THE Average White Band knew it was going to take a lot to impress Jerry Wexler. Would a giant of the US record industry be interested in their brand of Scottish soul and funk?

Wexler had worked with the greats, producing acclaimed albums by Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles and Otis Redding. He’d even coined the phrase “rhythm and blues”.

But the group, who’d been dumped by their record label, were confident that if he heard their songs they’d win him over.

“It was a huge roll of the dice – the ultimate gamble – but we had nowhere else to go,” recalled AWB vocalist/guitarist Hamish Stuart.

“We went for it simply because we thought Jerry might like our songs. And he did.”

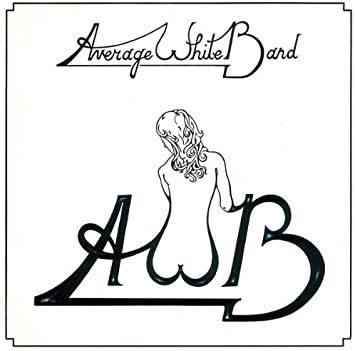

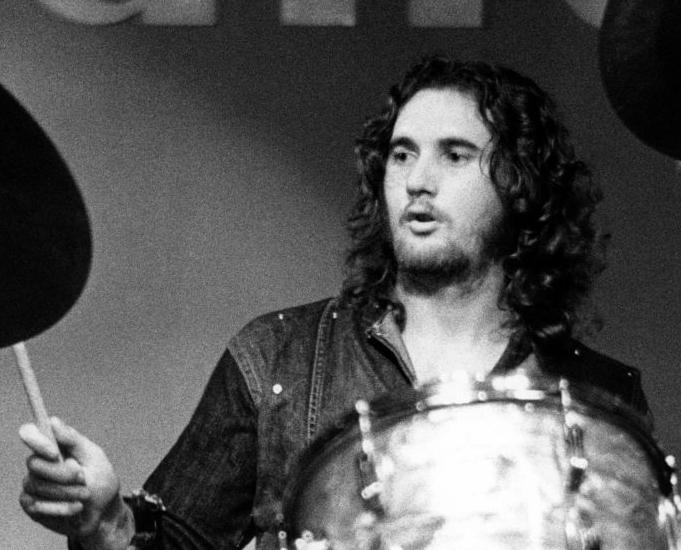

Their gut feeling paid off. Two years later, they were No. 1 in the US Billboard Hot 100 albums and singles charts. But their road to that unique achievement had proved problematic. The band were formed by Alan Gorrie (vocals/bass) and Malcolm “Molly” Duncan (saxophone) in 1972. They soon settled on what is regarded as the classic AWB line-up with Stuart, Onnie McIntyre (guitar), Roger Ball (keyboards) and Robbie McIntosh (drums).

The group got their first break when supporting Eric Clapton on his “comeback concert” at the Rainbow Theatre in London the following year.

They were signed by MCA, but while their debut album Show Your Hand was well received, sales were poor.

“We told MCA, we want to make our next record in America. We thought it would give our music a bit more authenticity,” revealed Hamish.

“They said, isn’t that a bit like taking coals to Newcastle? Which didn’t go down well.”

Bruce McCaskill, who’d worked with Clapton, became their manager. He had a reputation for “making things happen”, and so it proved when they hit US soil.

“We had a good relationship with Karen Shearer, the publicist for MCA in Los Angeles,” said Hamish.

“She offered to lend us her house in the Hollywood Hills to work in. Karen moved out and we moved in. We put blankets over the windows and wrote new songs in her living room. We worked really hard and all the music began to come together. Bruce sold his car so we could add to the budget a little bit. Somehow we managed to scrape enough money together to exist.”

The band booked into Clover Studios and recorded material for their second album.

“Most of the real writing was done at Clover. Ultimately it fell to me and Alan to come up with the lyrics,” he said.

“I had an idea for Person To Person but couldn’t come up with anything other than the title and the theme which was those long distance calls you make when you’re on the road. So Alan wrote the verses and we refined them a little. Everybody would chip in. The first time I sang the vocal we came up with the melody on the spot.

“Musically, the real groundwork was done at Clover. We were very happy with what we’d got.”

But when they played the tapes to Arty Mogull, head of MCA in Los Angeles, they reached a crossroads.

“We all sat in his office as he listened to the album. Then he said … Look guys, I really don’t know what I can do with this. Take your tapes. You’re free to go,” recalled Hamish.

“We had an inkling he might be underwhelmed by what we’d done. But we had an ace up our sleeves.”

McCaskill had learned that Jerry Wexler – a partner in Atlantic Records – was going for dinner at the home of a mutual friend. “As soon as we got out of the meeting we drove over to Laurel Canyon and crashed the party. We had nothing to lose,” revealed Hamish.

“We played the tape to Jerry and he thought the songs were great but said … I can hear what’s there, but it could be so much better.

“Ahmet Ertegun, founder of Atlantic, had seen us playing with Clapton, which was a big shop window for us. Slowly people in the industry were getting to know about us.

“Jerry was interested – and inquisitive enough – to see if we were the real deal.

“But he wanted to re-record everything with his production team. It was a done deal. We couldn’t believe it. We came flying out of the party and headed to the nearest bar to celebrate. We realised this was a new beginning.”

Within weeks, the band began working in Criteria Studios in Miami with the Atlantic Records’ production “dream team” of Wexler, Tom Dowd and Arif Mardin.

“We walked in and there was Aretha Franklin sitting at the piano playing with a band of the top session musicians,” said Hamish.

“It was THE most jaw dropping moment I’ve ever experienced. We spent the next three days deciding which one of them would produce us. Ultimately it fell to Arif. They felt he was the right man for the job.”

The album was recorded by Mardin on familiar territory … the famous Atlantic Records Studio at 1841 Broadway in New York. Within days of starting working with the producer – who became a multi-award winning Grammy winner – the band realised they’d moved up a gear.

“There was such a great level of acceptance towards us from everybody who came on board,” recalled Hamish.

“Arif was instrumental in really helping us develop new ideas. We knew we had good songs. But I don’t think I ever felt we were out of our depth. It was more a case of, wow, this is amazing.

“We re-recorded most of the songs and there were a couple of new additions. We also re-thought Pick Up The Pieces. It had a completely different feel from the original. In the time between Clover and Atlantic we were really developing. The new groove we discovered is the one which is still around.”

At the end of the sessions, the band returned to Scotland leaving Mardin to mix the tracks.

“The cost of keeping six guys in New York – hotels, food and other expenses – was mounting up,” said Hamish.

“But we were riding the crest of a wave with Atlantic. We totally trusted Arif and knew we were in safe hands.

“We were knocked out when we heard the finished product. The songs from the Clover sessions were pretty dry – we didn’t have a lot of reverb or echo – but that’s what we were going for.

“Arif went for a much glossier sound which didn’t detract from the funk edge of things. It had a bit of real sparkle.”

AWB – better known as The White Album – was released in August, 1974.

The lead single, Pick Up The Pieces initially failed to crack the UK Top 40. But it was a different story across the Atlantic where the album steadily climbed the charts and knocked You’re No Good by Linda Ronstadt off the No. 1 spot. Pick Up The Pieces topped the Billboard Hot 100 on February 22, 1975. On the back of their Stateside success, the single later became a Top 10 hit at home.

“Watching the record take off was incredible. At one point the album and single were at No. 1 in the same week,” he said. “Until then we’d been fairly anonymous. But all of a sudden we were on the map. It was a case of, who are these guys? But we were welcomed with open arms and that was all down to the songs. People loved the music.”

Now, almost 50 years on, it remains a record Stuart is immensely proud of.

“It’s not an album I sit down and listen to, and never have done,” he admitted.

“I don’t know if any of us do that. You tend to check out the test pressing to make sure it’s okay, and then you don’t listen to it again. But I’m sure I can speak for everybody when I say we’re very proud of it. It was definitely the best work we could do at that time. They’re great songs and they still stand up. There are a few things I wish I’d done a bit better. But I could say that of every record I’ve ever been involved in.

“The White Album, song for song, stands the test of time pretty well. I think we really laid down a marker.”

THE Billy Sloan Show is on BBC Radio Scotland every Saturday at 10pm.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here