Barrie Cook, painter and teacher

Born: May 18, 1929;

Died: July 15, 2020.

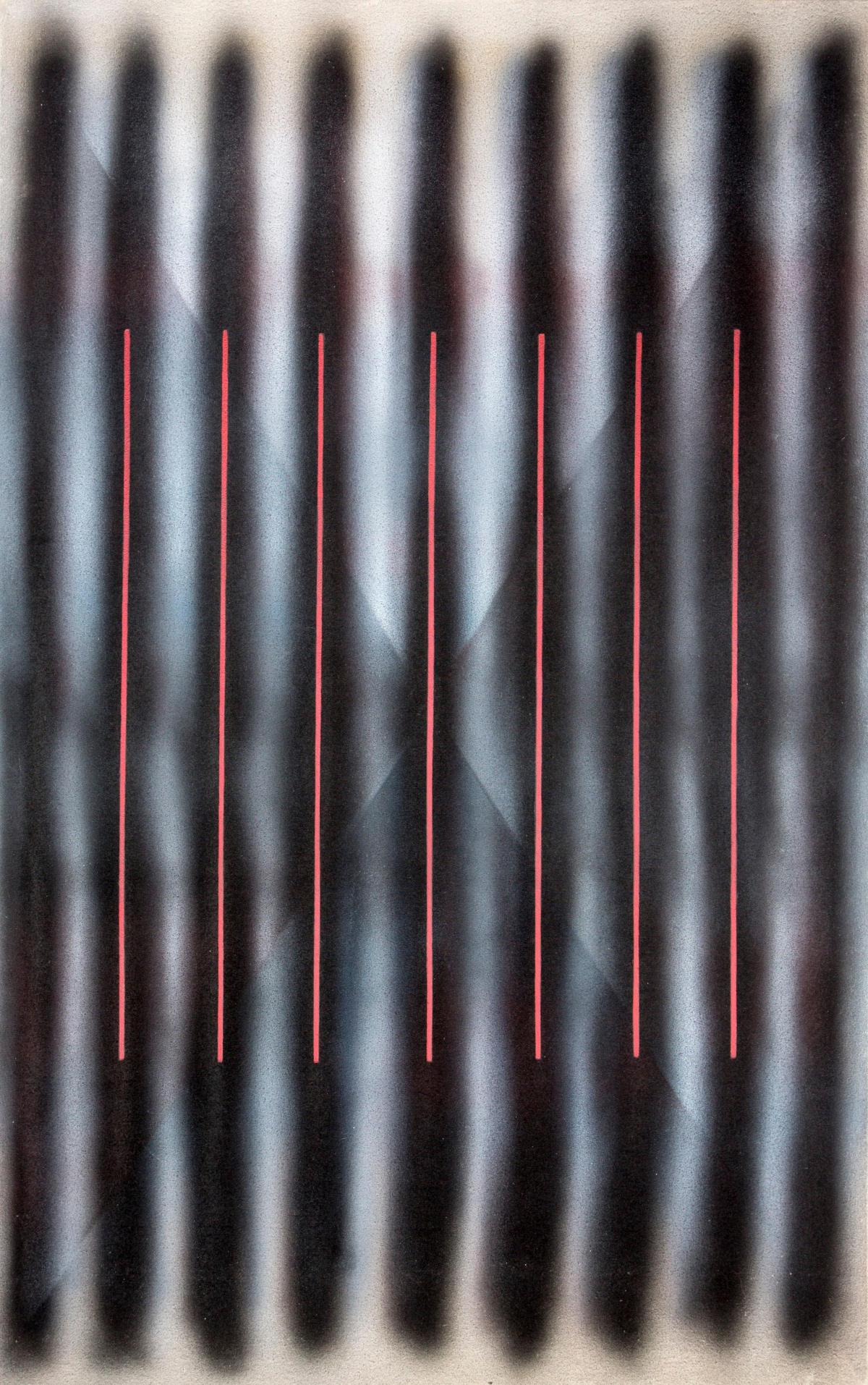

FROM the outset of his career Barrie Cook, who has died at the age of 91, championed the technique of spray-painting, a working method with few notable adherents. He established this way of working as a compelling, respected and versatile mode of expression in a fine art context.

Cook was one of Britain’s most distinctive abstract painters, a man of great integrity and creative energy, dedicated to his work. His abundant love for his wife Mary was ever present.

“My paintings now refer to themselves,” he once wrote, “the importance is to evoke some stirrings within the spectator’s subconscious”. It was crucial that his paintings be free from a literal narrative and for their expressive force to exist as a vehicle for meditation and contemplation.

Narrative significance was not the aim, but moreover the ability to offer the viewer an opportunity to reflect and respond to the essential trait of each painting: its ambiguity.

His critical-creative engagement with each canvas provided the viewer with a deep sense of visual intention which gave his work spirituality and authenticity. For this reason Cook’s work has occupied a distinctive position within British Art for over 40 years.

Birmingham-born Barrie Cook attended Birmingham College of Art between 1949 and 1954. His formal training underpinned his technical skill but such traditions encouraged his preference towards spray-painting, or as he put it, to “break the habit of brush-stroke mentality” and to escape the potential clichés that arise from a “monotony” of technique”.

He acknowledged the formative artistic influences of former servicemen Adrian Heath and Harry Thubron. He was drawn to the latter’s experimental instinctive practices. Sonia Delaunay, Frank Stella and Joseph Albers are also amongst his personal pantheon, their influences well hidden in his own fusion of material.

Through Heath, Cook was introduced to Terry Frost (Heath had taught Frost while both were PoWs at Stalag 383). Cook and Frost became firm friends.

After graduation Cook taught at Bourneville Boys technical School for ten years and lectured at Coventry College of Art until 1962. He was Head of Fine Art at Stourbridge College of Art (1969-1974) and was awarded the prestigious Gregynog Fellow in Fine Art Painting at Cardiff College of Art.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s he had several prestigious solo and group exhibitions, at Herbert City Art Gallery, Camden Art Centre, and Axiom Gallery. His iconic exhibition of “Large Paintings from Black to White” was curated by Bryan Robertson at London’s Whitechapel Art Gallery, in 1975.

He continued to work on a dramatic, powerful scale, painting as well as any of his contemporaries at that time. His strategy was to use formal geometric structures, coolly abstract, often in series, with radiant light expressing a sense of transcendent spiritual optimism.

His reputation, like the size of his paintings at the time followed an upward trajectory, with a number of one-man shows at Oriel Gallery Cardiff, National Museum of Wales, University Gallery Leeds, Glasgow’s Third Eye Centre, cumulating in a monumental show at Serpentine gallery in 1988. This exhibition was a defining moment in Cook’s career: a series of paintings which numbered ten in total and were never less than three meters long and four meters high.

Between 1979 and 1983 Cook was Head of Fine Art at Birmingham Polytechnic then returned to Wales where he was Artist in Residence at the National Museum and Art Gallery.

As a child Cook spent many summer holidays in Cornwall. The Cornish coast’s high cliffs and sparkling seas fascinated him, and the coastline influenced many of his earliest paintings. He had never felt particularly comfortable in London’s competitive esoteric art scene. He was very much his own man: a staunch socialist who would not stroke the ego of the art critics. His passion for his spiritual home and his close friendship with Frost brought Barrie and Mary back to Cornwall in 1992.

This move marked a strong contrast to Cook’s creative palette from the industrial sombre hues of the sixties and seventies to what he referred to as “a lightening of spirit”. Not simply in terms of the physical quality of ocean light, but in terms of the intangible qualities of light. He began to use vibrant turquoise, yellow, orange, cadmium and blues. His appetite for the exploration of the profound continued with a new intellectual and emotional chapter. Just as we thought we had begun to understand the paintings Cook invited the viewer to a new set of responses.

He had begun to explore the writings of Karen Armstrong, the notion that God could be both male and female, something of infinite perfection, a pure spirit, of both mother and father. Cook looked at a way of exploring the sublime, creating for himself his own female iconography with a new series of quiet, contemplative canvases, simultaneously channelling this perceived religious wisdom solely through the use of light.

Cook seldom missed a day in the studio. He was a brilliant teacher, a man of integrity, unpretentious, kind hearted, and patient. He was great fun to be around. He loved his family, his garden, and going down the pub for a beer, but, most of all , he loved his wife. Mary died just two days after her husband passed away. Cook is survived by his daughter Francesca, his four grandchildren and five great grandchildren.

LOUISE JONES

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here