As the Kremlin stands accused of war crimes in Ukraine, Foreign Editor David Pratt who was recently in Kyiv takes stock of the evidence and reflects on where the war is now heading

Every few moments the thump of an explosion reverberated from somewhere not so far away. These were the last days of intense fighting north of Kyiv and soon the Russian forces would be pulling back.

But in their wake, they seemed determined to leave as much death and destruction behind as possible, and in the northern Kyiv suburb of Podil, Russian shelling had already left its ugly mark on the civilian population.

Over the previous few days, the force of the explosions had obliterated one structure in Podil’s shopping centre car park and gutted an adjacent 10-storey building, shattering windows in the surrounding residential tower blocks.

In one neighbourhood, charred and blackened trees and the mangled remains of cars sat alongside a huge crater gouged out of the ground by the impact of the shells and rockets that had landed.

In every block the windows had been blown out and the gable end of one had been sliced away exposing the insides of what had until recently been people’s homes.

Wandering among the rubble I momentarily caught a glimpse of one elderly man who had returned to the bombblasted ruin of his flat to pick up a few remaining belongings.

It was a forlorn task, but then for the people of this neighbourhood in Podil just like countless others across Ukraine, picking up the pieces of their lives will be an altogether greater challenge.

All wars take a terrible toll on the civilian population and Ukraine right now is no exception. Just like the last major war in Europe in the former Yugoslavia, this conflict appears to be being fought seemingly without respect for the rules of warfare that were drafted in the wake of the Second World War and the Holocaust.

After the horrors of that global conflict, prosecutors laying the groundwork for the Nuremberg trials devised the concept of crimes against humanity to protect people against systematic attack.

These codes of conduct put in place after 1945 were an effort to prevent a repetition of the worst abuses of the Second World War. They were, as authors Roy Gutman and David Rieff explained in their seminal book Crimes of War: What the Public Should Know, designed to establish even in conflict, “a firebreak between civilisation and barbarism”.

But in the days following my visit to Podil, which itself has arguably been subjected to a war crime under international law, far worse horrors have surfaced in the Ukrainian towns of Bucha and Borodianka.

On Friday, as rain fell, forensic investigators, clad in white suits, began exhuming a mass grave in Bucha, wrapping in black plastic bags and laying out the bodies of civilians who officials say were killed while Russian troops occupied the town just northwest of Kyiv.

Ruslan Kravchenko, from the prosecutor’s office in Bucha, said they had exhumed 20 bodies, 18 of whom had firearms and shrapnel wounds. He said two women had been identified, one of whom had worked at a supermarket in the town centre.

Since Russian troops pulled back from Bucha last week, Ukrainian officials report that hundreds of civilians have been found dead. Bucha’s mayor says dozens were the victims of extrajudicial killings carried out by Russian troops.

Speaking to Reuters news agency, Bucha’s deputy mayor Taras Shapravskyi said more than 360 civilians were killed and about 260-280 were buried by other residents in a mass grave. He added that there were two parallel trenches dug at the mass grave site, with bodies piled on top of each other in layers.

‘Monstrous forgery’

For its part, the Kremlin has insisted that allegations of Russian forces executing civilians in Bucha are a “monstrous forgery” aimed at denigrating the Russian army.

Russia’s UN Ambassador Vassily Nebenzia told the Security Council last week that accusations of abuse were lies. He said that while Bucha was under Russian control, “not a single civilian suffered from any kind of violence”.

Its defence ministry also issued a statement saying that all photographs and videos published by the Ukrainian authorities alleging “crimes” by Russian troops in Bucha were a “provocation”.

Moscow has even gone as far as to accuse the Ukrainians of staging “fake” killings and hiring actors to play victims, even though satellite pictures showed corpses strewn on Bucha’s streets when the Russians still controlled the town of more than 40,000 people.

But with every day that passes Russia’s protestations have an increasingly hollow ring to them as further evidence of atrocities continues to mount.

Just a few days after the discovery of evidence pointing to the unlawful killing of civilians in Bucha, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy described the situation in nearby Borodianka as “significantly more dreadful”, and warned that more atrocities will likely unfold once full access is gained to cities and communities, some which are still besieged by Russian forces.

“And what will happen when the world learns the whole truth about what the Russian military did in Mariupol?” Zelenskyy asked. “There, on almost every street, is what the world saw in Bucha and other towns in the Kyiv region after the withdrawal of Russian troops,” the president predicted of the southern port city that has been subjected to some of the heaviest fighting and bombardment.

Zelenskyy has already openly accused Russia of war crimes and “genocide” – the gravest of crimes against humanity – and said he had approved the creation of a “special mechanism of justice” under which Ukrainian and international investigators, prosecutors and judges will work together to lay the groundwork for a future war crimes tribunal.

Doubtless the work of such investigators will also focus on Borodianka, a satellite town some 37 miles northwest of Kyiv where few buildings remain standing. These past days, families there could be seen looking for relatives and watching diggers search through the rubble of an apartment block. Most of the building was charred and its middle section had been razed to the ground, leaving a gaping hole.

World leaders, it seems, are in no doubt who is to blame. President Joe Biden has already described his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin as a “war criminal” and said he should face trial.

In France, president Emmanuel Macron said there were “very clear indications of war crimes” in Bucha, and those responsible should answer for them. German chancellor Olaf Scholz, meanwhile, deplored the “terrible and grisly” images and said: “We must unsparingly investigate these crimes of the Russian military.”

Throwing accusations at Russia and its leaders, however, is one thing, but proving guilt over war crimes and holding to account those responsible is something else again.

For many of us looking on at the grisly photographs and television footage coming out of Ukraine it’s probably hard to understand what exactly constitutes war crimes amid such carnage.

‘Grave breaches’

According to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, war crimes encompass a range of behaviours in armed conflict. These include the intentional targeting of civilians, torture, or inhumane treatment, attacking areas that are not part of military objectives and intentionally attacking schools, hospitals, and religious buildings. The International Criminal Court defines war crimes as “grave breaches” of these conventions, which were ratified by all United Nations member states.

War crimes generally refer to “excessive destruction, suffering and civilian casualties” while “rape, torture, forced displacement and other actions may also constitute war crimes”, says human rights and international law scholar Shelley Inglis who has written about war crimes in Ukraine recently for the online media outlet The Conversation.

Travelling across Ukraine recently and given such definitions of what constitutes war crimes, I, like many other eyewitnesses are in little doubt that such offences have been committed. Perhaps the best single indicator of a major war crime is often a massive displacement of civilians and in that regard certainly vast numbers of ordinary Ukrainians have been forced to move and leave their homes.

At railway stations in Lviv, and on the Polish border, on the highways and backroads, an endless stream of humanity is to be found either fleeing for their lives from the scene of a crime or the immediate threat of crimes at the hands of Russian forces.

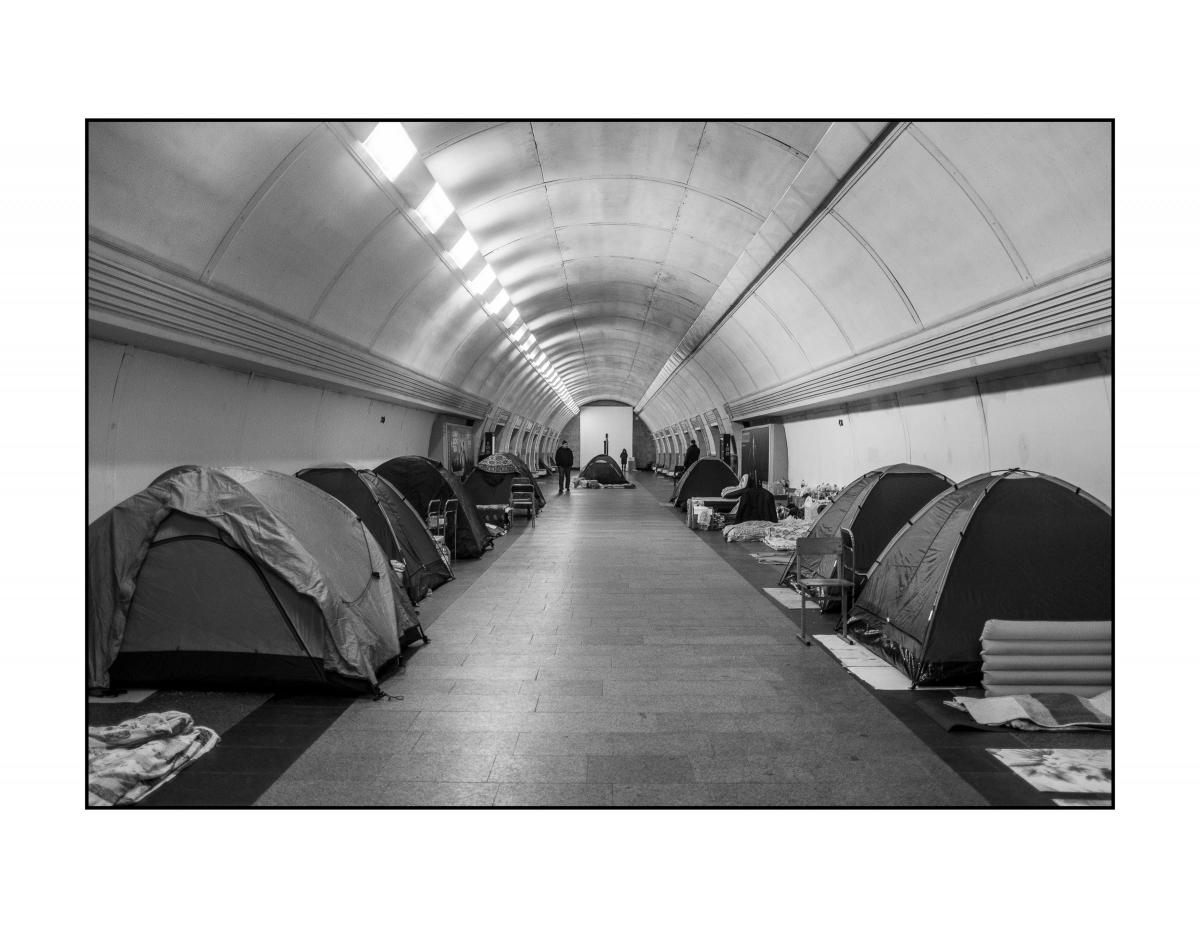

In the deep subterranean confines of the Kyiv metro, I found people who had sheltered there since the start of the war which is now over six weeks long.

Many had no homes to return to, having been destroyed by the random shelling and rocketing of residential districts. All these people in terms of international law could be designated as victims of war crimes.

In the northern Kyiv neighbourhood of Podil, I spoke with one man who was helping friends pack up their belongings before driving them out of Kyiv to a safer place. Even if they were to return as the threat against the capital recedes, the homes they left behind are uninhabitable ruins.

Which brings us to the question of accountability for such war crimes. Is it ever likely that those who gunned down civilians in the streets of Bucha, dumped corpses into wells with bags over their heads, tortured and raped, or unleashed barrages of shells on homes in Borodianka, Mariupol or Podil will ever be brought to justice?

There are several ways that countries and individuals can be made to answer for war crimes. The International Criminal Court (ICC), established in 2002 in The Hague, Netherlands, was set up to investigate and prosecute war crimes, genocide, crimes against humanity, and crimes of aggression. Its chief prosecutor, Karim Khan, took the unusual step of visiting western Ukraine briefly in March, where he held a video conference with President Zelensky. But neither the US, Russia nor Ukraine are party to the agreement that set up the ICC.

In addition to the ICC, however, the UN has in the past set up special tribunals to prosecute war crimes, as it did after the Balkan conflict in the 1990s. Any future war tribunal might, alongside atrocities carried out by invading Russian forces and their civilian leaders, also be expected to investigate reports of alleged crimes by Ukrainian soldiers during the war.

But all of this, should it ever eventually come about, is a long way off. While the immediate threat to Kyiv might have diminished for now, Russia’s promised intensification in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region has all eyes focused on how the war there will now play out.

More to surface

IF one thing is certain it’s that many more alleged war crimes are sure to surface in the bitter fight for this part of the country that Putin dearly wants to seize control of and Zelenskyy will be under pressure to defend at all costs.

While an array of international judicial institutions has jurisdiction over abuses that Putin’s military is accused of carrying out in Ukraine, those courts differ in how they work and how their rulings are enforced. Few, ultimately, have any leverage over Russia.

“The concern I have is that we fast-forward three years and there are half a dozen or so trials for mid-level commanders in The Hague for people who did things at Bucha, but the rest of the people like Putin and his military and defence leaders are unscathed,” observed Philippe Sands, director of the Centre for International Courts and Tribunals speaking to the Financial Times a few days ago. “That would be a deplorable outcome,” he added.

Deplorable, indeed, and of little consolation to those Ukrainians already the victims of crimes again humanity. Those like the women and children I saw last week at Warsaw railway station in Poland having earlier crossed the border from Ukraine that day.

Standing on the platform in the darkness and sub-zero temperatures amid snow flurries and a biting wind, I watched as an endless tide of grandmothers and mothers, their offspring in tow and struggling with baggage, stepped into what for many was an unknown city and future.

How terrifying must it be to leave everything behind including fathers, husbands and sons, and step into an unfamiliar city in the dead of night with nowhere to stay and unsure of what tomorrow will bring?

Every one of these people forcibly displaced is a victim of war crimes perpetrated by Russia. But don’t hold your breath waiting to see Vladimir Putin or any other top Kremlin officials in the dock at The Hague any time soon.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel