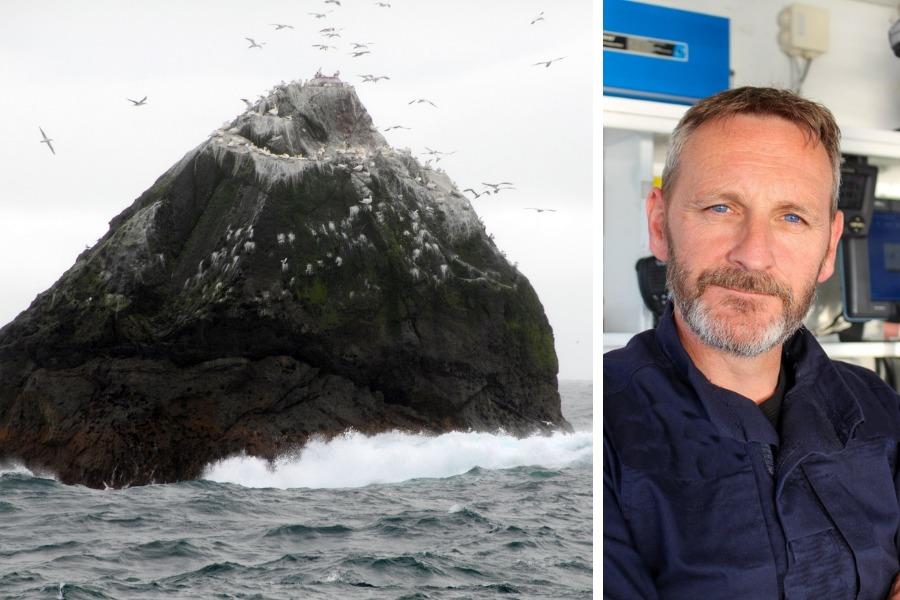

AARON Wheeler has chosen a fitting title for his forthcoming documentary on Rockall, that lonely, wind-scoured, uninhabited islet in the North Atlantic: “Rockall – the Edge of Existence”.

The edge of existence, indeed. When Aaron and an expedition team later this year set out for Rockall, which lies more than 200 nautical miles off the west coast of Scotland, it will mean a 16-hour boat journey each way. Other options – non-military helicopters, sea-planes – were impracticable so far as the expedition is concerned, because of the sheer distances involved, the high cost of fuel, and the absence of a safe landing-place from the air.

As Baroness Tweedsmuir, Minister of State at the Scottish Office, told the House of Lords as long ago as November 1971: “Very few attempts have been made to land on Rockall, partly because it is a very difficult operation from the sea because of the steep, smooth sides of the island's granite, and the constant swell, let alone frequent violent storms”.

No wonder that Cam Cameron, the Rockall 2022 expedition lead, acknowledges: “The greatest challenge is getting out there”.

Cameron, medic Dr Chris Grieco, and mountaineer James Price – who between them hope to raise £1 million for charity by living on Rockall for a week in June – will be filmed by Wheeler, director of photography Bryn Howard Williams and producer Ed Emsley. The current plan is for the film-makers to live on the boat while Cameron, Grieco and Price stay on the rock itself. Radio operator Adrian ‘Nobby’ Styles, the expedition’s fourth member, will join for at least the first 24 hours to make a ham radio broadcast.

For such a small, isolated, uncompromising place, Rockall has for decades excited considerable intrigue and attracted attention. A newspaper headline once described it as a “guano-stained speck that continues to exert an allure”.

It was formally annexed by Great Britain in 1955 – it has been described as the last territory to be taken into the British Empire – and it was incorporated into the district of Harris, Inverness-shire, by the Island of Rockall Act of 1972. It is now part of the Western Isles.

The island has from time to time featured in popular culture. The Guardian cartoonist Steve Bell once had Margaret Thatcher living on Rockall; more recently, he had Priti Patel saying that asylum-seekers would be processed on the remote islet. Rockall furthermore is familiar to millions of BBC radio listeners from its nightly inclusion in the shipping forecast, alongside such other areas as North Utsire, South Utsire, Shannon, Dogger and German Bight.

Periodically the island has been at the centre of diplomatic and legal wrangles, too; Ireland, Iceland and Denmark, on behalf of the Faroes, have at one time or another all claimed the rock.

In 2019, a dispute flared between the UK and the Republic of Ireland over Rockall and the surrounding 12-nautical-mile territorial sea. The Republic insisted that the waters were shared by all EU member states, but Scotland's Fisheries Minister, Fergus Ewing, warned that Irish vessels could be boarded for fishing within 12 miles of Rockall.

Dr Alasdair Allan, the SNP MSP for Na h-Eileanan an Iar, told Holyrood at the time: “In the context of the large increase in illegal fishing activity around Rockall, the Scottish Government has been absolutely correct to take the action it has in protecting the rights and interests of Scottish fishermen.

“Domestic law recognises Rockall as part of Scotland, and the Scottish Government clearly has a duty and an obligation to regulate fishing rights in the territorial waters around it, as is laid out in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea”.

The problem has continued to fester, however. A joint statement issued in January 2021 by the Republic’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, Simon Coveney, and the Minister for Agriculture, Food and the Marine, Charlie McConalogue, said they were engaging with Scottish and UK authorities to discuss Ireland’s “long-standing fishing tradition in the area”.

The Irish Times noted at the time that tensions had resurfaced over fishing access when the Donegal-based Northern Celt was “blocked by the Scottish marine authority and told they could not fish within 12 nautical miles of the uninhabited island”.

A Scottish Government spokesperson said this week: “The issue of fishing at Rockall is periodically discussed in meetings between the Scottish government and the Irish authorities as part of an ongoing dialogue about strengthening an already close relationship. Marine Scotland is responsible for the monitoring and enforcement of marine and fishing laws relating to Scotland's marine areas. It regularly monitors the seas around Rockall.”

The Scottish Government's position is that Rockall sits within the UK 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) as an uninhabited island within this zone; under the rules of the UN's Convention for Laws of The Sea Rockall generates its own territorial waters of up to 12 nautical miles). As a matter of law, there is no right of access for non-UK vessels to fish in these waters.

Rockall's claims to fame do not quite end there. Despite – or perhaps, because of – its forbidding nature, a tiny handful of hardy adventurers, including Tom McClean and Nick Hancock, has lived on Rockall for periods of between 40 and 45 days. (Hancock, as it happens, is the new expedition’s technical consultant).

In July 1985 McClean, a survival expert and a former SAS man and Paratrooper, came home to a pipe-band welcome on Mallaig after having spent 40 days on Rockall in order to re-affirm Britain’s oil and mineral rights. The Glasgow Herald reported: “With food for several months crowding him out of his 5ft by 4ft shelter, he spent the time watching distant fishing boats, seabirds, a bat, and a solitary seal, and maintained twice-daily contact by radio with his wife, Jill, at home at his adventure centre at Loch Nevis”.

McClean had in 1969 become the first person to row the Atlantic single-handedly, and crossed again in the smallest sailing craft, said of his experience of Rockall: “Crazy? It’s not crazy. It’s the way I make my living”. ITN footage of his time on the islet can be seen on YouTube.

In 1997 three Greenpeace activists occupied Rockall as part of its Atlantic Frontier protest against oil drilling plans in the area. They spent 42 days on the islet, living in a yellow, solar-powered pod, lashed to the rock with steel and heavy-duty straps.

They spoke of the territorial disputes that have long been stirred by Rockall. One of the activists was quoted as saying: "The seas around Rockall, potentially rich in oil, are fought over by four nations – Britain, Denmark, Iceland and Ireland. By seizing Rockall, Greenpeace claims these seas for the planet and all its peoples."

In 2014 Nick Hancock broke records by living alone for 45 days on Rockall, living in a home-made survival pod on a tiny ledge atop a 17-metre-high cliff-edge. He had originally planned to spend 60 days there, but his hopes were dashed by a fierce gale that resulted in much of his equipment and supplies being washed away in the ocean.

Hancock passed his time on Rockall in all sorts of imaginative ways. According to an article in Men’s Journal he “began talking to the homing pigeons and guillemots that landed on the rock. He read several books. He wrote blog posts. He watched shearwaters gliding centimetres above the waves. He observed two minke whales surface close to Rockall. He viewed fishing trawlers that passed by. He did housekeeping. He began taking Italian lessons. Oh, and he also raised $17,000 for the Help the Heroes charity”.

Now, in 2022, comes a new expedition. Aaron Wheeler, the film-maker, conceived of his Rockall project during lockdown, long before he learned of the planned expedition. “In the back of my mind somewhere I knew about this island”, the 24-year-old says. “In my head it was an island that people from the army would have to live on for the UK to say, ‘we owned it’. And then I looked into it and found out about people like Tom and Nick. We did initial filming with them both last August.

“I asked them how they dealt with loneliness and isolation and they said it hadn’t been an issue at all. Both of them are from military backgrounds. Emotionally, I think, their attitude was more about getting the job done. They were just too busy trying not to get washed off the rock by the waves, really.

“Now the documentary has morphed into a look into why we do such trips, why we risk our lives for arbitrary accolades and adventure,” Wheeler adds. “Going to dangerous places like [Rockall] reminds you how interested humans are in terms of exploring the Atlantic ocean”.

Why does he think Rockall has aroused so much fascination? “Nick said something to the effect that it was really difficult not to give Rockall a personality because it’s such an iconic thing, stuck in the middle of the ocean with nothing around it for 200 miles.

“It has really weird proportions, sticking out the way it does. Even the shape of it feels very iconic. I can imagine someone in prehistoric times almost seeing it as like a god or something, because it just seems so vivid and big and bold. Immediately, people are interested in Rockall because of that. But you also have lots of economics and geopolitics issues around – the value of the oil underneath”.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here