He leads arguably the most successful party in the democratic world. Mark Drakeford has just led Labour to another win in Wales, completing an unbroken century of election victories, if not power.

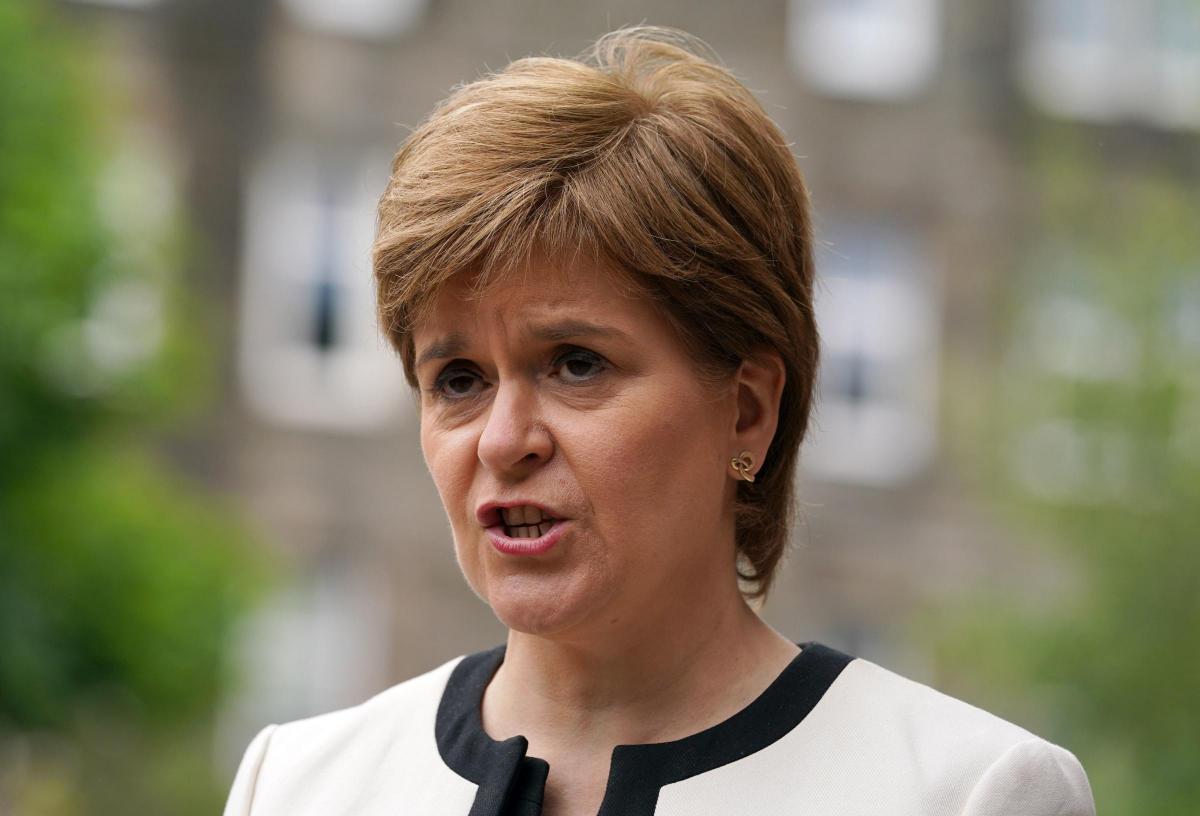

The first minister commands half the seats in the Senedd Cymru and, polls suggest, has the highest net approval ratings of any leader in the UK, including Nicola Sturgeon.

And yet nobody seems to want to listen to him. Not outside Wales anyway.

This week Mr Drakeford unveiled a 20-point plan to reform “our union”, to save what he called a ‘fragile” UK from itself. He warned Boris Johnson and his UK ministers were acting “aggressively” and “unilaterally”, ignoring devolved governments in Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast. He called for a “reset”, for a new UK, a voluntary, constitutionally guaranteed “partnership of equals”.

The response? Tumbleweed.

The Drakeford plan was barely reported in England and Northern Ireland and not at all, as far as I can see, in Scotland. The UK Government shrugged off the work, an anonymous PR person telling the Western Mail that “choosing to prioritise constitutional issues in the middle of a pandemic is an irresponsible and unwanted distraction”.

READ MORE: The rise of Welsh nationalism

The same government the next day secured planning permission to unfurl a Union Jack down the side of its Cardiff tax office, a city centre tower block. The flag will be eight storeys high. Eight. Storeys. High.

So Mr Drakeford gets ignored. And the skyline of the Welsh capital is turned red, white and blue. Now that tells us something about Britain, doesn’t it?

Unionism is in crisis, an intellectual crisis as big and as obvious as that vulgar Cardiff Union flag.

This is not new. It has been the case at least since the victors of the first indyref emerged, blinking and dazed, from their 2014 victory parties. Those campaigners had saved their Britain, or at least given it a stay of execution, but only by undermining some of the key ties which once knitted our curious multi-national state together.

Their Project Fear worked, just. But telling Scots, for example, that the currency they shared with the rest of the UK would automatically belong to rump Britain had consequences. “This is ours, not yours,” went the subtext. “And we’ll take it away if you go.” That, for Scottish nationalists, summed up what they saw as the reality of an unequal union.

Since 2014 unionists in Scotland and England have appeared incapable of producing a coherent, inclusive pitch for keeping our multi-national state. They have not even looked able to have an intelligent conversation of how they would go about developing one.

READ MORE: The death of traditional unionism

They are either still waging Project Fear, re-fighting indyref1, or, trying to drum up British “one nation” nationalism, unleashing some ugly chauvinism as they do so. Both tactics are, essentially, failing. Smart unionists know this.

Fear, after all, has its limits as a tactic. Sure, independence can be scary. Change always is, but it tends to come whether you like it or not. Brexit means the status quo which more cautious voters backed seven years ago now longer exists. Some pro-UK figures hope some Scots might get antsy about indy after Brexit, that this would be too much change, too much risk. And some surely will. But there is only so long you can keep people scared.

A UK based on British nationalism, meanwhile, is hardly a serious or winning short-term proposition when most residents of Scotland and Wales see themselves as Scots or Welsh only.

Some pro-UK politicians this week celebrated a poll that put “No” to independence ahead, but within the margin of error. Nudging “separatism” below 50% is hardly a big success for a political creed whose basic premise – Scotland in a union – was once so deeply ingrained it went unchallenged for decades.

If those who wish to save Britain were serious about doing so, they would be pouring over Mr Drakeford’s proposals.

After all, this is a rare politician in these islands, one who can successfully sit astride a constitutional wedge issue. Mr Drakeford transcends the kind of unionism v nationalism divide which defines Scottish politics.

The Labour leader taps Welsh nationalist sentiment in a way his Scottish party colleagues no longer can – but still believes in the UK, albeit a reformed one. Some 40% of voters who support independence back his party. That is nearly as many as those who cast their ballots for Plaid Cymru two months ago.

The Drakeford plan includes a second chamber representing what he calls the four nations of the UK (he includes Northern Ireland in this) – something mooted in Scotland before. What he is proposing is akin to federalism.

READ MORE: British nationalists want to partition Scotland

The pandemic recovery means an independence referendum is quite far off. Pro-UK campaigners have time to regroup, to rethink their long-standing aversion to a political system that fully reflects Britain’s national diversity. Will they take this opportunity? That Cardiff Union Jack suggests not.

British nationalists – and they run the UK now, let’s be frank about that – think federalism is a slippery slope to the break-up of what they see as their nation.

I’ve come across this before. I remember speaking to federalists in Catalonia long before that nation – or region, for Spanish nationalists – found itself locked in to a bitter constitutional crisis that saw police bash the heads of voters and leading independentistes locked up.

A downbeat Catalan socialist called Ferran Pedret summed up how federalism was viewed in Iberia. “Me, as a Catalan,” he told me back in 2015, “I can live in a state that is not the nation state of the Catalans. You can think of the Spanish as a nation of nations. But Spanish nationalists don't agree. That is one of our main problems.”

It is one of the UK’s main problems too. It can sometimes look like Britain is more comfortable with its pluri-national nature than Spain. I am not sure it is. We keep talking about the Scottish Question. But unionists need to come up with an answer to the British Question: how does the UK state reflect its constituent nations? Mr Drakeford, at least, is trying to do so.

Our columns are a platform for writers to express their opinions. They do not necessarily represent the views of The Herald.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel