WE all have a children’s TV show we look back on fondly, and CBBC probably created your favourite programme. We watched them together at the same time in the afternoon as these TV series helped shape us into who we are today, and they aimed to help us make better sense of the world.

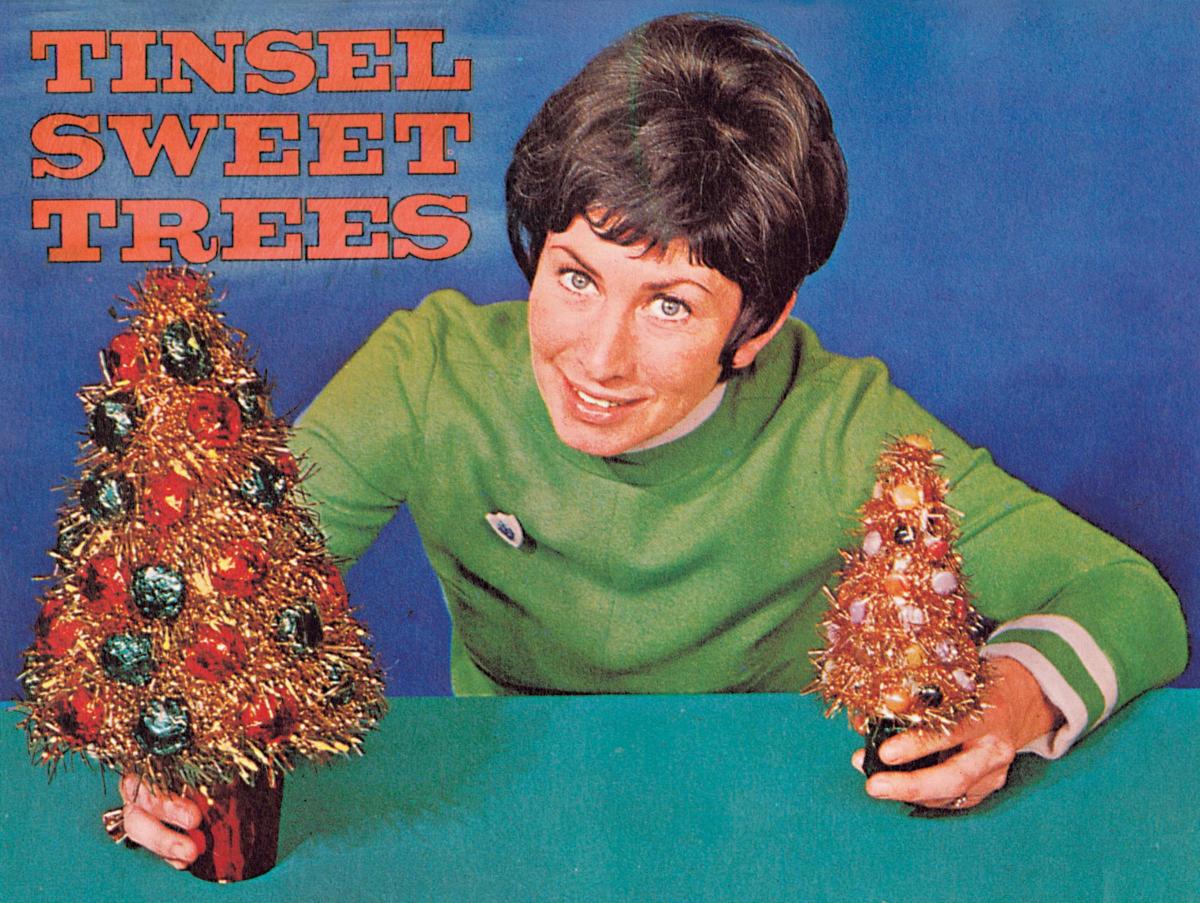

I tried (and failed) to create Blue Peter's tinsel hanger advent calendar. I learnt about the dangers of drug abuse via Zammo McGuire’s storyline on Grange Hill and was entertained by the chaos of live Saturday morning TV’s Going Live.

These are some of the CBBC series that helped me as a child keep informed, educated and entertained from my home in Merseyside. These TV series are why I now work in television and live in Scotland today – jumping at the chance to travel up the M6 to work for CBBC Scotland as a fresh-faced researcher producing four hours of live Saturday morning telly each week.

But I'm not looking back at the favourite children’s TV shows with rose-tinted glasses. The ever-changing multiplatform media landscape has resulted in seismic changes in the way children consume their media. OFCOM, the TV, radio and internet regulator, recently released a study that suggested only 4% of children aged three to 17 do nothing else whilst watching TV.

Multi-screening/multi-tasking when the TV is on is something children have instinctively done for years, whether it’s playing with toy figures and watching TV, or TV viewing alongside consuming content on a mobile or tablet device. Indeed, YouTube is the most-watched platform for children, with one in four watching no scheduled live TV.

Hence last week’s decision by the BBC to make CBBC, a 20-year-old linear channel dedicated to quality children’s TV programmes, into a “digital-only” online and BBC iPlayer service. On paper, this looks like a wise move. But there has to be an air of caution at the BBC when delving into all those statistics around children’s viewing habits.

The Corporation’s Director-General, Tim Davie, last week announced another round of cuts on top of an existing £1billion savings. Now the BBC need to make a further £500million annual savings due to the licence fee freeze by the Conservative Government. The Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, Nadine Dorries, has already criticised the BBC licence fee as “outdated” and should be replaced with a new “funding model" – although what a new funding model will look like is yet to be announced. The Secretary of State is reviewing the funding model of another public service broadcaster, Channel 4. The government is now arguing for the privatisation of the channel even though Channel 4 makes a profit at no cost to the taxpayer. The UK government has faced fierce opposition, with 96% opposing privatisation in a recent public consultation.

All this comes when we are so reliant on public service broadcasters in times of strife, especially when we turned to BBC services in our millions at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. It was a hideous time with children educated in isolation at home due to the various lockdown restrictions. An estimated 1.8million children did not have regular access to a laptop or tablet at the start of the first lockdown and could not receive education at home via online classes.

Memories of children huddled around one computer to learn in lockdown and governments hastily buying millions of laptops for schools are still fresh in our minds. At this time, the BBC rose to the challenge and took on educating the country via its online platform BBC Bitesize. When the second lockdown arrived, the Corporation quickly realised they needed to offer Bitesize programmes on BBC Two and the CBBC Channel because not all children can enjoy their important content online.

This leads to the question of how children from low socio-economic backgrounds will continue to access free, quality, public service children's television online if they don’t have the equipment to watch it? At least if a home has one TV, there is a good chance children can access CBBC programmes via a linear digital channel dedicated to their age group.

The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport has also challenged the BBC to employ 25% of its staff from low-socioeconomic backgrounds. CBBC first gave me, a St Helens lad, the dream I could work in television one day too. How on earth will the Corporation attract the next generation of TV producers, especially those from low socio-economic backgrounds, if they don’t identify with the output?

The decision to move CBBC from our TVs and to an online, non-linear, on-demand channel feels like a knee-jerk reaction to the rising might of Netflix, Disney+ and other subscription video on demand (SVOD). We should be reminded that the BBC’s output is unrivalled worldwide and is still a major attraction to international buyers. The BBC makes a quarter of its income from their commercial arm. An incredible £30million in 2020/21 from international sales and CBBC plays a significant factor in this too. Countries worldwide who do not invest in original children’s TV buy CBBC series because they can expect quality public service television.

In Britain, the BBC is experiencing a renaissance with younger viewers who value the quality and trustworthiness of BBC’s services. Another OFCOM report in November 2021, suggested in post-pandemic Britain, children and parents are now hugely appreciative of the BBC. Yet, the next issue facing families is the cost-of-living crisis.

Unquestionably a free to view children’s TV channel dedicated to quality programmes will be welcomed by families feeling the economic pinch. Many will inevitably cut back on the various SVOD and cable TV channel subscriptions as income becomes tight.

Ultimately, the decision to move CBBC to online-only will leave many viewers and their licence fee paying parents feeling shortchanged.

Daniel Twist is a BAFTA Scotland award-winning TV producer who has worked for CBBC in Glasgow and London. He is a lecturer for the Broadcast Production: TV and Radio degree at the University of the West of Scotland

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here