THE buzz surrounding the arrival of John Byrne’s new play is almost as vibrant as the album covers the Scots polymath designed for pop star Gerry Rafferty.

The Tron Theatre’s artistic director Andy Arnold admits: “I can’t remember in all my years in Scottish theatre where a new play has virtually sold out before the run even opens. It’s pretty extraordinary.”

Why all the excitement? Could it be because Byrne’s play, Underwood Lane, was scheduled to open at the Tron in Glasgow two years ago, but because Covid closed all theatre doors are we all the more anticipatory?

Or could it be because this isn’t any old play? It’s the work of John Byrne, the 82-year-old writing legend who created the likes of the Slab Boys trilogy and award-winning television such as Tutti Frutti.

Will Underwood Lane take us down the road to a collection of Byrne’s characteristic one-liners, caustic comments and the stylistic long sentences which make a Shakespearean soliloquy sound like a short grunt?

In short, can the writer of some 30 plays and screenplays still cut a rug when it comes to creating great theatre?

Then again, perhaps the frisson the theatre world is feeling right now has much to do with John Byrne’s relationship with Gerry Rafferty. The play was conceived to suggest the life and times of the music legend whose early life began in 13 Underwood Lane, the less than salubrious street near Paisley town centre.

Rafferty and Byrne were close friends. Both Paisley Buddies. Both men with a talent which took them to world prominence. Both products of their background – yet men who came to defy the lack of expectation their world placed upon them.

John Byrne was just along the road in the Ferguslie Park housing scheme, certainly not an area which bred success.

“It was once described as ‘the worst slum in Europe’,” says the writer/artist with a defiant grin, before adding a full-blown laugh. “I was very proud of that.”

So, he didn’t see a glass ceiling above his head? “No!” he says, emphatically. “I had no idea there was something there preventing me doing what I wanted to do. I got all the adulation and colour I could have ever wanted from Ferguslie Park, and I am eternally thankful for all of that.”

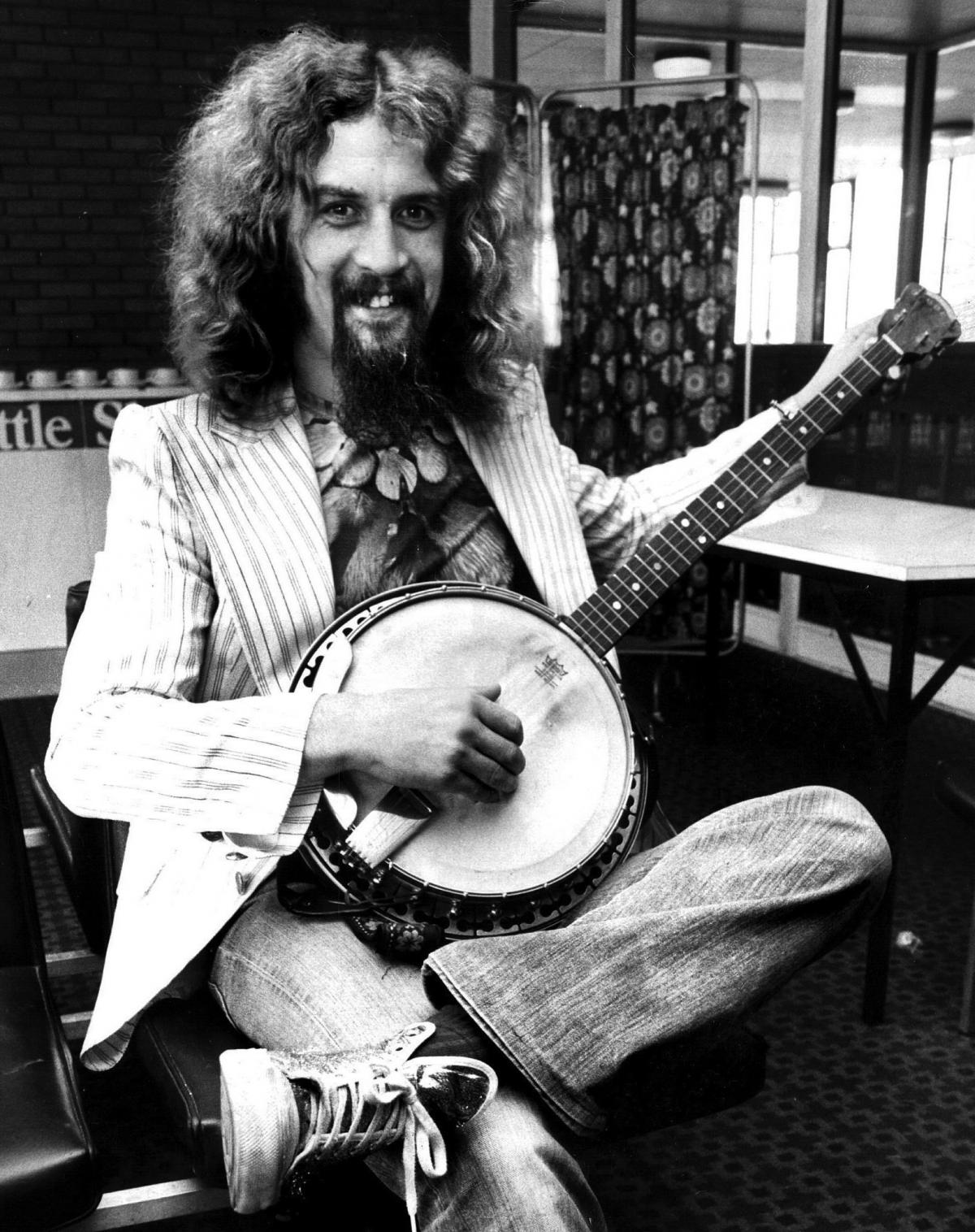

Rafferty, a former St Mirin’s Academy pupil, as was John Byrne, embodied too that sense of hope. Byrne recalls how the pair met. “I knew Gerry’s brother Jim when I worked at Stoddard's,” he says of the carpet factory near Paisley. “I had this three-string banjo that I’d bought for ten shillings, and I hid it behind a dust coat in the design room. One day, Jim came in and said: ‘Can I borrow that banjo; my wee brother is learning songs from Radio Luxembourg on a Sunday night’. Gerald would only have been around the age of ten.”

Byrne later remembers the youngest of the family singing with his brothers in three-part harmonies. It was soon clear to Byrne that Gerald, “was a born singer-songwriter. He was a genius.”

Gerry Rafferty, who died in 2011, aged just 63, once recalled his connection with John Byrne. “I got my first guitar when I was 12 and learned a few basic chords. John was a friend of my brother, Jim, and he would come round to my house. John had a couple of old guitars and a banjo, and he and Jim would play skiffle songs by the likes of Robin Hall and Jimmie MacGregor.”

Sixteen years ago, John Byrne knew he wanted to write a play that evoked Rafferty’s excitement with creating music. He also wanted to write about the battle over all kinds of adversities, which anyone growing up in Scotland in the late Fifties and early Sixties would appreciate.

There was no music scene as such. “The two main protagonists in the play are 19-year-old guys who live cheek by jowl in Underwood Lane, but hardly know each other, because one goes to a Protestant school and the other goes to a Catholic school. The story is about what happens when they form a band.”

Byrne adds: “I wrote a scene a night. It was the fastest I ever wrote anything. It’s very dark in parts, but also very funny.”

Initially, John Byrne hoped to feature the songs of the pop legend who wrote classics such as Baker Street, Whatever’s Written in Your Heart and Stuck in The Middle. And that certainly whetted the appetite of the theatre cognoscenti. “The original idea was to write the script for a musical based on Gerry Rafferty’s back catalogue. But I couldn’t get the rights to use his songs.”

He hoped. And he waited. And they didn’t materialise. As a result, Byrne couldn’t find anyone to develop and stage his labour of love. “I spent a lot of time trying to find a producer for it. I just couldn’t get anyone interested in it.”

Underwood Lane was consigned to a bottom drawer. However, in recent times Byrne had a flash of inspiration. “It was actually my wife, Jeanine, who asked me why I was trying to shoehorn songs from the 1970s into a play set in the 1950s and 1960s. It was like a bolt of lightning.”

The play was then pitched to the Tron Theatre’s Andy Arnold, who loved the script. And he agreed the play could be performed perfectly with songs of the period.

“There was the realisation that this was a play about the period in which Gerry Rafferty was growing up, rather than the fully-fledged version of Gerry’s life story,” says Arnold. “And once we knew for sure we couldn’t get the Gerry Rafferty songs, and since it is set in the early Sixties, we decided to use songs from that period such as Three Steps to Heaven, Teenage Love and It’s Only Make Believe.”

He adds: “The storyline looked at young people forming a band, and they would have been playing skiffle music at the time, and we knew we could recreate that sound brilliantly. That sort of musical realty works, while it would have been hard work to try and replicate something like Baker Street.”

The style of the play follows the familiar pattern of the former carpet factory designer. Byrne has once again created an ensemble piece featuring a set of interconnecting characters. To develop this ‘play with music’, Andy Arnold hired a team of actor-musicians, working under the aegis of musical director Hilary Brooks, whose previous theatre credits include Sunshine on Leith and Glasgow Girls.

But what of the dramatic narrative? “It comes from the rich characters John has created,” says the director. “There is lots of drama, but the narrative really comes from the development of the characters within. And we use the songs such as Teenager in Love to drive the storyline along.”

The play begins when Underwood Lane's Dessie (Marc McMillan) and Dark wood Crescent's Joey (Scott Fletcher) get a skiffle band together for an impromptu gig – uniting a group of young people whose paths might not have crossed ordinarily, and whose lives are irreversibly changed by the catalogue of events that unfold.

There is certainly conflict in the play. The pop career of Gerry Rafferty was deeply impacted upon by his relationship with music industry bosses. After meeting up with Billy Connolly, Rafferty joined The New Humblebees in 1969 and the perhaps unlikely combination – Connolly at the time was entrenched in banjo music and telling stories while Rafferty’s style evolved into a more popular sound – brought Scottish-level success.

However, Rafferty came to recognise their disparate talents. He went solo then had great success with Stealer’s Wheel featuring his old pal from St Mirin’s Academy, Joe Egan. Rafferty however always remained on the edges of the music industry, a cynical figure looking in. He was said to have written hits Stuck in The Middle and Star as a searing comment on the impact of the industry on a young performer.

John Byrne was entirely aware of Rafferty’s relationship with the music industry, his young friend’s entry into this shark-infested business. His character Dessie also falls foul of those who claimed offer to realise his dreams. “As the story progresses, Dessie is ‘shafted’ by a music producer, Eddie Steeples (Santino Smith),” says Arnold. “The contracts he signs are terrible. He has been completely out-manoeuvred and takes off to London.”

However teenage life is also very much about sex and romance and forming new relationships, isn’t it? It’s a complex time of heightened emotions and raging hormones, which fans of John Byrne’s work appreciate is a subject matter of which he writes wonderfully. “There are 10 of us on stage and the challenge is to fit all the pieces of the jigsaw together,” says Dani Heron, fresh from a sell-out stint of her acclaimed one-person musical play at Glasgow’s Oran Mor.

Heron plays ‘gobby mouthed’ hairdresser Maureen, who is mad jealous of Donna (Julia Smith) and the attention Dessie shows her. Heron explains; “Maureen is on the side-lines looking in on the band's development. Then when Dessie leaves for London we don’t know he has left Donna pregnant. When he returns, Dessie also has to contend with the fact the world he knew has changed.”

The local café has now been turned into a nightclub. By Eddie Steeples. And Donna has taken over as the lead singer of the band he left behind. Maureen certainly isn’t best pleased.

The Paisley-born actor loves her latest role, adding: “Maureen doesn’t join the band, but my character gets to sing quite a lot. There are moments when she sets the tone of the piece.”

Another reason why audiences may be so excited at the prospect of a trip down Underwood Lane is because the Catholic-Protestant divide that was so prevalent in the late Fifties and early Sixties offers real scope for both conflict and comedy. “There’s a Catholic priest, Father Duncan (George Drennan), in the story, who just happens to swear profusely all the time,” says Arnold, smiling.

Indeed, the social schism once prompted Gerry Rafferty to reflect; “Growing up in Paisley in the Fifties left me a little bit schizophrenic. So many of my reference points were not Scottish, they were Irish.”

Rafferty’s friend, music legend Barbara Dickson, pointed out that religion had a profound effect on the singer-songwriter. She says that Rafferty was a “deeply spiritual person, someone who was always seeking answers.” Raffety himself added, “I loved the ritual of the mass, and the music.”

Yet, the religious conflict underlined in Underwood Lane isn’t simply a memory of two generations ago. Dani Heron highlights the divide hasn’t entirely dissipated; the subject will still resonate with audience today. “When I was at school in Paisley, St Charles’ Primary, the Protestant school was just along the way, and there was this underlying feeling of difference.” She sighs. “It was mental to be honest.”

As well as the religious divide, the play underscores the generation gap. In the late Fifties, parents of that era simply did not connect with their offspring in a way they would today. The ‘teenager’ had only just been invented. Young people wanted to act and look different from their flat-capped fathers and hair-netted mothers. And they had new idols to worship such as Elvis, and writers who sang out for change, counterculture and new beginnings such as Keith Waterhouse and Stan Barstow.

It’s a period which Andy Arnold knows implicitly. He certainly brings a real musical education to the role of artistic director. “One of my first concerts I saw as a young teenager growing up in Southend was seeing Roy Orbison, Gerry and the Pacemakers and the Beatles,” he recalls, smiling. “And I do remember that the Teddy Boy era, of which this play fits into, which the older generation were frightened of.”

There are certainly lots of theatre fans who will wallow in the nostalgia that Underwood Lane recalls. Dani Heron highlights the power of the songs of the period to illuminate the popular mood. “The music speaks for itself. It’s really sexy,” she says in excited voice. “And it’s also really emotive. The lyrics are so bare you don’t ever have to think of what the songs are about.”

Yes, Underwood Lane isn’t a biographical play about the early life of Gerry Rafferty. “This is a tribute to Gerry,” says Andy Arnold. “He did grow up in that world. I really don’t know how much of Gerry’s real-life story is reflected in John’s storyline, but it is a story of a young musician growing up in that same street, so there will have been similar experiences.”

What we can trust from the play is that John Byrne not only lived through the period he knows how to colour in perfectly the outlines of the characters who grew up in that time frame, having done so successfully in his Slab Boys trilogy, capturing both the heady excitement and the cynicism of youth, all played out in a paint-spattered dungeon room in an Elderslie carpet factory.

He was also completely in tune with the mindset of the young musicians of the period, certainly following Rafferty’s career assiduously. The New Humblebums album sleeve, for example, was painted by Byrne. The record also contains a tribute to the artist in the form of the song Patrick. “I wasn’t surprised, but I was honoured to have a song written about me, we were so close,” says Byrne.

And if we don’t have explicit detail of the life of Gerry Rafferty played out on stage, does it matter? John Byrne knew so much of the man it will be a surprise if the essence of Scotland’s greatest-ever musical talent doesn’t manifest itself in spirit.

But the bottom line is that Underwood Lane is an immensely teasing theatrical prospect, a John Byrne new-old play that features young people finding their way in life via music, a rites of passage tale, about negotiating and surviving the world, which is Paisley.

“Yes, it’s all of that,” says Andy Arnold. “In all good theatre we get comedy and tragedy running alongside each other and that’s certainly what John Byrne offers up in this piece.”

Dani Heron agrees. “It’s almost like one of John Byrne’s paintings. It looks like a snapshot of a set of characters from this period. There’s always something in John’s writing that captures society as he sees it. And it’s fantastic.”

Underwood Lane, a Tron Theatre co-production with OneRen supported by Future Paisley, opens at Johnstone Town Hall on July 7-9 and the Tron Theatre, July 14-30.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here