We are in uncharted waters.

The energy price crisis triggered by the surge in energy-use coming out of Covid and the war in Ukraine is not only set to send many into fuel poverty but is already transforming our energy landscape.

In this context, one of the big recent debates has been whether doing our best to speed up the wind revolution can bring down those bills now. What are the ideas that might bring its much-vaunted benefits to impact on our bills this coming winter?

Offshore wind is getting ever cheaper over time, promising low-cost energy for the future. Already according to Professor Keith Bell, “the average of costs of electricity from both wind and solar have come down massively in the last 10 years so they are now the cheapest forms of production of low carbon energy or, given the very high cost of gas, of any form of electricity.”

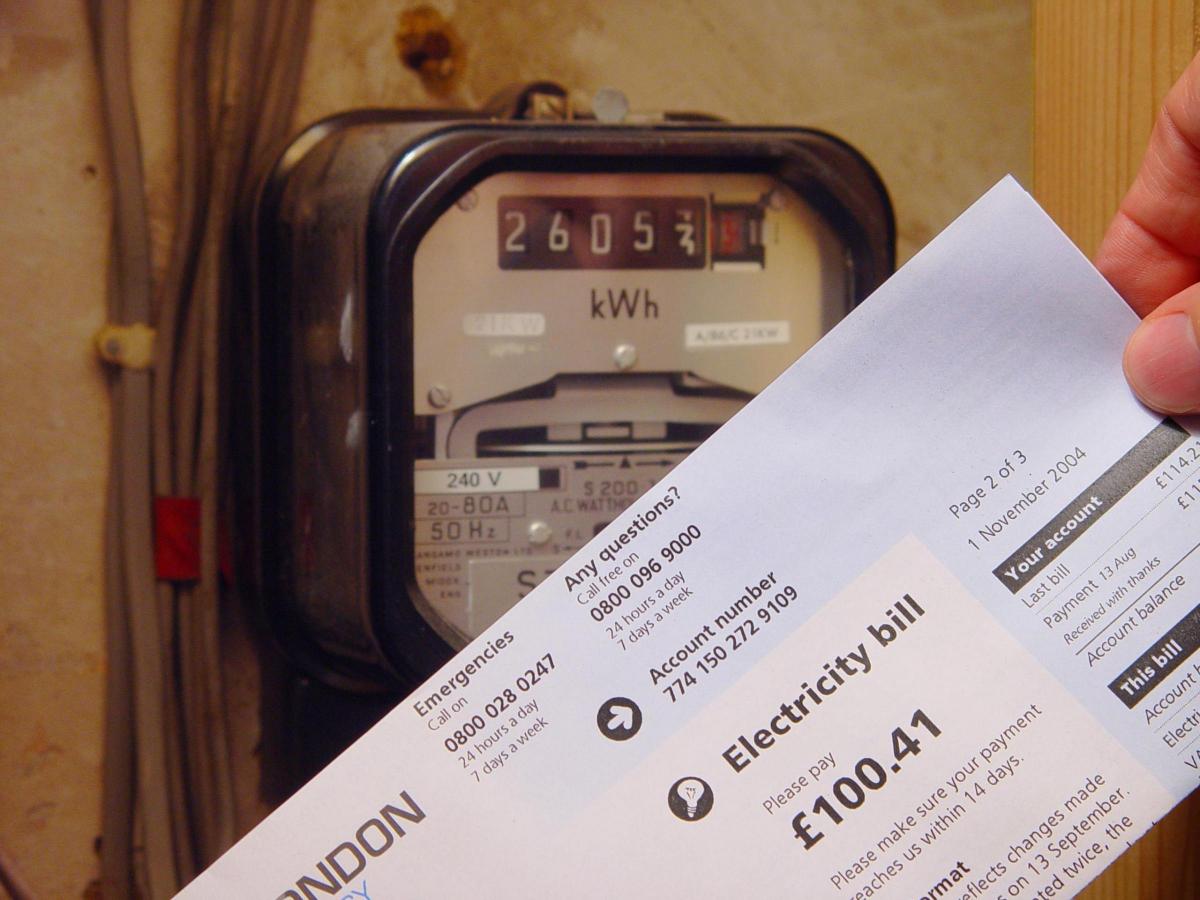

This may sound auspicious for the future, but right now, as gas prices fluctuate, plummeting in recent weeks from eyewatering highs earlier in the year, one of the questions is can it make a difference to our bills now? In fact, it already is - but compared to huge bills forecast for the coming years, a unit price cap that would lead to an average yearly bill of £2500 this winter, the current benefits are tiny.

The benefits of renewables are hobbled by the fact that the price of the electricity generated by them is determined by the wholesale price of gas – an extraordinary situation given that only 40 percent of UK electricity supply is gas generated and in the first quarter of this year 45 percent was generated from renewables.

One of the ways, however, customers can, and already do, gain benefits from renewables is through the payback from deals that exist with some suppliers which effectively guarantee a price, called contracts for difference. When energy prices surge above the agreed price, as they have done lately, suppliers on these contracts pay back the difference to the UK Treasury.

Because prices are relatively high even now, such suppliers are currently paying back. In August, when gas prices were at a staggering high, the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit calculated that if wholesale gas prices remained high,the projects awarded contracts for difference this summer would save £7 billion, or over £100 per home.

Energy analyst, Thomas Edwards at Cornwall Insight observed that the current round of contracts will probably pay back “consumers for much of their lives”. Taking August gas prices, he calculated that, between October 2022 and January 2023, renewables projects with a contract for difference could be set to pay back £729 million. Wind projects alone, according to Edwards’ calculations were set to pay back £473.5 million. But as the price of gas drops, so do these paybacks.

Meanwhile, the energy market, as recent months have shown us, is hugely complex in multiple ways – and while some windfarms are currently paying us back, other renewables and nuclear companies are raking it in as a result of the coupling of gas and electricity prices. Some windfarms, generally older onshore farms, are receiving a windfalls – and at the same time raking in subsidies. This has provoked outrage.

Liz Truss’ government announced last month that it planned to introduce new fixed price contracts for existing renewables generators. The plan was based on an idea by UKERC director Professor Rob Gross, who, in a paper earlier this year, asked, “Can renewables and nuclear help keep bills down this winter?” When the paper first mooted the idea in April, the authors described it as “unorthodox” and “controversial” - but such is the scale of the crisis that it has now been embraced.

“Our idea,” said Gross, “is to try to get as many of our existing nuclear power stations and older wind farms under an arrangement called a contract for difference (CfD). This provides a long run fixed price contract for their electricity. New wind farms already get a CfD and so will the new nuclear power station under construction. But for now, most of the wind and nuclear stations get paid wholesale prices. Since the price is so inflated, because of the price of gas, the scheme could save billions. One reason it could be attractive is that the mechanisms to do this already exist.”

The idea is no longer so controversial. “Now," he noted, "we see interventions in markets happening in countries across Europe and a debate in the UK. So I would not describe it as unorthodox any more.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel