Today, on the anniversary of Napoleon’s defeat, one of Scotland’s most distinguished archeologists tells our Writer at Large the incredible true story of the Glaswegian who became the first civilian to discover the carnage on Waterloo’s battlefield

'The field was so much covered with blood, it appeared as if it had been flooded' (Thomas Ker)

AROUND 9pm, 208 years ago today, the guns of Waterloo fell silent. Up to 20,000 lay dead. A few hours later, in the panicked city of Brussels, a Scottish merchant called Thomas Ker packed a bag and travelled the short but perilous road to the blood-soaked battlefield.

Ker, forgotten to history until this very day, became the first civilian eyewitness to record the carnage that had unfolded just hours before his arrival. The horror Ker witnessed broke him. Today, he would be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. The battlefield was a tableau of dismembered body parts, dead and wounded soldiers, screaming, fear, mutilated men crying out for their mothers, mountains of killed and injured war horses; even the corpses of women, caught up in the cataclysm, littered the ground. Smoke and ruin was everywhere.

Glasgow University’s Professor Tony Pollard has rescued Ker for posterity. Wading through university archives, Pollard identified a bundle of Ker’s letters and a complete book he’d written about his experiences visiting Waterloo’s battlefield over and over again in the months after Napoleon’s defeat by the Duke of Wellington. In academic terms, the find was dynamite. Nobody had ever described the scene in the immediate aftermath of one of the most important conflicts in world history.

The Waterloo battlefield

Pollard is professor of conflict history and archeology, and director of the Scottish centre for war studies and conflict archeology. It’s a long title. For shorthand, it’s better to call him Scotland’s leading battlefield archaeologist, renowned for his work at Waterloo, and investigations into the Zulu Wars and the Falklands conflict.

The discovery of Ker’s documents is so significant that Pollard is publishing a paper on it which appears later today in the Journal of Conflict Archeology. With historic neatness, Waterloo took place on a Sunday - just like today - on June 18 1815. “Ker gives us the earliest civilian account written down of the scene of battle after it’s finished,” Pollard says. “It’s real gold.”

'I have also sent my description of the Battle of Waterloo, in all 139 pages … it has cost me trouble and some expenses to collect and compose it' (Letter from Ker, to his nephew John, in Glasgow)

Ker longed for his work to reach public attention. Sadly, he was to be thwarted. It seems attempts by his family to have his eyewitness account published came to nothing. Pollard suspects Ker simply wasn’t “posh enough” for the Regency period’s publishing industry.

Today, though, Ker finally makes his literary debut. The story of the discovery of Ker’s papers began when archivists, aware of Pollard’s work on Waterloo, alerted him to a bundle of old documents which had just been given to the university’s library by Ker’s surviving Scottish relatives.

“It became obvious to me very quickly that the material was of real importance,” Pollard says. Ker’s eyewitness accounts were “gems”. Ker may have arrived at Waterloo within hours of the battle ending. It makes Ker the equivalent of a modern-day war reporter who gets to the scene first. Ker didn’t know it, but in historical terms this was the scoop of scoops.

Professor Tony Pollard

Other civilian ‘eyewitnesses’ who wrote accounts of the battlefield didn’t arrive until long after the fighting ended. By then, the dead were cleared away, the ground picked clean by locals harvesting what they could from corpses, and the land was returning to normal, with farmers nearby ploughing again. Ker is the only civilian to see what the battlefield looked like as the smoke was literally clearing.

'Many is the tears they have cost me, to see their scattered brains and limbs on the gore field of battle, where I have been 18 times since that awful day … It is impossible to witness such a scene unmoved' (Thomas Ker)

It’s not just that Ker was the first civilian to record the events at Waterloo which makes his account so historically important, it’s also the fact he returned repeatedly over an extended period. It gives his reports not just authenticity but incredible detail. Other ‘eyewitnesses’, like Scotland’s Sir Walter Scott, weren’t really eyewitnesses at all, rather they arrived at least a month after the battle ended, often staying no more than a day.

The irony is that whilst Ker gives us so much information about one of the world’s most important battles, we know so little about him. He had family on Glasgow’s Broomielaw, and was a textile merchant in Brussels. He was clever and well read, quoting Laurence Stern’s ‘Tristram Shandy’ in letters home, probably the most avant-garde novel of the era. He clearly has aspirations to become a writer, “dabbling in doggrel poetry”. But that’s all we really know. Pollard, though, may soon dig into Ker’s life to discover more about him.

Brussels was only ten miles from Waterloo. “It’s possible to hear cannon fire in the city when the battle is raging,” Pollard explains. “On the day the battle was fought, there were panics in Brussels that the French had won and were on their way. Quite a lot of the civilian population - certainly quite a few British - remove themselves to places like Antwerp. Thomas didn’t.”

The battle began around 11am and raged until nightfall. Perhaps, some time around dawn the next day, Ker made his way to the scene, in an act of extraordinary courage.

Burning bodies at Hougoumont by James Rouse.

'Here were the fields covered with fragments of what those victims and brave men wore, or carried when they fell … Legs and Arms some with broken swords still held fast in the hand, heads here, and body’s there … muskets, sabres, pistols…the plaids and plumes of Scotland … Much more might be described by which the reader might be more shock’d than entertained' (Thomas Ker)

One of Pollard’s most important academic projects is ‘Waterloo Uncovered’: the archeological excavation of the battlefield. Military veterans take part as a form of recovery therapy for trauma. Ker’s long-lost account has brought to life the evidence of the past which the Waterloo Uncovered team has dug from the earth.

Excavations at Wellington’s Waterloo field hospital revealed the horror of conflict in the early 1800s. “We found a burial trench, filled with amputated legs,” Pollard says. With grim historic irony, around 20 surgeons from Glasgow University served at Waterloo. At this one field hospital site, “at least 500 limbs were removed on the day. It gives you an idea how brutal it was”.

Musket-shot was one ounce lead weight. “When it hits you, it breaks into pieces causing dreadful wounds,” Pollard explains. Most amputations were probably due to gunshot shattering limbs on impact. “There’s really no such thing as flesh wounds at Waterloo,” Pollard adds. “And of course, limbs are removed with saws, without anaesthetic, without antibiotics.”

Often if shock or loss of blood didn’t kill injured soldiers, they died from gangrene in infect wounds. Pollard says Ker’s account gives “the real visceral impression” of what the battlefield looked like when the butchery stopped.

'On arriving at Waterloo, the Church was full of wounded, and also many houses, of the troops of different nations, and death hard at work amongst them. But few of the native inhabitants was as yet returned to their homes. I got some water (which was not easily obtained) to give to some of them to drink, and several of them died in my arms while holding them up' (Thomas Ker)

Ker was no callous ‘tourist’, Pollard notes. It was a mix of almost journalistic curiosity and the simple humanitarian urge to assist the wounded which appears to have motivated him. “He seems to be there to see what he can do to help,” Pollard adds. “Several wounded soldiers die in his arms as he’s giving them water. He may have saved lives by administering water.”

The fact that the wounded were still dying on the field attests to just how early Ker got to Waterloo. “Once he got there, he’s not prepared for the horror that awaits him. It’s total carnage. He describes the field littered with thousands of dead, dying and wounded. He talks about scenes of gore, with limbs lying around and dismembered corpses. He’s there as the wounded are being brought off the field. He mentions the buildings in nearby villages packed with wounded soldiers.”

'I cannot but faintly attempt to give a description of the scene of slaughter which the fields presented, or what any person possessed of the least spark of humanity must have felt, while he viewed the dreadful situation. No-one who has not seen it can imagine how touching it was to see the dying, the wounded, and the dead, of the thousands around you, and all that were able to articulate calling for water to drink, and but little or none to be had for them. Allies and French were dying by the side of each other. The cries of all now demanded the compassion of the bystander without exception' (Thomas Ker)

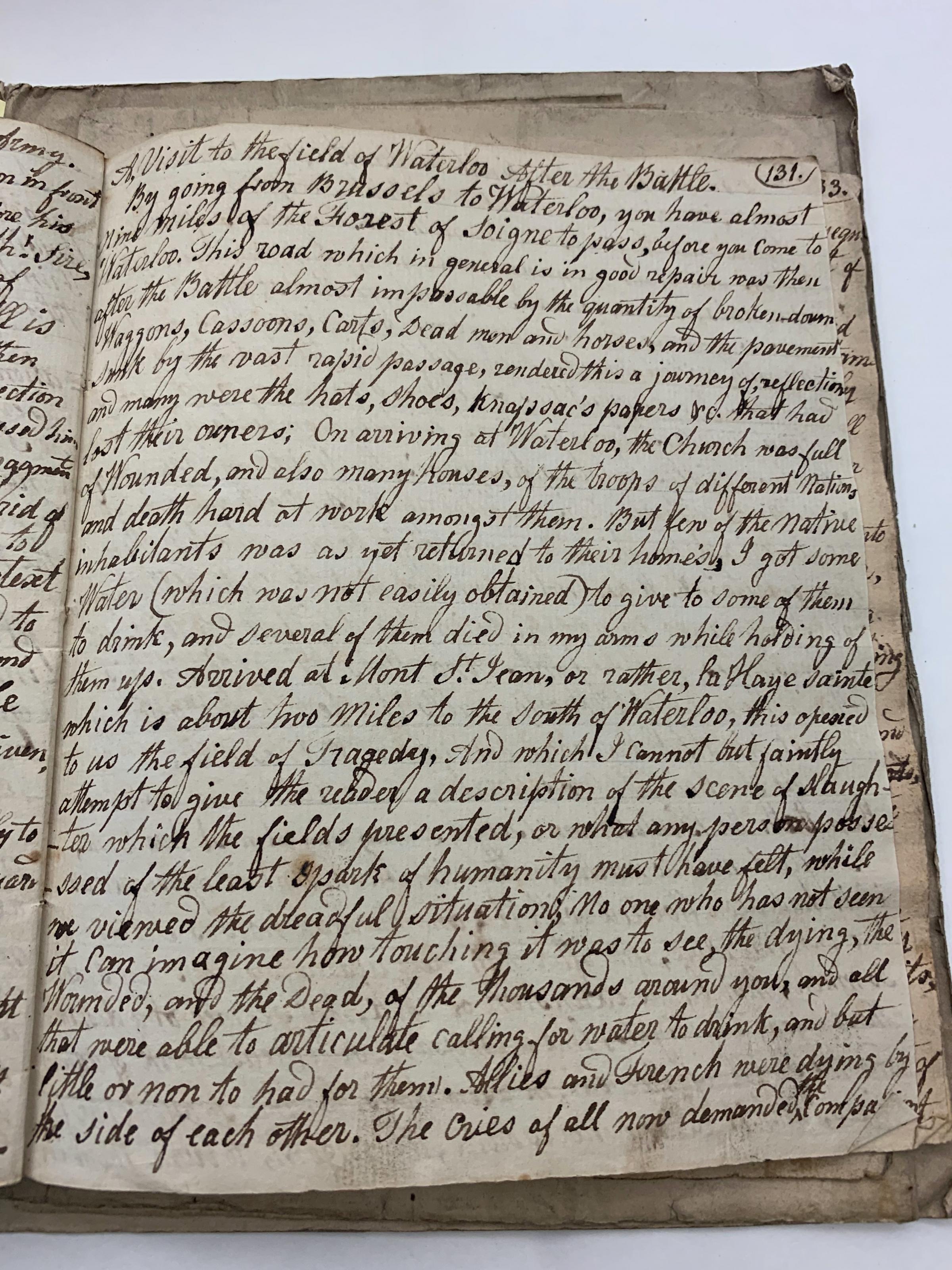

Ker Sample Page, Glasgow university Library Special Collections.

“I think he unknowingly traumatised himself on that first visit,” says Pollard. Pollard well understands the trauma of conflict. He’s taken veterans, from wars like the Falklands, to the site of battles they fought in order to help them come to terms with PTSD. It’s a form of ‘immersion therapy’, Pollard adds. Ker’s repeated visits to the battlefield over a long period of time may have been an unconscious attempt to “enact the same sort of therapy”.

By watching the battlefield incrementally cleared of bodies, by seeing the wounded recover, by watching “the land heal”, Ker may have found some solace to the trauma he experienced on his early visits.

Ker may also have benefited from befriending survivors, including a “Captain MacDonald of the 92nd Highlanders” who was wounded at Waterloo. In 1816, Ker writes to his brother saying of MacDonald: “If he goes to Glasgow he will call on you.”

By going from Brussels, you have almost nine miles of Forest of Soigne to pass, before you come to Waterloo. This road … [is] almost impassible by the quantity of broken down wagons, dead men and horses (Thomas Ker)

One of the reasons why Ker was first on the scene is that the journey to Waterloo after the battle was highly dangerous. Few had his bravery to risk the trip. Many Prussian troops, who fought alongside British soldiers, had deserted and turned to highway robbery. The forest of Soigné on the road to Waterloo became a zone of anarchy, rape, robbery and murder. So Ker knew he was taking his life in his hands when he set off.

Many other eyewitnesses waited a long time to make the journey. One of the most famous accounts came from the wealthy writer Charlotte Anne Eaton. She was perhaps the original ‘war tourist’, arriving in Brussels ahead of the battle as she knew history was about to be made. Yet it wasn’t until a month after fighting ended that she traveled the few miles to Waterloo. “She puts off going because she’s told the forest is a very dangerous place,” Pollard explains.

When published eyewitnesses like Eaton make it to Waterloo, the carnage has been cleared away. These other writers usually visited only once. Eaton stayed on the battlefield “just a few hours”. Yet we can still see why her account is described as ‘battlefield gothic’. She refers to “shallow graves with arms sticking out”. Pollard, who has great respect for Eaton as a woman in the 1800s entering this ‘male world’, adds: “The point is, what she saw was incredibly sanitised, horrific as it was, compared to what Ker saw.”

Waterloo effectively began what we would now call ‘Dark Tourism’ with wealthy British visitors arriving to buy souvenirs in the battle’s aftermath. Ker, as the first civilian eye-witness, picks up many treasures. He talks of one Edinburgh man “who took part of a skull … off the field of battle”.

Ker's collection of battlefield artefacts included “a tartan coat that [Colonel] Miller fought in that day”, adding: “It is bloody.” He also sends home a cuirass - the breastplate worn by elite Napoleonic troops. Ker says it is “all over blood … it stunk for a month … I hope you will never part with it”. He asks his nephew to keep it “in our family as a memento”.

Ker possibly bought the cuirass from some local entrepreneurs who had effectively turned themselves into canny souvenir vendors. In the years after Waterloo, the nascent tourist industry degenerated grotesquely. There’s records of a group of young drunken Britons “basically on a Club 18-30 excursion”, Pollard says, some years after the battle who “get pissed, harass the local girls - a very familiar picture today in places like Prague with stag nights - and take home the hand of a soldier”. Waterloo eventually became, he says, “the equivalent of people taking selfies at Auschwitz today”.

Factories in Birmingham and Leige begin making fake souvenirs, like buttons, claiming they came from fallen soldiers.

'On Monday the 19th June the bodies of the dead men and horses lay mangled and thick all over the field, also many women fell the victims of that day, who by their imprudence advanced too near the front of the line to be near their husbands. All afforded a view that was shocking to behold, and impossible to describe': Thomas Ker

One of the most historically fascinating, and painfully forgotten, aspects of Ker’s account is the number of dead women on the field. Many were ‘camp followers’: soldiers’ wives, cooks, servants, and also sex workers, in the train of the army. Other dead women, some from the local civilian population, “came to loot the bodies”, and were shot.

At least one woman was found among the dead dressed as a French cavalry officer. Her true identity was discovered when her body was stripped.

Around 8000 horses were killed during the battle. One Scottish officer at Waterloo spoke of seeing a horse standing on three legs on the field after one of its limbs was blown away. Pollard’s Waterloo excavations revealed skeletons of euthanised horses, shot in the head, buried near a British field hospital.

Napoleon

'On the Sunday after the battle, I went into [a] farm where I found the farmer, his wife, and a woman servant, who had only returned that morning to their shattered home, it was with hard labour they were at, washing and scraping the blood off the floors, which was hard and more than an inch deep. The house was surrounded with dead horses, and the smell in every part extremely offensive and the field all covered with men at work, burning and burying the dead, and women and children gathering the spoils from the battle' (Thomas Ker)

Other famous ‘eyewitness’ accounts of the aftermath of Waterloo carry none of the historic weight of Ker’s writing. Sir Walter Scott came to compose a poem but didn’t arrive until August, two months after the battle was over, and the poet laureate Robert Southey didn’t arrive until October. Scott’s account is also somewhat suspect. He talks, says Pollard, of “victorious Highlanders cooking steaks using [French cuirasses] as frying pans. Obviously he wasn’t there to witness that. I think he made it up”.

Unlike Southey, Scott or Charlotte Eaton, Ker didn’t have the social cachet the Regency publishing industry required. He lacked their “privileged background,” Pollard says. “All the others have reputations as writers and artists. This was Joe Blow from Glasgow. He doesn’t have any of their advantages. There may be a class thing there.”

Nor was Ker some ‘war-junkie’. He explicitly talks about “the horror of war”, says Pollard, “widows and orphans”, and the suffering of the “civilian population”. He never boasts about his visits, as other writers did. Nor does he indulge in jingoism over Britain’s victory. “His take is that this is a horror-show.”

Ker’s letters home to Glasgow continue until 1820, and then he just “disappears from history”. Pollard adds: “He was no spring chicken at the time of the battle.” Although, it’s hard to pin down his age, Pollard thinks Ker was around 56 in 1815.

Pollard is delighted to help Ker finally fulfil his wish of having his account of Waterloo published. It’s like “reaching back and shaking hands with the past”. But the discovery has set his mind racing. What else might be out there he wonders? “There could be other accounts mouldering in attics and trunks somewhere,” he says. “Please, if anybody has that sort of thing then come forward.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel