The way we work is changing. Millions now work from home, and the shift is accelerating daily. It is the biggest upheaval in work since the Industrial Revolution. Writer at Large Neil Mackay looks at how life has altered and meets the woman behind ‘the nowhere office’

IF you want a vision of the future of work, look no further than the Campbell family. Half the Campbells are part of the new wave of white-collar homeworkers, able to earn a crust wherever they like: from an office, cafe, or even bed. The other half are stuck in the old world, on shift and expected at work when their boss says so.

Rose is 25 and works in digital advertising. Since the pandemic, she’s rarely been into the office. It is a seller’s market for people with her skills – job websites are filled with advertising posts. Rose’s boss wanted her back in the office, but she threatened to quit and find work elsewhere if she had to come in every day.

Her boss capitulated and now she is only in once a week for big team meetings.

Rose’s dad, Patrick, worked in public relations but quit during pandemic. “It just dawned on me,” he says, “how bloody awful the office is, so I took a package and left.” Patrick is now self-employed. Most days, he works from his attic.

He earns slightly less than before but says he has never been happier.

His wife, Kelly, is a teacher. Her working life hasn’t changed – going to work means going to school. Their other daughter, Suzanne, is still at university but works part-time in restaurants on zero-hours contracts. Like her mum, she comes to work when she

is told. This average Scottish family shows just how rapidly work is changing … for some. We’re at the beginning of a moment that’s being defined as “the nowhere office”: a trend which sees mostly white-collar workers, often in creative industries, jettisoning old ways of working post-pandemic. They are either in companies relatively relaxed about staff working from home for part or even all the week, or freelancers able to work wherever they please.

The great resignation

The “great resignation” lies at the heart of these changes. Millions across the West quit their careers during the pandemic – often opting to retrain for dream jobs, or downsizing for happiness. In London, due to white-collar concentration, half of all employment is now either based at home or is “hybrid” work, where staff go into the office a few days a week. In Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, the figure is about 20 per cent. New research shows hybrid working is more popular in Scotland that anywhere else in Britain.

A recent poll of UK corporate leaders by the Centre for Economics and Business Research found increased remote working led to better customer satisfaction, higher productivity, and happier staff.

In the West, 75% of global companies have now introduced hybrid working in some form. Scholars of social trends say what is happening to the world of work now is as seismic as the invention of “the weekend” during the Industrial Revolution.

Julia Hobsbawm has been described as “one of the foremost thinkers” in Britain when it comes to running businesses. She is chair of the Workshift Commission at the leading think-tank Demos, and heads Editorial Intelligence, a company specialising in networking and “social health” within industry – in other words, how to make workers happier, healthier and therefore more productive.

Hobsbawm is the daughter of the acclaimed historian Eric Hobsbawm, who was a world authority on industrialisation, capitalism and socialism. She has just written The Nowhere Office, a new book investigating how the way we work is changing. Unlike her father – a lifelong Marxist – Hobsbawm is unashamedly “pro-capitalist”.

However, she believes the changes now affecting the workplace will make life better for workers, while also improving productivity and profits. Hobsbawm has also advised UK governments.

Office revolution

THIS moment we’re in, she says, “is seismic for the white-collar workplace. It’s no exaggeration to say it’s the biggest workplace experiment in 100 years”.

There has been nothing so radical as the rise of hybrid working and homeworking – which Hobsbawm groups together under the umbrella term “nowhere office” – since WK Kellogg (the Cornflake king) experimented with six-hour days in 1930 to improve workers’ lives and boost productivity.

Hobsbawm draws parallels between the post-pandemic revolution in the world of work and the immediate aftermath of the Second World War. Both are moments of “reset”.

The ‘mad men’ years

SINCE 1945, there have been four distinct periods of work in Britain. The first phase,” says Hobsbawm, “was between 1945/77.” These were “the optimism years”.

She adds: “The years of rebuilding, epitomised by a rather simple, almost wilfully blind, ‘let’s-not-worry’ attitude to issues like fairness, inequality, sexism and racism.

It was ‘let’s just get on with consuming’. These were the mad men years, and also the years when technology was at the back of the room.”

Next, from 1977/2006, came “the mezzanine years” – the halfway stage between the “mad men” period and now. “This was when technology was coming in, as indeed were sensibilities around women’s rights at work,” says Hobsbawm.

It was also the time when we started thinking about work-life balance.

Then came “the co-working years”. Think of the appearance of all those offices across Britain filled with multiple small businesses with just a few staff, sharing space, equipment and ideas. This period was marked by “the arrival of the smartphone and the enshrinement in our psyches that freedom and mobility mattered”.

However, until the pandemic hit, the office remained a “palace of presenteeism”. The notion of mass home or hybrid working was basically absurd.

Then, come 2020, “it all ground to a halt with the pandemic, and ushered in this new phase – the nowhere office”.

Class divide

CLEARLY, there is a huge class and skills divide when it comes to who benefits from the nowhere office. Nurses, police, chefs, supermarket staff – nobody in careers fixed to a physical place will ever be home or hybrid workers.

The main beneficiaries are white-collar staff, often young and technically skilled. They are mobile because all they need is a laptop and phone.

For those able to change, though, “office life won’t be five days a week, nine to five, anymore”. Until the pandemic, “the norm was to be present, visible and monitored by a manager”.

“The first obvious point about the nowhere office is that it’s shifted from presenteeism to remote-based, hybrid-based, work-from-home, patchwork patterns of working, where a greater degree of autonomy and trust is given to those workers that are, you could put it, the hybrid-haves,” says Hobsbawm.

Frontline workers, and those not in offices, are becoming the “hybrid-have-nots”.

There is an argument to be made that these “have-nots”, says Hobsbawm, “ought to be remunerated more because they don’t have flexibility … There should be a premium for presenteeism if certain jobs have to be done from a fixed place during fixed hours with no agency or autonomy”.

Toxic scenario?

OBVIOUSLY, for the “haves” to really prosper, they need to be trusted by their bosses. Many managers see these changes as a nightmarish scenario where staff go unsupervised – and

that micro-management is half the problem.

Bad leadership, Hobsbawm believes, lies at the root of why modern work has gone so wrong.

Before the pandemic, “work wasn’t working, it was dysfunctional”. She says: “The world of work was unwell. Not for nothing is the phrase ‘toxic workplace’ so established.”

Look how we “obsess culturally”, Hobsbawm notes, on toxic workplaces in shows like The Office. No wonder, 50% of workers are prepared to quit their job if they don’t get greater flexibility – in other words, life free from bad bosses.

The great resignation, Hobsbawm says, is more a “great re-evaluation”. People want “meaning, values, purpose, fairness”, she says.

“The pandemic gave us permission to talk about these things. Bosses have been wrong-footed by the strength of feeling of this shift, that people don’t want to go back to the office the way they did before.”

West vs the rest

WHAT is happening is clearly a Western phenomenon. Many nations don’t have the luxury for such changes. It wasn’t until 2018 that South Korea’s government reacted to the scandal of “Gwarosa” – literally “working yourself to death” – by lowering working hours from 68 to 52 a week.

“It’s absolutely not clear whether the global south or developing economies aren’t just going to eat our lunch and say ‘we’ll take your working week, we’ll give ourselves burnout as we want to earn and consume and do all the things that [Westerners] are now rejecting’ … Certain nations may still chose to work in siloed ways.”

Power to the people

THE Western current trend, Hobsbawm says, is “towards workers having more power”. She believes that work must have “meaning”. But can the idea of the nowhere office really put “soul” into the concept of employment, and give workers genuine clout?

Certainly, work was out of sync with employee values prior to the pandemic. Now there is more focus on “fairness, rest and leisure balanced with good work which is well-managed and has meaning”.

Just think of the increased attention on mental health from HR departments. Bosses are now scared of making people ill.

The flip side, though, sees bosses worrying about negative effects on professionalism – like customer service advisers taking calls at home while their baby cries in the background.

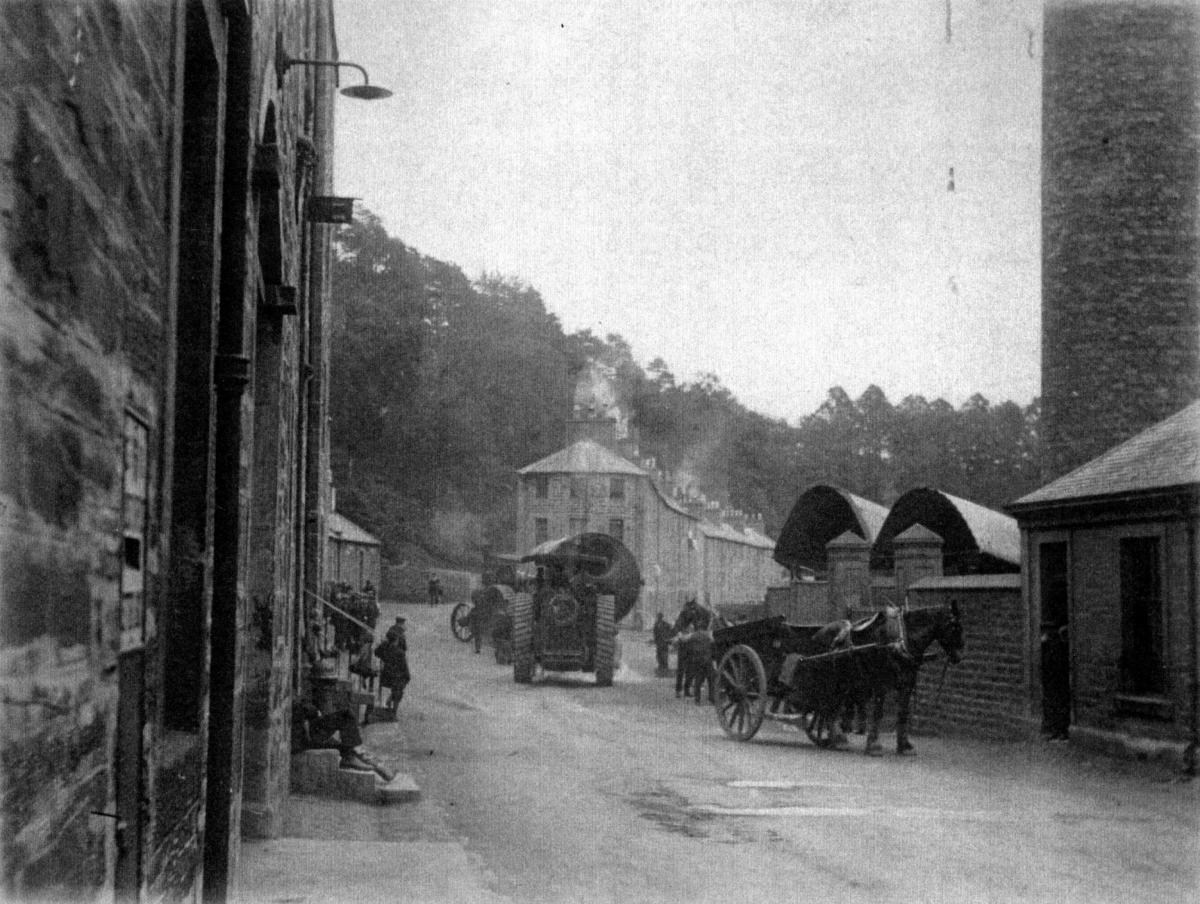

New Lanark 2.0

THE last time Britain had such a “national conversation” was back in the Victorian era when factory owner and social reformer Robert Owen established the eight-hour day at his New Lanark site. The irony is that we have known for generations that better conditions raise profits and productivity. The industrialist Lord Leverhulme advocated six-hour days back in 1918 as it was “index-linked to better performance”. The happier people are, says Hobsbawm, the more productive they are. “Productivity rises and absenteeism drops if workers are consulted and given agency.”

Bad bosses

AS long as bosses get on board, then Hobsbawm feels relatively optimistic about the future. “My beef is with management,” she says. “In fact, anyone who calls themselves a leader. That’s the elephant in the room.”

There are “many failings of capitalism, and of course it needs at the very least reforming”, but Hobsbawm believes it is too simplistic to just blame the free market for workplace misery. The real problem, she claims, is “appalling managers. We worship at the shrine of leadership in a way that’s not healthy or functional”.

Add in breakneck changes in technology and we end up with rotten ways of working. Additionally, HR teams increasingly use “technology to minimise and outsource human interaction which massively magnifies the problem of bad management”.

Dead cities

SO, may of us will escape bad bosses, have more freedom and be more productive. Sounds great. But it’s not all rosy. The rise of the nowhere office obviously exacerbates the so-called “death of the high street”, already hollowed out from shop closures. That may be offset, however, by the way some imagine the future of offices. Those who do go into the office – either full time, or as hybrid workers – will most likely want more than just desks and somewhere to make tea.

The office of the future may include cinemas, gyms and social clubs as work becomes more “experiential”, just as the high street, we are told, must become more about “experience” rather than mere shopping if it’s to survive.

Hobsbawm says there is likely to be a “redistributive element” in cities, with hybrid and homeworking meaning suburbs become more vibrant. “For levelling up – to quote the phrase of the day – the nowhere office is entirely beneficial,” she says. The UK Government, however, wants people in the office, not working at home. “I’m communicating to the Government,” she says, “that they aren’t in the right head space on this. While there may be disruption and pain coming, embracing this new reality is better than sticking their head in the sand.”

The shift away from city centres does, Hobsbawm admits, come with “massive negative effects” such as falling revenues from public transport. Crime may also rise in less-populated city centres.

Digital zombies

WHAT chills many about the rise of homeworking, however, is the possibility that we become increasingly isolated, digital beings, as we lose the social side of work. Hobsbawm says “nobody in their right mind thinks that fully remote working is going to be for anything other than a minority”. She sees the trend taking most workers towards two or three days in the office, with the rest of the week spent working from home. “And those two or three days should be very social.”

Coming to the office, she envisages, won’t be about sitting at a desk and just doing what you could do at home. Journeying to the office will need purpose – and that purpose is “social health”. When staff come to the office there should be “time budgets, and coffee and lunch budgets”. In other words, when workers come into the office, they do so to network and meet people who will be good for business –and crucially they will do that with their boss’s support and approval, as well as expenses to make the meeting worthwhile. Otherwise, why not just work from home permanently?

Changing times

BUT will most bosses buy into this? Won’t they fear losing power and control? It’s already too late, says Hobsbawm, adding: “The winds have changed.” She is constantly contacted by HR teams asking her to advise on how to get bosses “to let go of their rigidity”.

“The word of the time is “agile” – agile in management, leadership and budgets.” That’s the point of the nowhere office, she says. “Now’s the moment to fix all the stuff that hasn’t been working. Let’s be clear: 18 million days a year in Britain are lost to stress. This is absolutely the moment for change.”

Dark side

ALTHOUGH Hobsbawm sees the rise of the nowhere office as a “repudiation” of recent trends such as zero-hours contracts, which she admits “disgust” most people, there is clearly every possibility these changes to how we work encourage the use of casual labour, which will mean loss of rights like holiday and sick pay.

And will nowhere office staff always “be on”, never truly able to switch off for the day? Hobsbawm says: “The left often goes on about pay as if it’s the only denominator of being fulfilled at work.” She believes “the freedom to self-determine and have agency and flexibility” are just as important. Clearly, no trade unionist, and few on low pay, would agree with her.

Hobsbawm believes – though stresses she “could be wrong” – that the changes happening in employment will be of such consequence that “identity politics” in the workplace loses its “centrality”. She sees identity politics as “epitomised by enormous amount of corporate time spent on pronouns”. Evidently, such comments will upset equality campaigners and the trans community.

And what about those unable to enjoy the benefits of hybrid working, like hospitality staff or Amazon employees? There has always been “lots of imperfections and inequalities” when it comes to work, Hobsbawm says. One need only look at the different experiences of factory and office workers down the years. “Inequality is rife through all work, nobody is denying that.”

What is clear now, though, she insists, is that office work is “just a different form of wage slavery”. There are claims that those unable to benefit from hybrid working will weather technological change better than white-collar staff. AI can’t pour a pint, but it can do your accounts. Nevertheless, factory workers will suffer from automation, not PR execs. There are myriad challenges this new future presents – not least that it seems geared towards young people rather than older workers perhaps ill-equipped for change.

But Hobsbawm insists: “We need to remember that work wasn’t perfect before the pandemic – it was inefficient, unproductive, toxic, and stressful. Change is going to happen just as fast as the workforce wants change. That’s a question for the C-suite – managers, leaders, policymakers. Remember the old joke: how many psychoanalysts does it take to change a light bulb? One, but the light bulb has got to want to change.”

Names and some details of the Campbells have been changed at the family’s request

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel