AT the beginning of the pandemic, lockdown and restrictions on liberty unprecedented in peacetime were justified as essential to prevent the NHS from being overwhelmed. That ambition was largely achieved, if the test was the ability to handle Covid hospitalisations. But, judged on other criteria, the NHS was strained to the limit, and its most severe test may only now be starting.

That is not to denigrate what has been achieved. It is a mark of the British public’s exceptional regard for the NHS that the overwhelming majority willingly followed the rules – something neither government, policy advisors nor scientists thought would be workable when cases first appeared. Many went further: they applauded frontline workers weekly, raised huge sums for NHS charities, worked tirelessly to support their efforts.

Whatever misjudgments were made by governments, failure to produce immediate funding was not one; additional NHS spending in England by the UK Government led, through the Barnett formula, to Scotland receiving an extra £9.7 billion last year. Approval of Holyrood and Westminster’s responses (with their respective electorates) is, on balance, still high; few people, for example, complain that the money spent on the Louisa Jordan hospital or the Nightingale equivalents in England which were little used was wasted when they consider the possible alternative.

The greatest credit has correctly been given to frontline medical and support staff, who literally risked their lives and made extraordinary sacrifices to treat patients and then roll out the vaccines. But they will need yet more support and resources in the period of recovery.

That is because these successes have been accompanied – inevitably, and without any fault being implied – by the NHS’s inability to perform its normal function. Delayed operations, increased waiting lists and interruption of the normal process of treatment, as well as of tests, screening and other early interventions have contributed to the excess death toll; in a relatively low, recent example, in one week in April there were 749 more deaths than the five-year average, 86 of which did not involve Covid.

Unfortunately, it is likely that much of the damage this reduction in usual NHS care will have done is yet to become apparent. It ought therefore to be the absolute priority of government to ensure that health care not only returns to the norm before Covid, but that the NHS is given the necessary support to eradicate the huge backlog of non-Covid patients.

Since June last year, there has been a four-fold increase in the number of patients waiting more than a year for treatment while, at the beginning of this year, in-patient and day-care admissions were 50 per cent lower than the same period in 2019. These figures are not merely dismal; they are, unless quickly rectified, a recipe for an impending health disaster.

Few would blame the Scottish Government for failing to meet the legal obligations of the 12-week Treatment Time Guarantee at the height of a pandemic. But 12-month waits as the norm are something that must be seen as an emergency with outcomes as potentially serious and damaging, and there must be no delay in coming to grips with the problem.

Increases in A&E attendance (back to around 97 per cent of pre-pandemic levels) are one consequence of the shutdown of many normal services. GP practices, where obtaining an appointment was difficult enough even before the pandemic, have been far too slow in returning to their role, further straining hospitals. Everyone accepts the continued need for caution, but consultation by Zoom cannot become the norm.

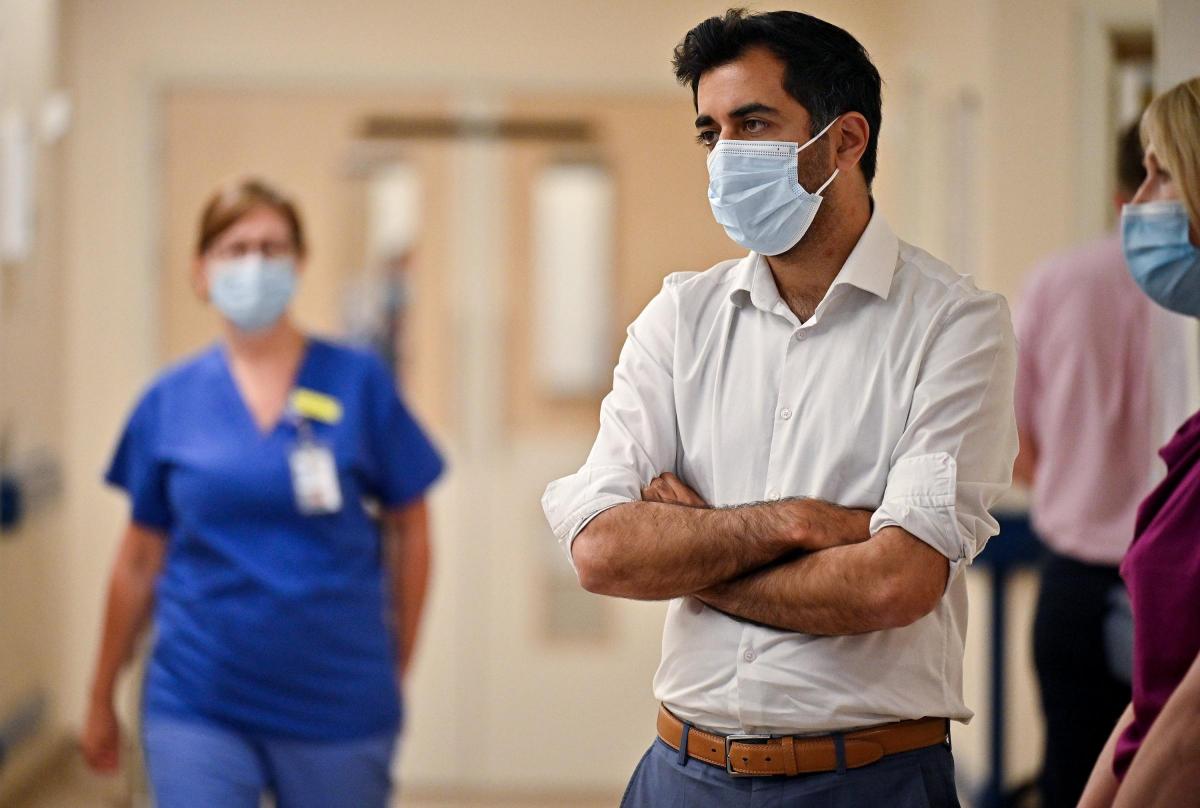

Humza Yousaf, the Health Secretary, has all the levers of a fully devolved health system, but must step up the Government’s game substantially. Botched hospital new builds, the appalling record on care homes, the underspend of extra Covid money from Westminster, the long-standing failure to meet waiting lists and treatment targets and the disgraceful drug deaths are not, to put it mildly, promising precedents. Holyrood has all the powers and funding it needs to improve; it has an urgent imperative and a profound responsibility to do so.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel