IT was, no doubt, a brave time to be launching an International Festival of Music and Drama. A catastrophic war had ended only two years previously; now, in 1947, Britain’s myriad financial difficulties were reaching a crisis, with an austerity-stricken winter just round the corner.

Herbert Morrison, Lord President of the Council, had referred in a speech to national shortages of dollars, coal, manpower and food. One Glasgow political speaker had even warned that Britain was facing a second, domestic Dunkirk, of “blood, sweat and shortage”.

Despite (and perhaps because of) such doom and gloom, a great many people were looking forward to seeing what this new festival in Edinburgh could achieve.

It had been the inspired idea of Rudolf Bing, who had mentioned it to Henry Harvey Wood, who in turn had taken it up with the Lord Provost, Sir James Falconer. Bing was general manager of the Glyndebourne Opera; Wood headed the British Council in Scotland.

They all saw the festival as a means of bringing together audiences and artists from around the world. Sir James said he hoped that it would provide a spiritual tonic and physical invigoration after the strain of the war and during such an uneasy peace.

Scotland’s capital was the ideal choice for such an event, not least because Salzburg and Munich, the home of long-established arts festivals, had been bombed during the war. What the world’s leading artists needed now was a new home.

Months of planning, arguing and criticism had gone into the three-week-long festival, which had received funding of £60,000 from the Arts Council, private donors, and Edinburgh town council. The festivities opened on Sunday, August 24, with a special service at St Giles’. It was a stirring occasion. “The world will pass away, but music and love will last for ever”, declared the Very Rev Dr Charles L.Warr, Dean of the Thistle and Chapel Royal. “Today a new spirit is abroad. Scotland is awakening to the full significance of art and beauty”.

The atmosphere in Princes Street reminded some people of VE night. Baskets of flowers hung from tramway standards. Flags and buntings were everywhere. Beautifully laid-out garden plots had materialised at street-crossings in the city centre.

And already there were too many overseas visitors to count: they had arrived from China, France, the US, Switzerland, India.

Outside flag-bedecked Waverley station, Shakespearean players from London’s Old Vic, newly arrived by train, boarded an old, single-deck Coronation bus. For 30 minutes it refused to start. The actors disembarked and asked the kilted Festival manager, Hamish Maclellan: “How can we get a drink in Scotland on a Sunday? Is it necessary to have a passport?”

The Old Vic players were due at the Lyceum that night (Trevor Howard was one of the stars of The Taming of the Shrew). Elsewhere, there were Sadler’s Wells Ballet Company, and the Unity Theatre Company, and art exhibitions, and, at a packed Usher Hall, L’Orchestre des Concerts Colonne of Paris, with a programme of Haydn, Schumann and Cesar Franck.

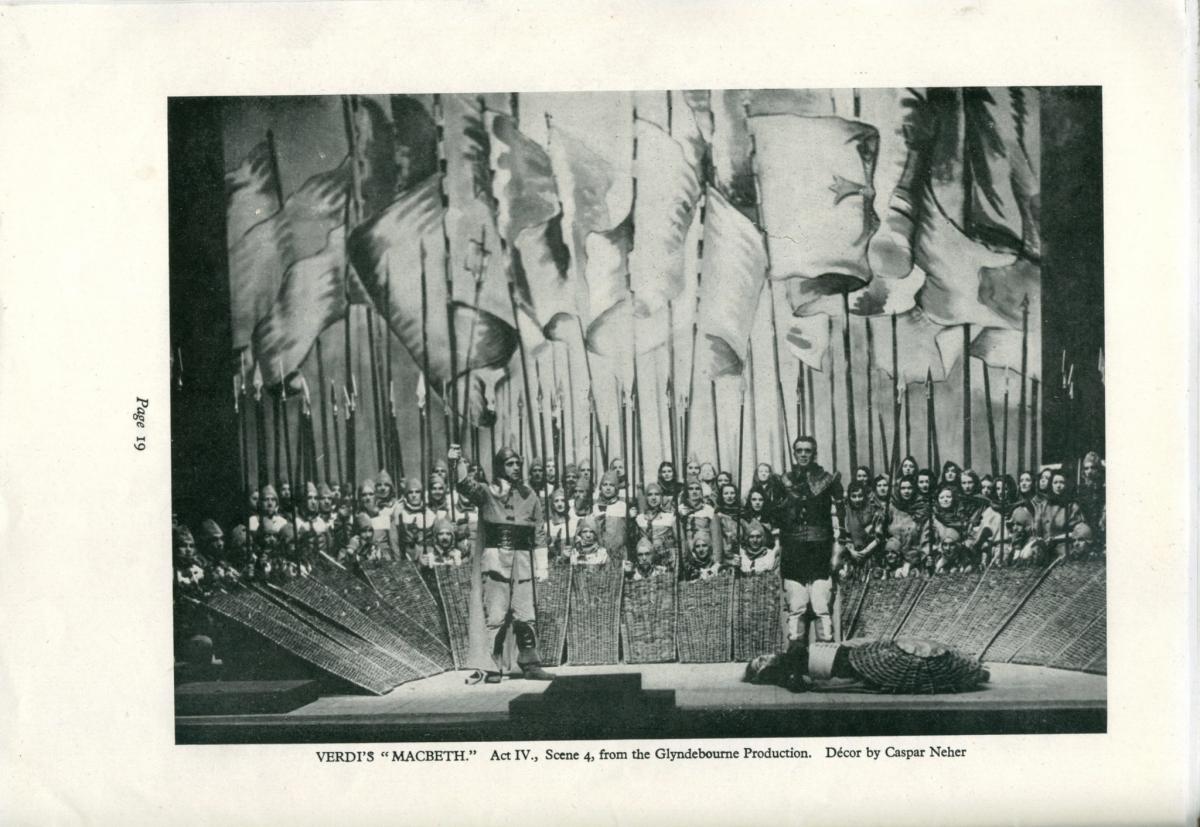

In the days that followed, Margot Fonteyn starred in a Sadler’s Wells production of Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty, at the Empire Theatre. The Glyndebourne Opera Company presented Verdi’s Macbeth and The Marriage of Figaro at the King’s.

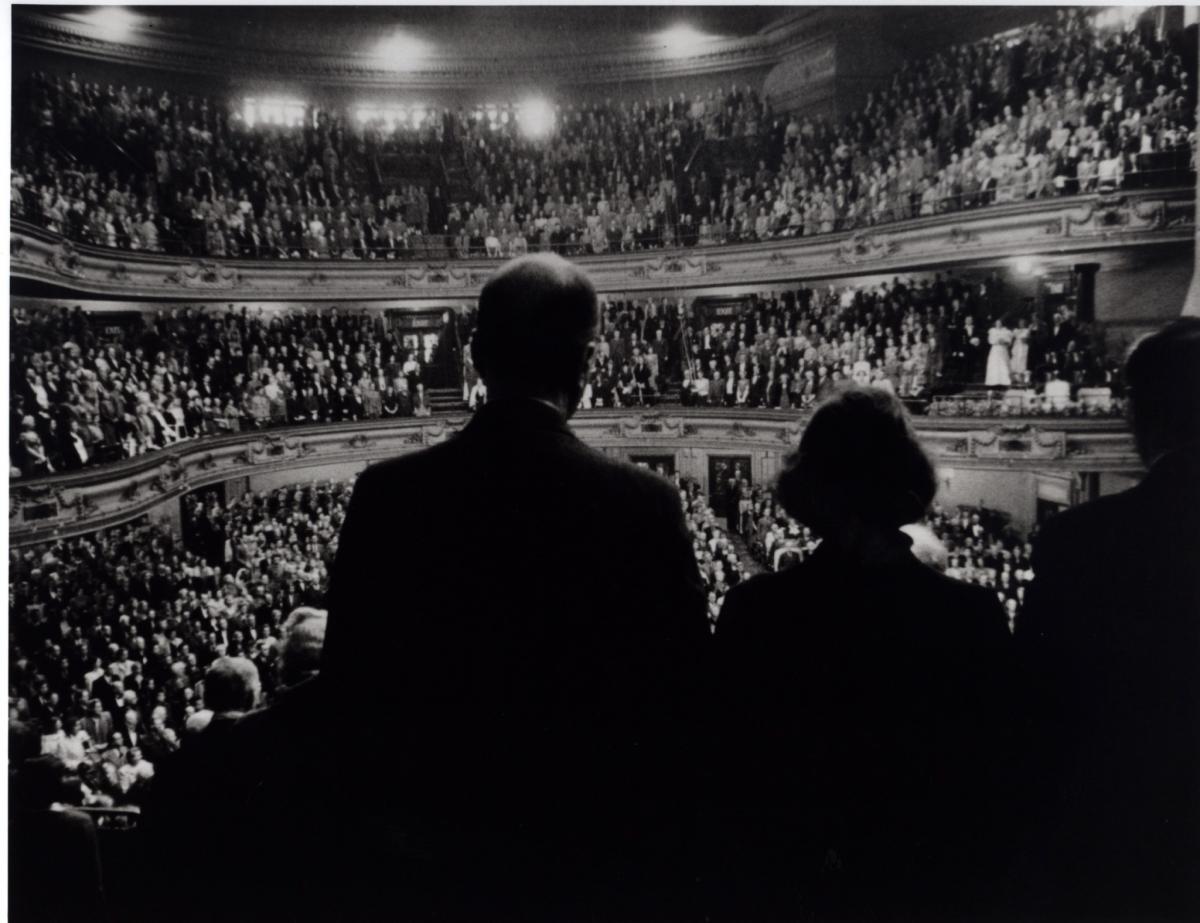

Demand for tickets was heavy. People living outwith Edinburgh could now only get seats by postal application, or by getting their Edinburgh friends to book on their behalf. Tickets were at a premium, especially, for the concerts at the Usher Hall – the Halle Orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic under Bruno Walter, the Orpheus Choir, the Liverpool Philharmonic under Sir Malcolm Sargent, the Scottish Orchestra, the BBC Scottish Orchestra. String quartets and trios played the Freemasons’ Hall.

Lengthy queues for seats at the Festival Club in the George Street Assembly Rooms were a daily occurrence. Mr Bing, the Festival director, said he was surprised by the extent to which people had wholeheartedly flung themselves into the occasion.

In some subtle way, remarked The Glasgow Herald, the event had touched the spirit of the entire community. Several city householders who had been unable, at the last minute, to keep their promises to put up Festival visitors had contributed sums of ‘conscience money – £19, in one case – to the Festival authorities as tokens of regret.

French visitors piled into an exhibition at the Murrayfield Indoor Sports Club, staged by the Society of Independent Scottish Artists. The British film actors Kathleen Byron, David Farrar and Derek Bond all came to town. (In later life Byron would have a cameo role in Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan).

The famous Italian baritone, Italo Tajo, went to Leith’s Alhambra Picture House to see The Barber of Seville, which had been made from stage performances in Milan. Alec Guinness played Richard II in Sir Ralph Richardson’s superb production.

Attlee’s Minister of Fuel and Power, Manny Shinwell, relaxed his ban on floodlighting and allowed the Castle to be floodlit on four nights – he had initially declined, unwilling to create a precedent at a time of a fuel shortage. The floodlighting stopped Princes Street promenaders in their tracks.

Many distinguished visitors, dazzled by what they had seen of the city, urged Edinburgh to make the festival an annual event, among them The Observer’s editor and drama critic, Ivor Brown, who said: “I feel Edinburgh is one of the greatest stages in history”. Indeed, by the end of the first week, plans were being laid for a Festival in 1948. On September 5 Sir John Falconer confirmed that it would become an annual event.

On Saturday, September 6 the writer Eric Linklater, at a Scottish P.E.N. lunch, declared that in the festival he had found the sort of air that should have clothed Britain after its historic victory over Hitler. Here, it seemed, despite our alleged poverty, was a realisation of victory, he added.

The following day saw the Queen and Princess Margaret attend a Glasgow Orpheus Choir concert at the Usher Hall. A black-out interrupted their enjoyment of Verdi’s Macbeth on the Monday evening.

Bruno Walter and the Vienna Philharmonic received a five-minute-long ovation at the Usher Hall on the Tuesday night.

Thousands of people had been unable to get tickets for the orchestra’s series of five concerts, so an extra event was laid on for Saturday, September 13. Music-lovers began queuing at 6am on the Friday for tickets.

Orchestra members, who were staying at a hostel, organised a football match between their strings and brasses. To the winner went the largest cabbage in the hostel kitchen.

The Festival ended that Saturday night with members of the Festival Club singing Auld Lang Syne in the ballroom at midnight.

The Festival had even managed to give rise to a new event: eight uninvited theatre groups had turned up at the Festival, thus creating the Festival Fringe.

The first Festival, then, was an outstanding success, achieving all that its organisers had dreamt of. Sir John Falconer said the aim had been to create a “haven of culture organised and maintained on the highest level”, one that would offer people refreshment, satisfaction, and spiritual and intellectual content.

“If that could be done”, he added, “it would assist to mould the progress of civilisation on higher lines”.

Seventy-five years later, the Festival has made considerable progress towards that aim.

https://www.eif.co.uk/

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here