IT was an unprecedented move and was one of the major changes for women in the services, but when the second National Service Act was passed in 1941 it paved the way for female conscription.

While women had played their part during the war effort during the 1914 to 1918 world conflict, they had never been conscripted.

In 1940, a secret report by Sir William Beveridge demonstrated that the conscription of women, as well as of men, was unavoidable.

Read more: Bravery of Victoria Cross hero who was last man standing on battlefield remembered 75 years on

From spring 1941, every woman in Britain aged 18 to 60-years-old had to be registered, and their family occupations were recorded. Each was interviewed, and required to choose from a range of jobs, although it was emphasised that women would not be required to bear arms.

And on December 8, 1941 the National Service Act (No 2) came into effect with women being conscripted for the first and only time and this week marks the 80th anniversary since the first women were conscripted.

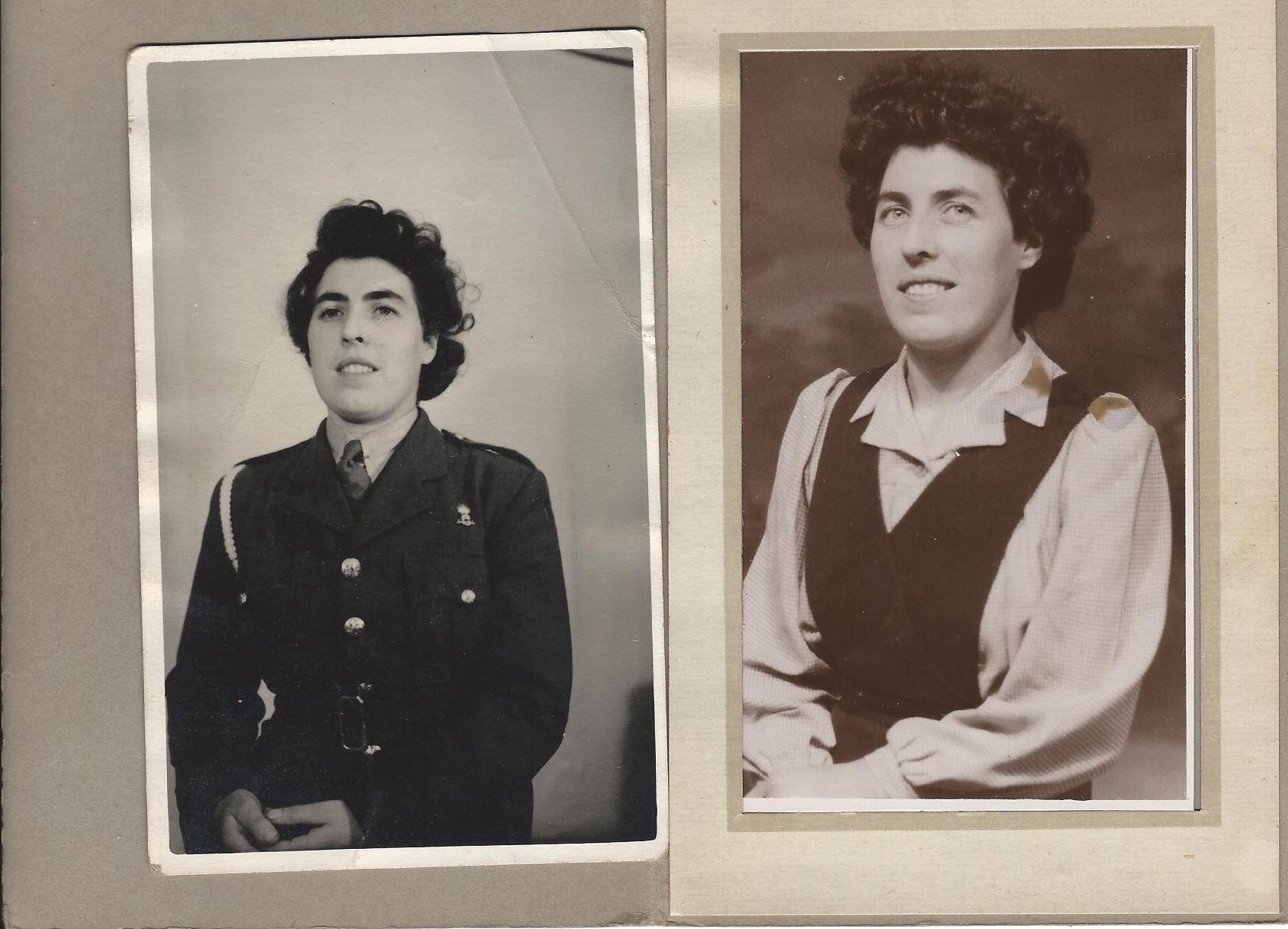

Scot Helen Jewitt was conscripted in 1942

To begin with only childless widows and single women 20 to 30-years-old were called up, but later the age limit was expanded to 19 to 43, 50 for First World War veterans.

The WRNS, having been disbanded at the end of the First World War, were reformed in April 1939. WRNS were posted to every home and overseas naval unit. There were 72,000 serving WRNS in 1945.

Another service disbanded after 1918 was the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corp WAAC), they were reformed as the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS). More than 250,000 women served in the ATS during the Second World War, making it the largest of the women’s services.

Read more: Hampden site: Kick off for historic ground's Unesco world heritage bid

As part of the conscription requirement women had to choose whether to enter the armed forces or work in farming or industry. By December 1943 one in three factory workers was female and they were building planes, tanks, guns and making bullets needed for the war.

For 103-year-old Helen Jewitt the anniversary on Wednesday is extremely poignant as just two months after the first female conscriptions, she too found herself being called up and her life changing forever.

Originally from Hamilton, South Lanarkshire, Mrs Jewitt initially went to Edinburgh for training, then to Aldershot, and London, west to Ty Croes in North Wales, east to Frinton on Sea, and finally to York.

Scot Helen Jewitt was conscripted in 1942

As a cook, she was part of a team which fulfilled the saying ‘an army marches on its stomach’.

Demobbed at the end of the war, she married the military policeman she had met during her time in service. While it might be 80 years ago, Mrs Jewitt still recalls her wartime exploits from dirty dishes to being one of the first British people to see the diagrams of the infamous doodlebug.

At the beginning of the Second World War, the young woman worked as a butcher in her local shop and knew that having a ‘man’s job’ meant she was exempt from serving. However, when she received her call-up papers for national service in 1942, she chose to tell them she was merely an assistant which meant that she was accepted.

Mrs Jewitt recalled: “I arrived in Edinburgh for basic training, sleeping on a bunk bed in a billet with 13 other girls. Learning to march was daunting, not least because as an eight-year-old girl, I had had an operation on one leg leaving it two inches shorter than the other. In order to ‘about turn’ we were taught to put one foot behind the other, but this caused me to tip over!”

Realising there was a problem, her sergeant arranged for her to have one shoe built up on the sole – a great solution for marching, but her footwear was soon to change when trades were assigned.

Having completed basic training the girls were asked for their preferred trade. Mrs Jewitt was keen to be a driver but when she put her name forward was surprised to be asked about her licence. Thinking they would teach her to drive she was disappointed to find that this was not an option and instead she was dispatched to Aldershot for cooks training.

“I had spent some time in domestic service, and with butchering experience, I found the work easy, and with 20 cooks working together at any one time I enjoyed being in the kitchens – even the clogs we had to wear on our feet,” she added. “After a day of cooking, we would attend lectures in the evenings in the still hot cookhouse, where it was difficult to stay awake.”

This is where young Helen Tocher, as she was known then, excelled and learned to cook for large numbers, and on special stoves under canvas cover, and as shift leader earned herself promotion to Lance Corporal.

During the course of three years she travelled to different camps around the UK, the women being assigned depending on the ratio of support services needed for the men in training. From Aldershot, she was sent to London to join a battery of the 78th Anti-Aircraft Regiment of the Royal Artillery. Finding herself more city-wise than some of the country girls she adapted well, even managing to get one girl to board an underground train despite her great fears and refusal to board.

Mrs Jewitt added: “We moved around to support the men learning to fire weaponry and we went to Ty Croes so they could shoot over the Irish Sea, Walton-on-the-Naze, Essex, to shoot towards the Netherlands, and up to Whitby Abbey to aim into the North Sea.

“We were at Hilly Fields in Brockley when I remember watching one day as a Nazi fighter pilot was hedge-hopping so low that I could clearly see his face. Here there were Ack Ack guns and barrage balloons, and I remember taking cocoa to the officers during night raids.”

Shortly after D Day in 1944, the Battery to which she was attached was posted to Belgium and she was looking forward to joining them, but developed dermatitis on her hands which was attributed to working with water. As this was essential for a cook, the Battery left Britain without her, and she stayed behind to help in the offices.

While she might have missed out on the posting to Europe, moving on to her next base, Frinton On Sea, the threat of danger still loomed over them as they went out their work.

“I remember the doodlebugs overhead and waiting to hear the engine cut out before running for shelter,” she said. “One day a messenger arrived with some plans and an officer called me into his office and showed me a diagram of a doodlebug. This was the first time the British had any information on the bomb.”

Towards the end of her time in the ATS, she was posted to York to work in stores. Here she was tasked with clothing the men who were being demobbed, learning to guess their sizes by eye, and collecting in all their old uniforms – they were allowed to keep only their underwear. Although she chatted with the men, they never talked about their experiences of the war, they were too sad. She remembered one man who had been shot down the back of his head and had severely restricted movement.

While being conscripted meant being away from her family in Lanarkshire for long periods of time, when the end of the war came there was time to let their hair down.

Mrs Jewitt added: “We did have good times in York meeting people from all around the world in the NAAFI, the Free French, Poles and Canadians.”

For Mrs Jewitt it was a more local lad who caught her eye. Denis Jewitt was a military policeman from Middlesbrough and also a conscript having been in a protected profession. Playing cards in the NAAFI one night they spotted the distinctive Red Cap and scrambled to hide their cards but he saw everything. They got talking, and kept in touch when he was posted to Africa. On his return they married and went on to have five children. One of her daughters went on to join the WRNS and her family remain extremely proud of her service career.

“I would have liked to have stayed on, but I was demobbed in 1946,” she added. “I do feel women should have better recognition for their service, and my message to any young women joining today’s army is enjoy yourselves..”

Mrs Jewitt is a member of the WRAC Association, the national military charity which supports women who served in the ATS and Women’s Royal Army Corps. Women of all ages, ranks and experience come together to share their stories and experience the camaraderie they once felt within their Corps, whether they meet in person through the various branches and interest groups across the UK, or enjoy phone contact, benevolence support or the Association magazine. The WRAC Association also works to highlight the disadvantages some women experience to this day as a result if their service. If you or someone you know would benefit from knowing more about the WRAC Association, visit wraca.org.uk.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel