking. Later, the Cuillin takes on the embodiment of a castrated stallion and the bogs in the glens below represent the spreading of corruption throughout the world. It’s heavy stuff, but eventually the human spirit prevails and men gather on the hill to witness the Cuillin taking on the form of a stag, a lion, a dragon an finally an eagle. A triumphant finale. Human dignity rises over adversity, part of the socialist dream that MacLean believed in so fervently. The Cuillin rises, as MacLean writes, on the other side of sorrow.

“Who is this, who is this in the night of the heart?

It is the thing that is not reached

The ghost seen by the soul

A Cuillin rising over the sea”.

It’s hard to deny the permanence of the mountains, their steadfastness, their ever-presence, looming over the conceits of man whether in the bloody clan battles or the intolerance and viciousness of the Clearances. MacLean taps into that awareness of longevity and portrays the mountains as a symbol of triumph.

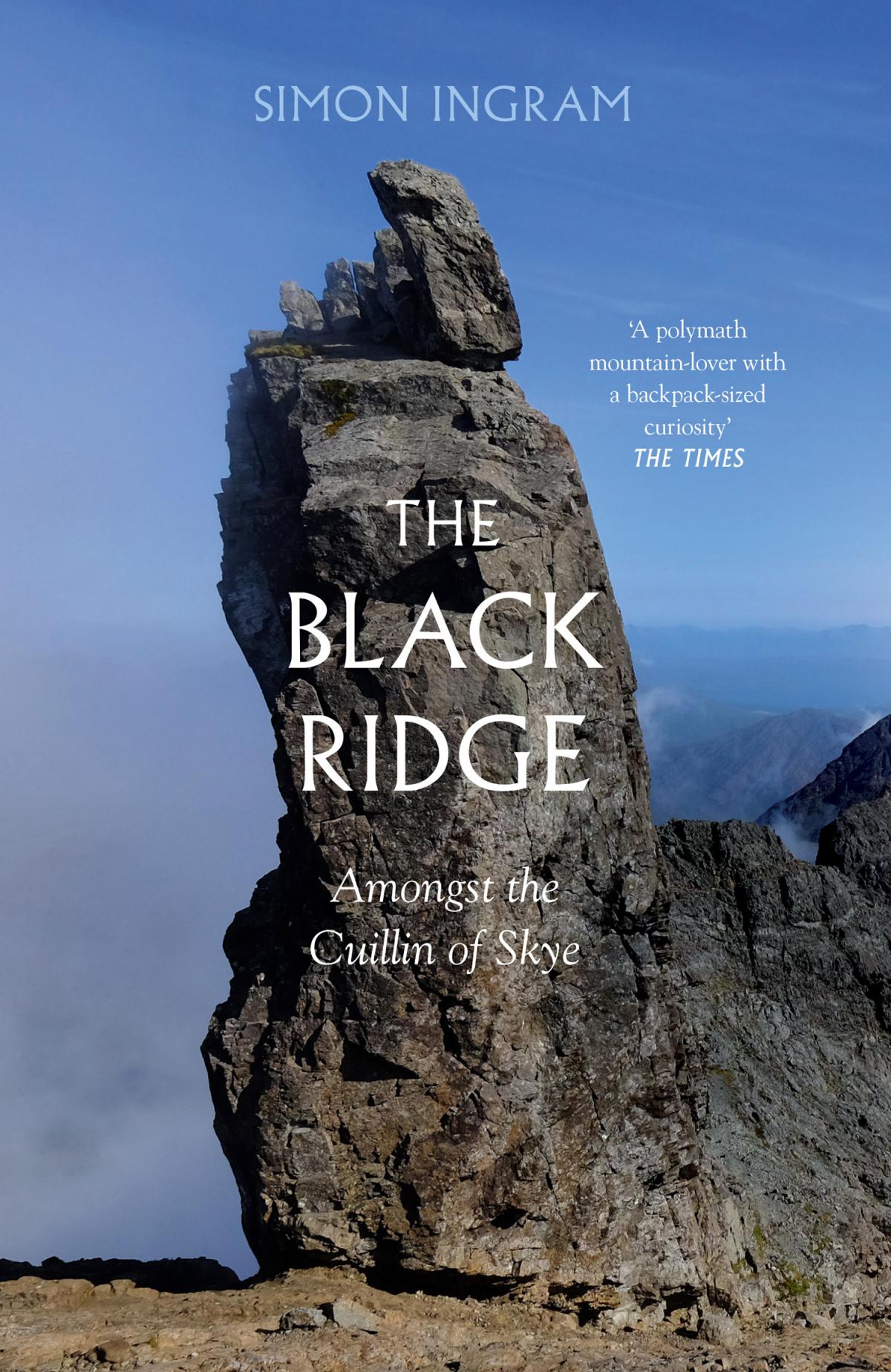

In his wonderful tome (565 pages of it) of a book, The Black Ridge: Amongst the Cuillin of Skye, author Simon Ingram arrays history, geology, weather and folklore around his own personal triumph: the traverse of the narrow, sinuous ridges and mountain-tops that make up the Cuillin Ridge. Perhaps "triumph" is the wrong word because there is little here of the chest-beating triumphalism that is so common in contemporary mountain writing.

Instead we have a beautifully written treatise of a long-distance fascination with a mountain range, a love affair that’s tinged and tempered with concern and hesitation, fear and apprehension. Simon Ingram, by his own admission, is no hard-nosed climber, but an enthusiastic hill-walker with an acute awareness of his own frailties when it comes to narrow, sinuous ridges and vertiginous cliffs and crags, the very antithesis of his home landscapes of flatland Lincolnshire.

The history of mountaineering in the Cuillin (for that’s what it is, these are not "hillwalkers' hills") is peppered with tales of derring-do and bold, exploratory climbing and the area’s pre-history evokes images similar to Sorley MacLean’s emotions, a fractured, pinnacled, mist-obscured landscape of Ossian, Fionn MacCumhail, Cuchulain and Scathach, the warrior queen who trained the greatest heroes of all. Later came the artists and the poets, the priests and the mystics, the wanderers and the lost, all with their own stories to tell of a tiny corner of western Scotland that was, until relatively recently, terra incognito.

No other mountain range in the UK boasts peaks that are named after the mountaineering pioneers of the late 19th century. The Cuillin is unique on so many levels, a miniscule mountain range in world terms but one that has captured the hearts of so many.

The Skye Cuillin has obviously captured Simon Ingram’s heart and that fact resounds from every page, but this is no masochistic, chauvinist affair. The author has eased himself gently into his experience of the Cuillin, a slow process but one that has allowed a gentle assimilation of all the Cuillin has to offer: romanticism, folklore, history, geomorphology and of course, challenge.

So many hillwalkers, especially the baggers, throw themselves at these big, complex mountains as though to get the experience over quickly, to bag the summits, get the selfie, and be gone before their luck or energy runs out. Instead, Simon Ingram wooed these peaks and pinnacles with consideration and care, over several visits to the ridge’s outlying features to familiarise himself, test himself, and spent several years researching and learning about every aspect of the Cuillin imaginable. And these Ossianic efforts paid off, perhaps not in his experience of climbing the peaks of the Cuillin Ridge – he did experience various difficulties and issues – but in the compilation of what will undoubtedly become a classic narrative of this scenically magnificent, legend-rich and geologically unique part of Scotland.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here