THE year 1971 saw the release of many landmark albums in the field of rock music. So many, in fact, that the music journalist David Hepworth once wrote a book that catalogued the most influential of them.

Acts such as David Bowie, Led Zeppelin, Carole King, the Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, Marvin Gaye and Joni Mitchell all released LPs during 1971. Indeed, as Hepworth recounts in 1971: Never A Dull Moment, those 12 months saw the launch of a huge proportion of the most memorable albums ever made.

There might not have been the same degree of innovation in the official singles charts, but for five weeks that summer a Scottish outfit, Middle of the Road, occupied the number one slot with an indecently catchy novelty tune, Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep.

The quartet became only the second Scottish act to reach the top spot. The first had been Marmalade, in 1969, with a cover of the Beatles song Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da. It was the best-selling single in the UK for three weeks in a row (“outrageously commercial” with an “infectious, good-time party atmosphere”, Brian Hogg says of it in his book, All That Ever Mattered: The History of Scottish Rock and Pop).

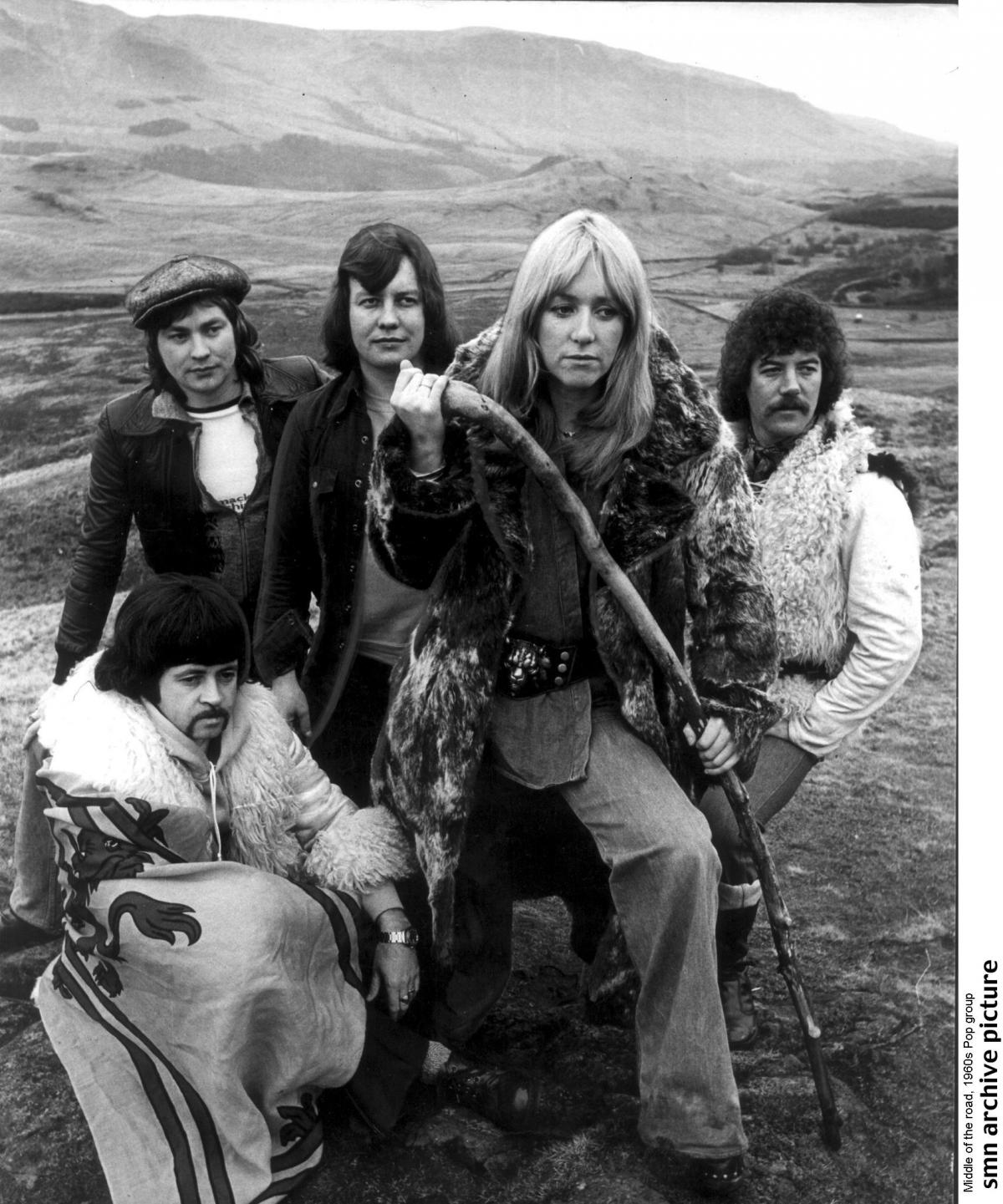

Middle of the Road – Sally Carr, Ken Andrew, Ian McCredie and Eric McCredie (Neil Henderson later became their fifth member) – had originally worked under the name of Part Four, then Los Caracas, and, after constant touring and invaluable exposure on the TV talent show, Opportunity Knocks, settled on their new name. Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep, penned by one Lally Scott, was a dubious proposition for Andrew and the McCredie brothers, but Carr persuaded them that it was sufficiently catchy to record. The three men had to be “plied with a considerable volume of alcohol before being persuaded to perform it”, in Andrew’s later words.

The song was a substantial hit in the UK and other countries. It and its successful follow-up, Tweedle Dee Tweedle Dum, which reached number two, were both “nonsense songs”, as the band’s own website acknowledges, but the group went on to have other hits, including Soley Soley and Sacramento.

Interestingly, Ken Andrew, interviewed by Martin Kielty for his book, Big Noise, speaks of the “extremely severe criticism we suffered from the British press”. Generally, it passed them by, as they were so busy working abroad. The culprit was Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep: “It’s been loved, hated, ridiculed, praised, but mostly blamed for bringing European pop music into disrepute. As if it needed it, by the way!”

The Official Singles Charts have just turned 70. In all, 46 songs by Scottish artists have hit number one on the chart since 1952, starting with Marmalade, Middle of the Road and, in 1972, a stirring rendition of Amazing Grace by the Pipes & Drums and Military Band of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards.

Pride of place on the list is claimed by the DJ Calvin Harris, who has had 10 number ones, either on his own or in collaboration with other artists. More recently, Lewis Capaldi has topped the charts with three different songs. His single, Someone You Loved, has officially become the UK’s most-streamed song of all time.

Other Scots who have claimed the coveted spot include Pilot (three weeks at the top with their hit January, in 1975), the Bay City Rollers (Bye Bye Baby, and Give a Little Love, that same year), Slik (Forever and Ever, 1976), Lena Martell (One Day at a Time, 1979), Aneka (Japanese Boy, 1981) and Kelly Marie (Feels Like I’m in Love, 1980).

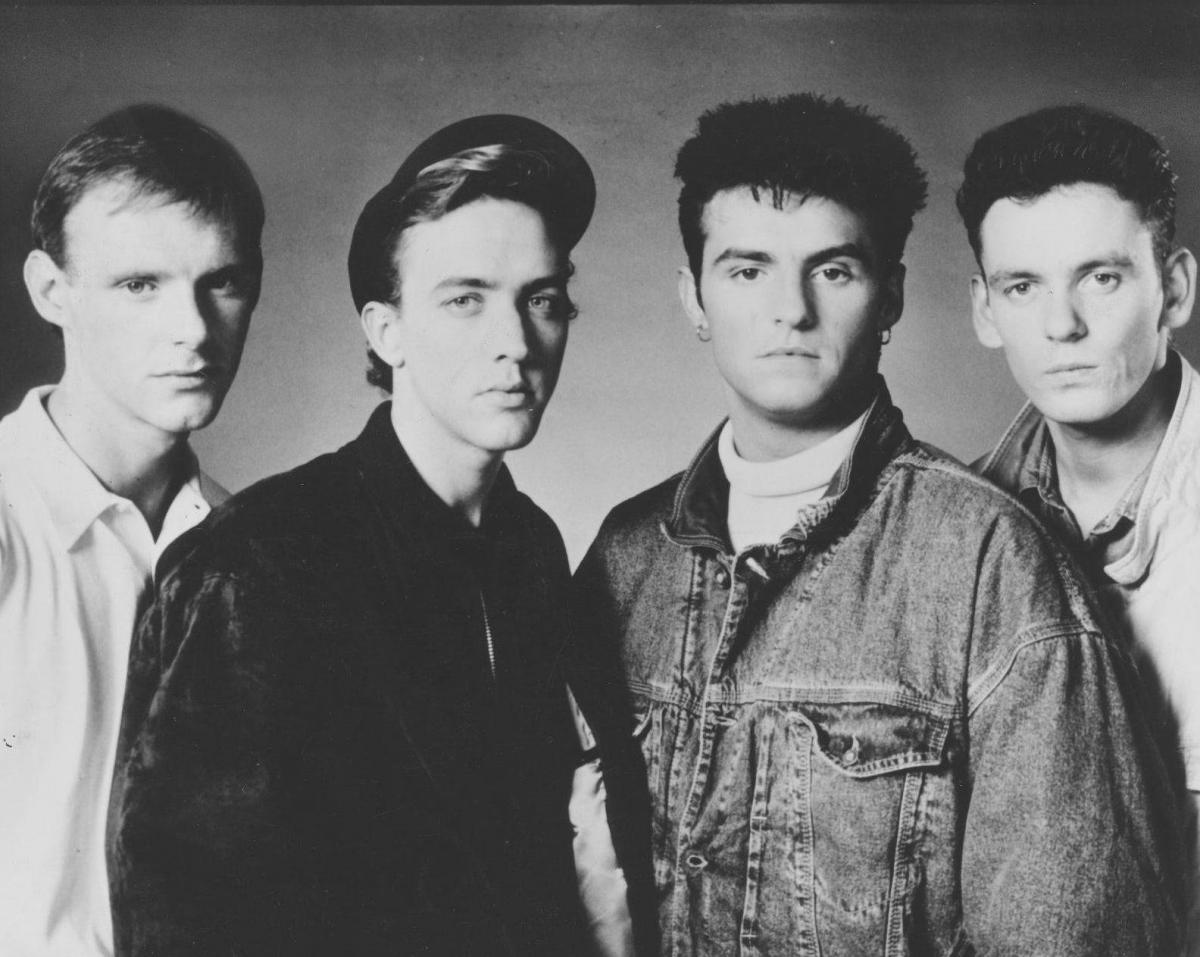

Wet Wet Wet have had no fewer than three chart-topping songs: With a Little Help from My Friends (1988, with Billy Bragg), Goodnight Girl (1992) and, most famously, Love is All Around (1994), from the Four Weddings and a Funeral film soundtrack. It was at number one for 15 weeks, the joint third-longest reign ever.

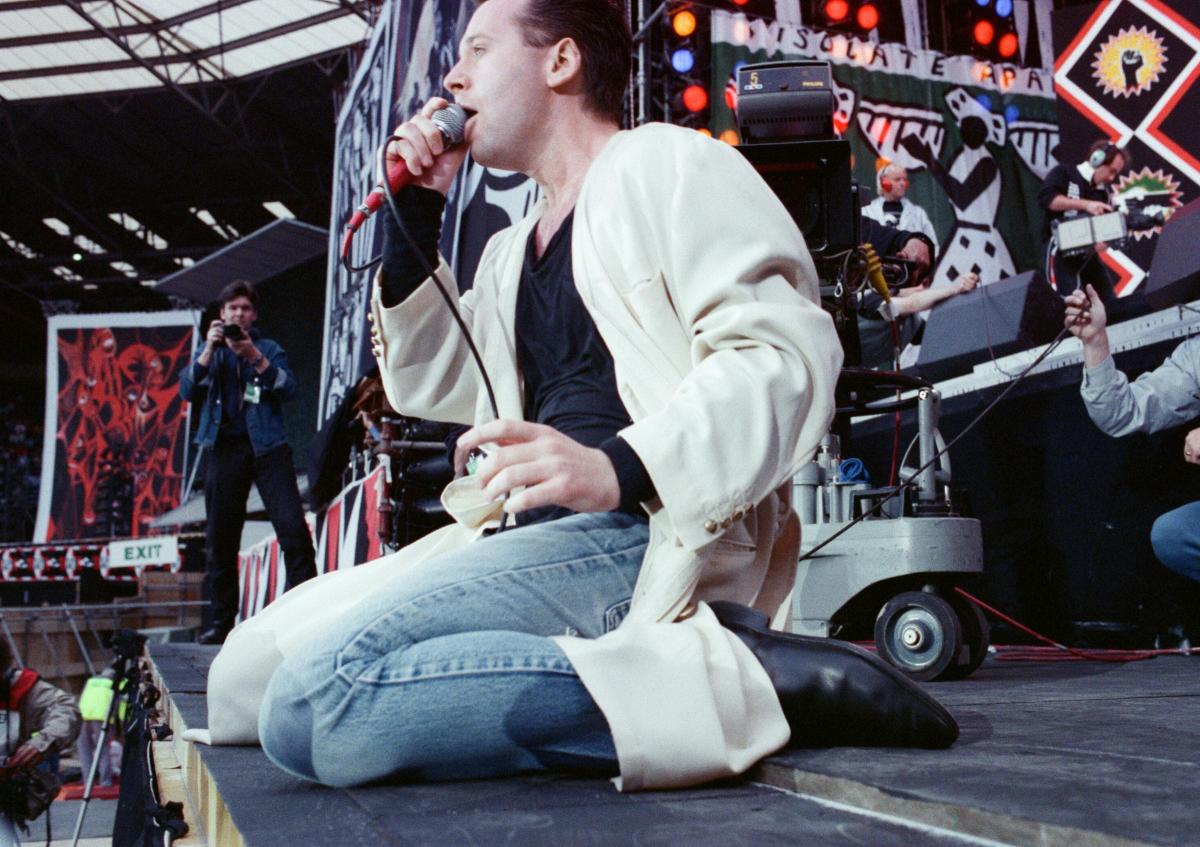

Other chart-topping Scots include Billy Connolly (D.I.V.O.R.C.E., 1975), Simple Minds (Belfast Child, 1989), Lulu (Relight My Fire, with Take That, 1993), The Bluebells (Young at Heart, 1993), Stiltskin (Inside, 1994) and Darius (Colourblind, 2002).

Barbara Dickson and Elaine Page hit number one with I Know Him So Well, in 1985; the previous year, Jim Diamond’s I Should Have Known Better was for a time the most popular single in the UK. Sandi Thom (I Wish I Was a Punk Rocker (With Flowers in My Hair, 2006), David Sneddon’s Stop Living the Lie (2003), Michelle McManus’s All This Time (2004) and the Proclaimers’ (I’m Gonna Be) 500 Miles (2007) all make the select list.

Lulu’s case is especially interesting: after all, she had her very first chart hit back in 1964, with Shout, and had a string of other 45s – Leave a Little Love (1965), The Boat That I Row (1967), Let’s Pretend (1967), Love Loves to Love Love (1967), Boom Bang-a-Bang (1969) and David Bowie’s Man Who Sold the World (1974), none of which got beyond number two.

When she finally reached the pinnacle with Take That, Lulu broke the record between an act’s chart debut and their making it to number one: in this instance, 29 years and 148 days after her debut with Shout. Recording Relight My Fire was, in the verdict of the Sunday Herald in 1999, a nicely judged touch of kitsch that introduced her to a new generation of pop fans.

Looking back at the list of successful Scottish acts since 1969, it’s hard to overlook the fact that pop and rock has become more sophisticated, more diverse, more fractured. From bubblegum pop and glam rock we have seen, to mention just a few later trends, power pop, punk and new wave, jazz rock, hip-hop, indie rock, electronic dance music (EDM), techno, grime and ambient.

The ways in which fans consume music have also changed beyond all recognition since the early 1970s. Back then, they bought vinyl – LPs and singles – and cassettes and eight-track cartridges.

Radio DJs (John Peel was a lastingly influential figure when it came to promoting new bands) and TV shows such as Top of the Pops and the Old Grey Whistle Test had substantial audiences. Back in the 1970s, schoolkids would sprint home at lunchtime on Tuesdays to hear the latest chart rundown on Radio One (others, more enterprising, would smuggle transistor radios into school).

Today, we can download songs onto a laptop or smartphone in mere seconds. Streaming services such as Spotify, which alone has nearly 200 million paying subscribers, are dizzyingly popular. Vinyl, like CDS, faded in popularity, but both remain popular.

The changed climate is reflected in a recent article by the Guardian’s Alexis Petridis. The UK Singles Chart, he observed, seems to have entirely lost its grip on the public imagination. “It no longer feels omnipresent,” he wrote. “When was the last time you walked into a bricks-and-mortar record store and saw the Top 40, or read a news piece about a hotly contested ‘battle’ for No 1? When was the last time you overheard music-mad teenagers talking about where a song was in the charts? Even the Christmas No 1, once the most prestigious placing of all, barely musters any attention.”

At 70, Petridis concludes, the singles chart finds itself largely unloved, ignored and dismissed as irrelevant: “To paraphrase the gloomy First World War song, it seems to still be here because it’s always been here. Without wishing to spoil the birthday celebrations, it’s hard not to wonder if it will be around to celebrate its 80th.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here