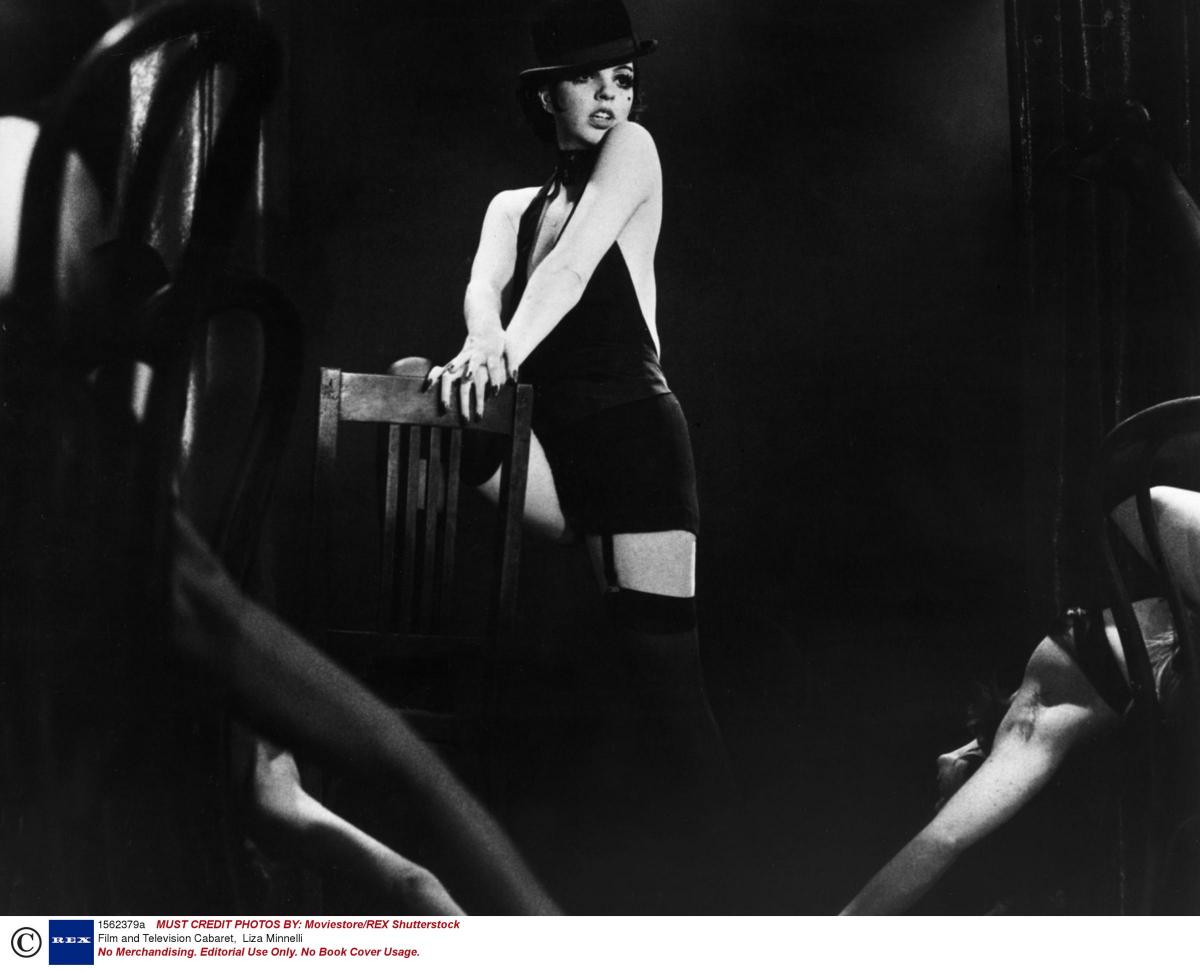

Human beings have always worshipped icons, be they religious or cultural, and gay people have always had theirs. So what makes a gay icon? The most famous and enduring of them all is, of course, Judy Garland. Most of her audience members were gay men, and it was the same for her daughter, Liza Minnelli. Musically, I have always adored them both, and sadly, like many performers there are some similarities between us, in that, even at times of extreme misery, addiction, self-loathing and deep-rooted insecurity, we managed to pull performances out of the bag (mine obviously on a tiny scale in comparison), so that no-one could have possibly known what was really going on behind the scenes.

I adore Judy Garland's voice. I was brought up with her music and, along with Sammy Davis Jr, they influenced my childhood desire to perform. Punk completely passed me by, as I was lost in American showbiz-land by the age of 10. Both Garland and Davis were born hugely talented; both suffered enormous personal anguish and terrible treatment by the institutions that made them.

This strength-through-adversity vibe seems to be the main ingredient of those who achieve gay icon status. Whether it be Judy or Dusty Springfield or Cher or Elvis (the latter being more a lesbian thing), all have or had an inner strength which ensures that no matter what personal insanity prevails, and whatever it takes – thy make-up shall be applied and the show must go on – even if it results in early death.

Unfortunately for some who burn so brightly and intensely, it can only be for a brief while. This need to push against repressive forces and our own internal saboteurs, to blossom and shine as an authentic force, is projected onto the big feminine performer heavyweights worshipped by the gay male community in particular. And clearly it represents, on a smaller scale, our need to be what we are. The old gay lament, I Am What I Am, is undoubtedly our anthem. While it’s true that many people in the UK are more supported by their communities than they were when I was young, many people still endure persecution and abuse simply for being themselves. Legislation can change law, but not always mindset.

As a person born with performer gifts, I have been drawn to many of the great gay icons listed above, yet with female performers like Judy or Dusty, I don’t see that as a projection of my lesbian desires, though perhaps the male performers I have adored are indeed an embodiment of a part of me that identifies as masculine. After all, we all contain elements of both genders.

Stars like Judy or Elvis have a wide appeal simply because the magnitude of their performing selves hypnotised and seduced millions of people from all walks of life. When I watch Shirley Bassey singing This Is My Life, I cry my eyes out because of my own life struggles, which have almost killed me at times. I hang onto every word and every belted-out note and I feel a deep connection with the passion and the strength and the recognition of all life’s difficult emotions. I understand not everyone else feels these emotions so intensely, but, due to a number of factors, I do.

As documented in my book, 1979, I was the first lesbian on the planet – or at least, on my planet, growing up in Scotland during the 1970s, when there seemed to be no-one else like me. I had my suspicions about various tennis stars on TV (and as it transpired I was right), as well as a crush on Noele Gordon as Meg Mortimer: the matriarch of TV soap Crossroads, which was synonymous with family teatimes throughout my childhood.

There was also an auntie of mine. She was married, like almost all women of that time, but unhappily, to an equally unhappy, downtrodden man. Like many, they had hooked up for a bizarre set of reasons involving family politics and personal fears. She favoured the trouser and wore very little make-up: a rarity in working-class culture of the time. She was outspoken and acerbic, fought injustice on a small community level, was moody and sarcastic, took no shit.

She liked a special-occasion cigarette, which first shocked me in the summer of 1976 when, on a family visit to London, she lit up. The obligatory tourist haunts were attended, but neither the Crown Jewels, the changing of the guard nor even the room with planets on the ceiling illuminated my 10-year-old self. For me, all those things, and a world-famous heat wave, were eclipsed by the sight of a real-life American cowboy, who occupied the hotel room next door to us and would slink down the corridor in his Levis and boots, tilting his Stetson to passers-by. It was a moment of epiphany as he seemed to awaken the man in me, the man I needed to be, in order to make women want me as things felt so black and white back then, no grey areas permitted.

I wanted him: not in a way I might have done had I been a young developing gay boy, but in another way, the same way I felt when I saw images of Elvis, a persona I wanted to embody myself, with a desire to base my own image on this god I saw before me. I think I must have been the only person in London that summer grateful for the sweltering heat as it drew me nearer to the cowboy as I pretended to need ice from the machine by the lift every time he did.

The holiday was often marred by my trademark tantrums as my mother forced me into the dresses, sandals and necklaces I felt stifled my true self and could potentially lead to public mocking by passers-by. A mum just wants to see her little girl being a little girl, but, feeling miserable in those mother-friendly outfits, I relied on the burgeoning, performer side of my character to pretend that I was playing the part of a girl incarcerated in the prison of family. What beautiful, sophisticated woman would want me in a nylon, pink, flower-patterned dress with a sewn-in belt and a pair of Dr Scholl’s?

The holiday continued, it grew hotter and my auntie smoked and drank more until it could no longer be described as occasional and my tantrums surpassed Liz Taylor’s in Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, until finally my mother, beaten down by heat exhaustion and sightseeing, agreed while shopping in Carnaby Street to buy me a pair of high-waisted, checkered trousers, a high-collared shirt that buttoned at the back, and a thick, tan belt with the American flag as the centrepiece fastener. I was finally soothed and ready to return to Scotland, reborn in the USA via London. Upbeat and hopeful, I boarded the beautiful British Rail sleeper train, in my head, part private detective, part cowboy embarking on the journey and mystery of my being.

In my years as a young and upcoming comic in the 1990s, I presented the first entertainment show for gay people on British television, and had the honour of interviewing legends such as Liza Minnelli, Sandra Bernard, k.d. lang, Martina Navratilova, Marc Almond and the adorably eccentric Quentin Crisp, all of whom have achieved a level of gay iconic status in some measure.

I guess we should separate those who have contributed to the gay cause but who do not get much iconic recognition because they are not aligned with glamour or overt sexuality, those who have fought for the civil rights we have today, and those who have dared to be different, whether it is the old drag queens and trannies who put on their gear and walked down their streets with a clear "f*** you, this is me" message – all of us and any of us who dared to be ourselves in a unforgiving era. It’s easy to adore the exuberance and voices of Bassey, Streisand and Garland and all the great, gutsy, glamorous performers, but what of those who may not be as glittering? What of those who made their mark without a stage, but through the page or on the soapbox? I’m thinking of Harvey Milk, the first openly gay politician elected to public office in 1970s California; he became instrumental in the gay civil rights movement and was later gunned down and killed by Dan White, a heterosexual Christian city supervisor.

Or James Baldwin, the poet, writer and activist born in 1920s Harlem, who spoke so insightfully about life.

In terms of now, Jeanette Winterson is probably the lesbian and artist I admire the most. Like me, she is northern and adopted, and in my mind it’s hard to beat a life story that begins with being locked in a coal cupboard, and includes birthing a book by your mid-20s that will become a groundbreaking TV series (Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit).

Sadly, I did not go to university, nor do I have any degree to mention. My torturous young years were spent regrettably in an alcoholic haze as a provincial lesbian who was dancing around to Hazel Dean in the gay clubs until my fate was sealed as a comedian in London in 1991. Most of my early years in clubs as the only openly gay woman who just wanted to talk about my crazy life but had to deal with the numerous and persistent heckles of “f***ing lesbian” – something that I hope today's young people might have been spared.

It takes all of us in all our guises to make the changes. We are all needed, as are our allies in business, in the arts, in everyday walks of life. And for those of us who have contributed to being out there before many others of our kind, we must also look up to those who came before us. Whether you have spent your life tirelessly campaigning like Peter Tatchell or those lobbying through establishments like Stonewall, or whether you are gay presenting a light and mainstream television programme without anything meaningful being said, it all matters, because it means that LGBT people can grow in their acceptance and get on with their fully authentic lives doing what they want, adding to a rich and colourful, diverse mix of communities and careers. Young LGBT people need role models: brave and open people they can look up to. This is important in industries like sport, particularly women’s sport, and in the music business.

Surely a sensible and compassionate move would be to fund schools properly in order to educate kids about homophobia and invite people in with their own human stories. There is still work to be done as murderous homophobia persists close to home and further afield, where it is amplified in various African states and in Russia. Let's not forget that despite its progressive legislation, South Africa has an epidemic of corrective rape against lesbians, one of which led to the brutal murder and gang rape of Eudy Simelane, the openly gay activist and football captain of its national female team.

I hope the Icon Awards evening is a success. I hope that beyond a party (gays love a party!) it will be also be a time to recognise the big, beautiful, mixed bag of men and women who are LGBT: some worshipping traditional roles within a complex subculture, most of us inhabiting part-masculine, part-feminine territory in our images, in our desires, in our skills and tendencies.

With 50 approaching, I am looking back now and feeling wistful about all of the old gang – the crazy lesbians I have loved and known, the gay men I lodged with, drank with and even, on one occasion, slept with. Not all of them have survived the passage of time; many were too wounded to make it. Some drowned in addiction, having attempted to obliterate the pain of childhoods spent in a less accepting era. Some of the women were ravaged by cancer, some of the men by Aids before the improvement of medicine.

But my mind has taken me back to the Black Cap in Camden, London – surely one of the most iconic gay pubs in the UK back then, where on a Sunday afternoon in the late 1980s, all of us, men and women, would cram together to watch legends like an early Lily Savage and Regina Fong perform the best drag shows I had ever seen.

Incidentally, if Oscar Wilde – probably the most famous and most quoted gay man of all time, were alive and writing today, he would probably be slagged off by some faceless egg on Twitter, calling him a whinging poof.

Here’s to us all.

The inaugural Icon Awards, celebrating Scotland's thriving LGBTI community, will take place in October. To vote for nominees in awards such as Politician of the Year and Employer of the Year, visit www.icon-awards.co.uk

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel