I WAS that kid who drew all the time. There’s one in every school, almost every classroom. At some point, around the age of eight, I started saying I wanted to be a cartoonist. Unlike my ever-patient and indulgent parents, my teachers were not enthusiastic. I remember being told time and again that there was no worthwhile career in it. After some 20 years of work as a cartoonist, much of that spent in the company of a doubly patient and indulgent wife, it’s safe the say their arguments failed to dissuade me.

But no-one ever said it was dangerous.

Nothing makes you more acutely aware of threat than a big man with a gun assigned for your protection. Attending a conference last September, transported in vehicles checked by bomb-dogs, with uniformed and plainclothes police by the door and snipers on an adjoining roof, this point was driven home. I’ve attended a great many cartoonists' events around the world. Bring together men and women who draw cheeky pictures for a living, essentially refining the impulse of the school pupil making illicit doodles in the back of their jotter, and any semblance of solemnity gets thrown out the nearest window. But last year we were invited to convene under the kind of security measures normally expected for diplomats. And the elephant in the room was always the same: Charlie Hebdo.

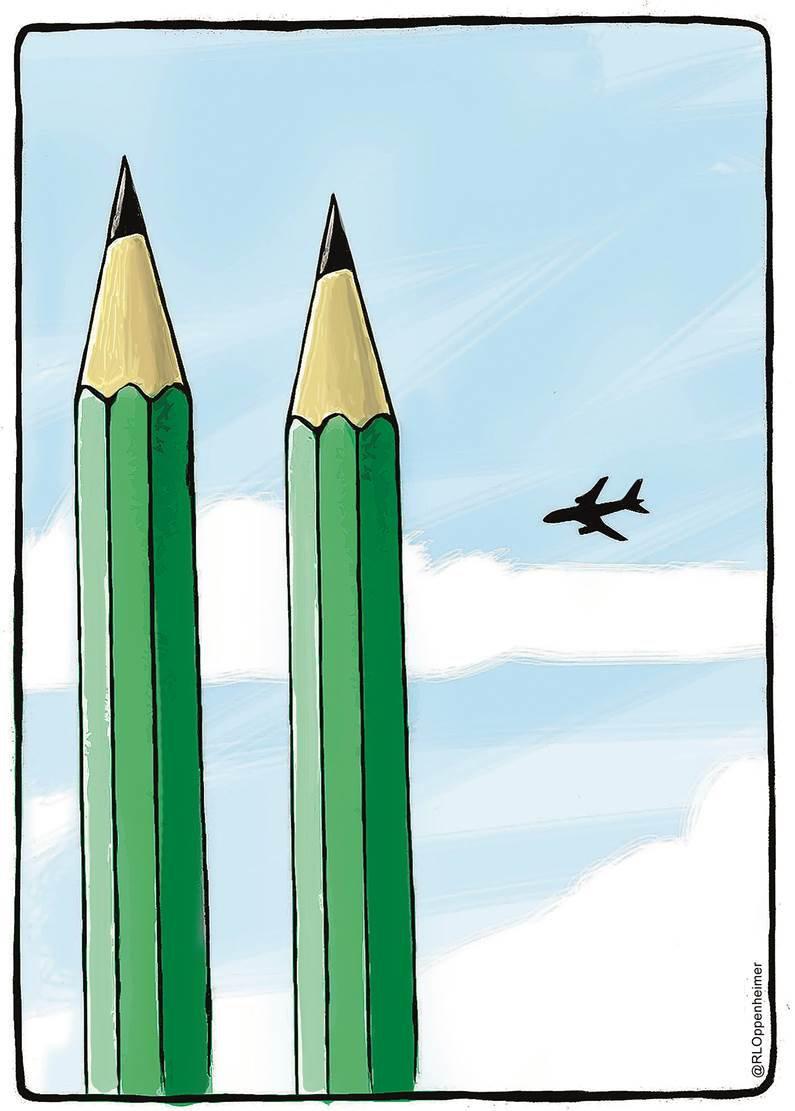

On January 7, 2015, a hitherto obscure French satirical magazine read by a few thousand people was targeted by terrorists and suddenly recast as a cause célèbre, trending on Twitter for days, in receipt of multi-million Euro donations and showy expressions of solidarity from world leaders.

For a moment, cartoonists were placed centre-stage, our particular brand of often blunt, sometimes vulgar satire debated as #JeSuisCharlie became a rallying cry for those who prize freedom of expression while others questioned whether or not the cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo had gone too far in lampooning the Islamic extremists who’d been threatening them for years.

Inevitably, greater crises and bloodier atrocities captured the world’s attention – not least, the Syrian refugee exodus and the massacre of November 13 in Paris, aspects of which situations were mocked in the pages of Hebdo and the magazine criticised for doing so. Despite their losses and the transformation undergone, Hebdo had somehow managed to resume its role of the disreputable underdog nipping at French society’s ankles.

Meanwhile the effect of the attack was felt throughout the cartooning profession. A global conference at le Mémorial de Caen, Normandy was postponed for six months and finally took place behind a ring of steel. Armed officers attended the convention of the American Association of Editorial Cartoonists in Columbus, Ohio. Those attending the annual cartoon festival in Shrewsbury last April had to give an account of their careers to local police in order to identify potential security concerns. (It’s an odd experience, raking through past portfolios and old social media posts, trying to find something that could conceivably excite a jihadist.)

Like hundreds of grieving colleagues, I drew and posted a cartoon in the days after January 7. I didn’t lose friends that day but I lost friends of friends. Perhaps most respected among those who perished was the cartoonist Georges Wolinski. I remember a warm welcome from Wolinski during one visit to France with a large group of Scottish cartoonists, each of us given a cigar. Afterwards we were assured this was not typical behaviour from a man who could be prickly at times.

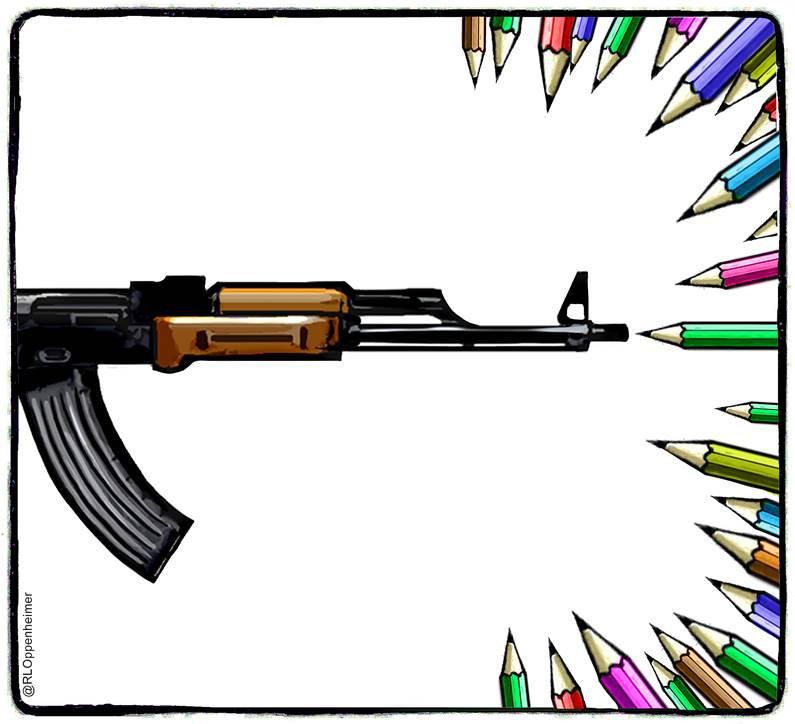

Hebdo’s editors had been tried and acquitted of racial hatred in 2007 and their office firebombed in 2011, after they had published cartoons depicting the prophet Mohammed. So despite the imagery of broken pencils and bloodied drawing tables that proliferated during the first weeks of January, support for Charlie Hebdo was neither unanimous nor unqualified. Had they been unconscionably foolhardy in their repeated portrayal of the Prophet? Why keep “punching down” on a disenfranchised minority within France?

Creator of Doonesbury Gary Trudeau, graphic novelist Joe Sacco and political cartoonist Khalid Albaih were just a few of the creators who publicly questioned the quality of the Hebdo cartoons and the validity of their satire. There was a split among the PEN organisation when the magazine was honoured at an awards dinner in New York, with many high-profile authors boycotting the event.

Elsewhere cartoons were being weaponised, as at the pathetic Muhammad Art Exhibit & Cartoon Contest in Garland, Texas in May. Organised by the so-called American Freedom Defence Initiative, the event drew the attention of two would-be assassins who were almost immediately shot dead by police.

I object to the recasting of all cartoonists as obnoxiously militant, Voltaire-quoting agents provocateur. We did not seek it, but the role of soldiers in a “clash of civilisations” has been thrust upon us. A better metaphor might be canaries in the coalmine.

However, the Charlie Hebdo atrocity was undoubtedly the most high-profile and deadly attack on cartoonists ever seen. It was exceptional and sits apart from a wider and more pernicious trend of persecution by governments. An easy measure for the level of freedom a cartoonist enjoys is how much harassment he or she can expect after drawing a cartoon of their nation’s leaders. And if it can be demonstrated that cartoonists are in jeopardy, you can rest assured that journalists, commentators and oppositional voices of every stripe are too.

Such is the case in Malaysia where Zulkiflee Sm Anwar Ulhaque, pen name Zunar, draws cartoons of Prime Minister Najib Razak, excoriating a corrupt regime festooned with misappropriated riches. Zunar’s office has been raided, books of his cartoons confiscated and his website and social media have been disrupted by the police. In recent months he’s lodged a legal challenge to the nine counts of sedition currently levelled against him by the Malaysian government. The case relates to Twitter posts he made about the imprisonment of opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim. If found guilty he could be jailed for 43 years.

Iranian artist Atena Farghadani used Facebook to share an image satirising her country's parliament as they legislated on reproductive rights. For making a drawing that portrayed politicians as apes and cattle she was detained, tried and given 12 years and nine months in prison. In protest at the abuse meted out by her captors, Farghadani has resorted to hunger strike, despite suffering a heart attack and contracting a lymphatic illness. After shaking hands with her defence lawyer she was further charged with “indecency”, subjected to the horror of a “virginity test” and may have her sentence extended further. Farghadani’s desperately grave situation is the top priority of Cartoonists Rights Network International (CRNI), the human rights organisation that works in defence of cartoonists. She was the recipient of the CRNI Courage in Cartooning Award in 2015.

Within the space of less than one month, fellow Iranian cartoonist Hadi Heidari as well as Tahar Djehiche of Algeria and Jiang Hefei of China were all jailed in their respective countries. In Thailand, Sakda Sae Iao, pen name Sia, has been warned by the country’s National Council of Peace and Order that his work “causes damage” and he should be “prepared for lawsuits”. Turkish President Recep Erdo?an has taken multiple cartoonists and satirists to court seeking hefty damages for their “insults”. All this, in the same year as the world’s top brass marched through Paris under the “Je suis Charlie” banner.

As if to compound our sense of loss we discovered that one of Syria’s best cartoonists, Akram Raslan, who CRNI and others had been trying to locate since his abduction in 2012, had died in custody, his frail condition possibly a result of torture. You can add to that a long list of cartoonists currently working in exile, driven from their homes by the threat of violence or censure. It’s undeniable that none of these outrages would occur unless cartooning had an inherent communicative power that troubles those who have cause to fear dissenting opinion.

Primarily visual, cartoons can cut across language barriers and levels of literacy. They can be readily retooled for the purposes of protest, appearing on banners and posters and in graffiti or used as online avatars. Since they can be processed and understood at a glance, cartoons seem to barge their way into the viewer's mind. So when it belittles a vaunted leader, breaks a social taboo or inverts a piece of received wisdom, the cartoonist’s jibe arrives first with the shock of an impudent slap and then, hopefully, an outburst of laughter.

The cartoonist’s métier is contrarian. It’s certainly a lot easier, if not funnier, to compose a cartoon from a position of negativity – anger, disgust, scorn – than from the sunny climes of optimism.

This aggravates the cartoonist's intended targets – or, perhaps more pertinently, their supporters. In 2014, I curated an exhibition of international cartoons on the independence referendum, which toured five venues around Europe. Among the exhibits were anti-Union strips by Greg Moodie, now familiar to readers of The Sunday Herald's sister paper The National. Moodie's work has rightly brought him a loyal fan base but also, on one occasion, a death threat sufficiently serious to be taken to the police.

I also included anti-independence cartoons by Steve Bell of The Guardian, an artist who almost daily portrays the Prime Minister as a filled prophylactic with nary a flicker of acknowledgement from the Tory faithful. But the infamous “incest and country dancing” instalment of his If … strip ahead of the General Election, which featured Salmond and Sturgeon, prompted thousands of online responses, including 300 complaints, among them accusations of racism and hate speech. The question – how many of those involved had proclaimed “Je suis Charlie” a month or two before? – remains unanswered.

Then in November, cartoonist Dave Brown of The Independent wrote in defence of Stanley McMurty aka Mac in The Daily Mail after a cartoon on open borders seemingly redolent of the worst Nazi propaganda prompted calls for his dismissal, the go-to solution when liberal sensitivities are bruised in our Twitter-fuelled age of permanent indignation. But as Brown put it, “we do nothing to champion free speech when we pick and choose who to support based on the colour of their politics”.

In my own view the only appropriate response to a cartoon that offends is another, better one making the counterpoint. I’ll always prefer the immediacy of a strong image over the nuance of prose – especially in an online world where people want to view more and read less. We know visual humour thrives on social media. If political cartoonists didn’t exist we’d need to invent them, perhaps under some buzz-wordy title like “memetic content generators”.

Despite the enduring power of their work, political cartoonists have had to fight a rearguard action as their traditional platform of the opinion page has become increasingly unreliable. Around the world, news outlets are using fewer cartoons, less prominently and paying lower rates for them. The Scottish press has just one daily political cartoon left, Steven Camley’s in this paper’s other sister title, The Herald. As salaried designers, journalists and editors battle to retain their positions, it’s little surprise that the use of freelancers has dwindled. In the last few months I’ve spoken to a range of Scottish cartoonists, animators and comic book artists for a podcast called Drawn Out; one common thread from the conversations is that, as never before, cartoonists must be self-starters and willing to diversify beyond traditional formats.

Reaching their audience in new ways without the filter of an editor, on a schedule and with a frequency of their own choosing, has given cartoonists unprecedented levels of creative freedom. And it may be that a new golden age is just around the corner, when editors and programmers rediscover the appeal and impact of cartoons. But increasingly the profession is made up of artists working in isolation and therefore exposed to risk. Their contributions, welcome or not, are a sign of robust health and confidence in a democracy. For these reasons CRNI is taking bigger steps than ever before to defend the life, liberty and human rights of cartoonists wherever they are threatened, expanding its board and establishing a new team of global representatives. I’m proud to be part of this effort.

Here’s to a happier New Year wherein hope and especially humour regain the upper hand over hatred and fear.

Terry Anderson is a professional cartoonist based in Glasgow. He is a CRNI board member and their rep in Northern Europe. For more about the organisation and to donate in support of their work visit cartoonistsrights.org

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here