IN September 1994 a £4 million plan was hatched to make Glasgow’s George Square less cluttered and more open. Part of it involved relocating the central statue of Sir Walter Scott, which for 150 years had stood atop an 80ft high column, to the side of the square.

Council leader Pat Lally suggested that Edinburgh-born Scott be replaced by someone more relevant to Glasgow. “It’s just an idea at the moment,’’ he said. “The monument is being moved and I thought this would be a good time to see if we wanted someone else up there. I am sure the people of the city can come up with a person from Glasgow’s history’’.

Opposition Conservatives laughed at the suggestion and made clear their hostility to any notion that Red Clydesider John Maclean might replace Sir Walter. The architectural historian Gavin Stamp denounced plans “to tamper with this central civic urban space by moving the statuary about and casting some historical figures to outer darkness”. The Scott monument was not only “magnificent”, he said, but actually pre-dated the one in Edinburgh.

Read more: Herald Diary

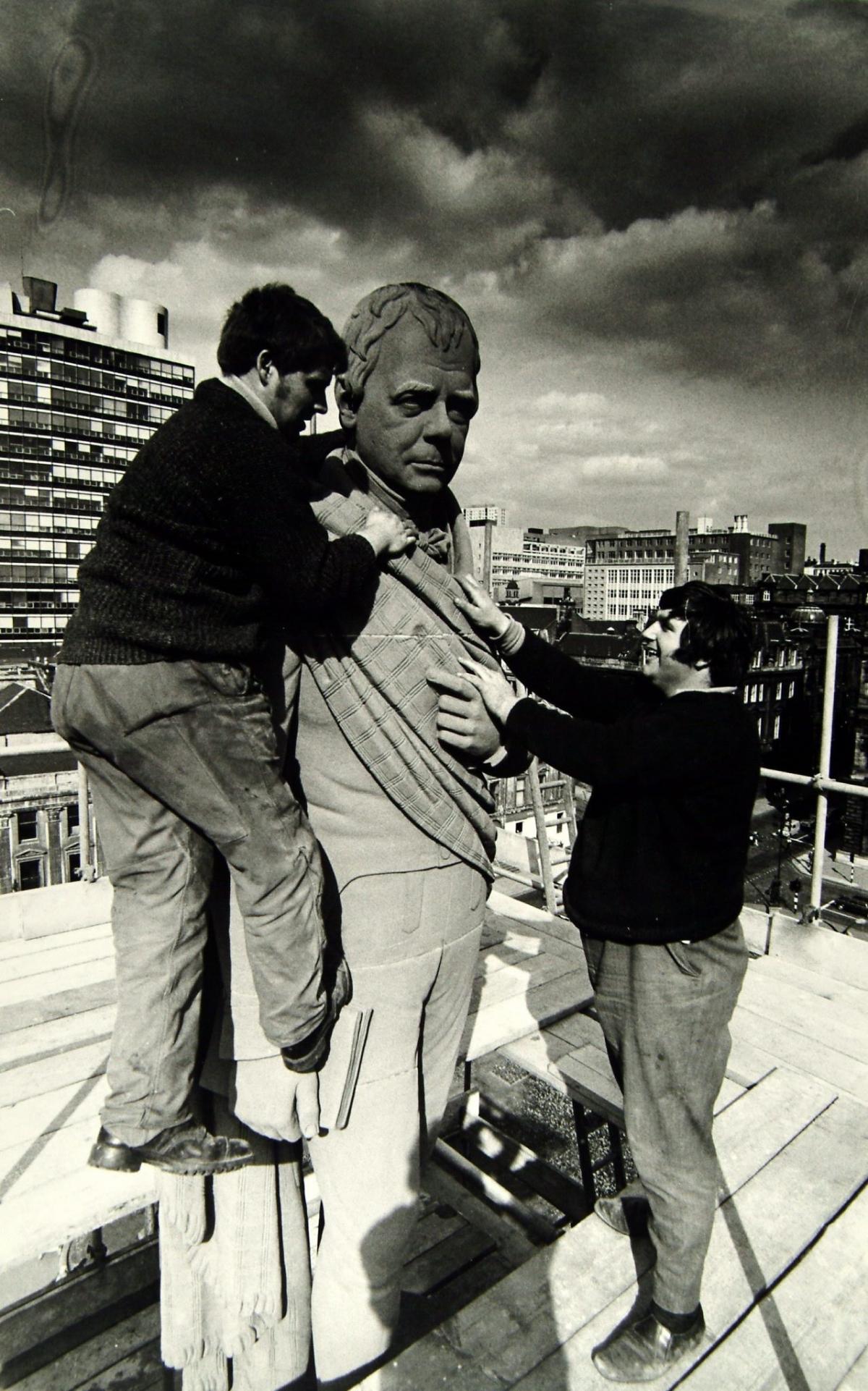

As it turned out, Sir Walter’s statue -– seen here being cleaned in 1970, and up close in 2008 – stayed where it was. It is still there today. That isn’t to say that it has always enjoyed universal acclaim. Critical remarks, to take one early example, were made in a book, Glasgow 1901, by “James Hamilton Muir” (in reality, a composite of three young Glaswegians: the artist Muirhead Bone, his brother James, a journalist, and the lawyer Archibald Charteris).

An extract from the book, re-printed in Alan Taylor’s Glasgow The Autobiography (2016) noted that George Square echoed London’s Trafalgar Square, with “the same central monument, the same weary desert of paving stones, the same feckless designing of the spaces.”

The Scott monument was quite as dismal as Nelson’s. “To set a ‘faithful portrait’ of a great writer on a pedestal eighty feet above the street level, surely this is a form of strange torture, survived from the Middle Ages,” they wrote.

“At the head of the great column only a great symbol – a great gesture – is permissible, although an emperor standing guard over his realm might also be a motive sufficiently dignified. But to hoist to this height a man accustomed in life to walk the streets like any other of us, one to whom close observation of his fellows was a real daily need – this offends all that is just and appropriate”. The statue was not a symbol of enduring greatness, they concluded: “It is simply, like Nelson’s, a man on the look-out tied to the mast-head”.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here