LITTLE Ollie Mellon was saved with a high-tech artificial lung – after his own were crushed when he was born with all of his abdominal organs in his chest.

Without the state-of-the art technology, he would not have lived to reach two days old.

His mother Lauren McGill, 27, now believes his first kick from inside the womb was her son telling her he was worth fighting for.

Just one day after feeling her unborn baby move, the young mother was told at her routine 20-week scan that Ollie’s stomach and intestines were squashing his tiny heart and lungs.

One doctor told her it would have been “easier to tell you if there was no heartbeat – then you wouldn’t have to make a decision”.

But despite every one of his abdominal organs, including his liver, spleen and kidneys, being in the wrong place at birth, Miss McGill knows she was right not to give up on her baby – now a happy, healthy one-year-old.

Her message to other families facing the same plight now is to “have hope and faith – these babies are just incredible and fight against all odds. Ollie is proof of that. He surprised everyone.”

The child had congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH), a rare anomaly that affects an average of just three babies in Scotland each year.

Ollie Mellon from Alloa with mum Lauren McGill

It meant his abdominal wall muscle, which separates the abdomen from the chest cavity, failed to develop properly in the womb. This allowed the other organs to push up, leaving no space for his heart and lungs to grow.

Ollie was so ill it took 20 doctors and nurses to deliver him safely at Glasgow’s Queen Elizabeth University Hospital on September 18, 2020.

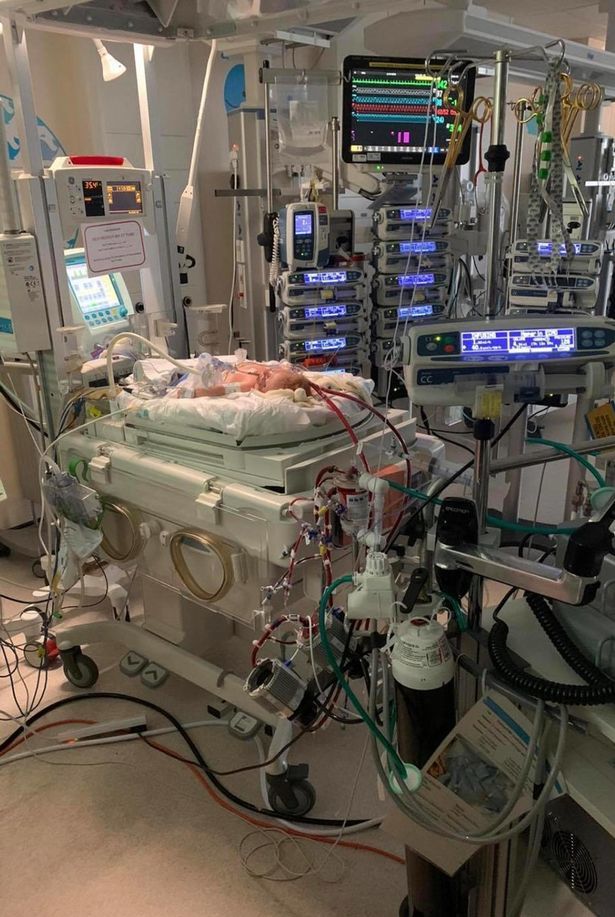

They did not even have time to weigh him before he was hooked up to full-life support, as his initial breath could have crushed his lungs further.

But his oxygen levels continued to plummet and, less than 24 hours later, doctors used a high-tech artificial lung in a last-ditch attempt to keep him alive.

Devastated Miss McGill and partner Cory Mellon, 28, from Alloa, Clackmannanshire, were warned that the procedure carried a high risk of brain bleed and stroke.

She says: “We had no choice, because they said if they didn’t put him on it he wasn’t going to make it through the night.

“I was just numb. They told us he was very unstable and they had tried everything – he was maxed out on all his medication.

“I remember going back up to our room and we just sobbed and sobbed.

“In the beginning, when I got my scan, they thought it was only his bowel and stomach that had moved up. It was only after he was out we found out that every organ was in his chest.”

Ollie Mellon from Alloa

The artificial lung machine, known as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) accessed his blood through a vein in his neck and circulated it outside his body, removing carbon dioxide and adding oxygen, as his lungs would do. The oxygenated blood was then warmed back up to body temperature and pumped back into his body through a second vein in his neck.

Miss McGill, an early years educator, said: “They were telling us how bad it was but I didn’t want to accept it.

“It wasn’t until I saw him on it that I just broke down, seeing all these things that he needed to keep him alive. He was just so tiny and the ECMO machine was huge.”

Ollie was expected to need the specialised treatment, which is only available to babies in Scotland at Glasgow’s Royal Hospital for Children, for weeks to give his lungs time to develop. But remarkably he came off it after just four days.

Still on a ventilator, he then faced a risky seven-hour operation at 10 days old, when surgeons put the out-of-place organs back into their correct positions in the abdomen.

The large gap in his abdominal wall muscle was then sealed with a synthetic patch using a material similar to what raincoats are made from.

But as his abdomen was so thin after containing no organs, to allow his skin to stretch and the internal swelling from the surgery to go down, doctors had to leave the wound open for four days before closing him up.

It was only while he was recovering from surgery that Miss McGill and her partner, an electrician, finally got to hold their baby for the first time.

Ollie’s lungs are still much smaller than a typical 12-month-old – one is only half the size and the other just a quarter of what it should be.

But Miss McGill said: “Nothing holds him back. He is on the move and is not far off walking – and he loves to be the centre of attention. He’s so loving and just wants to make everyone happy. He is a very determined little boy – he has been since day one.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel