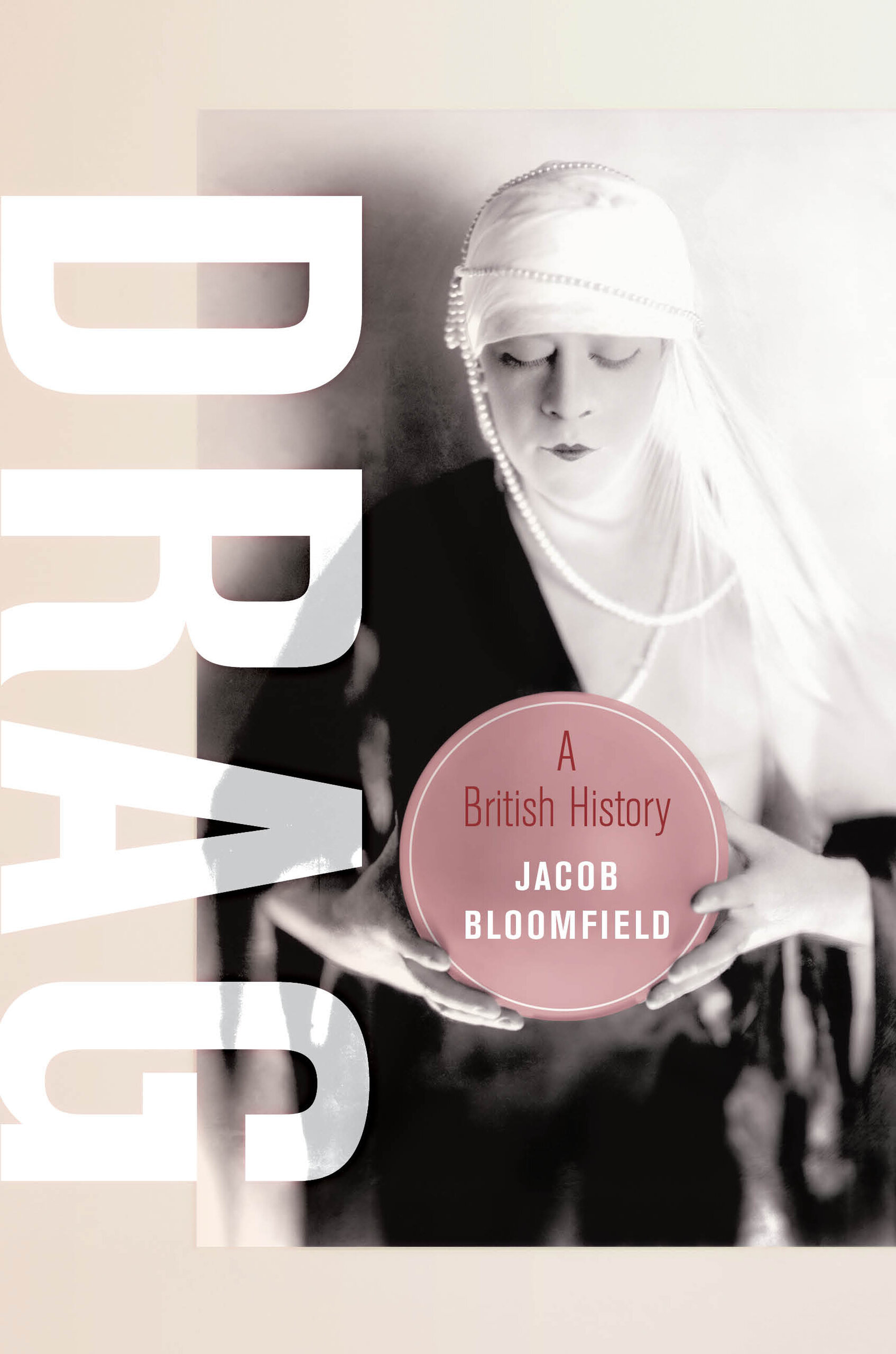

Dr Jacob Bloomfield is one of the world’s leading experts on drag – he even learned the ropes as a drag star on the Scottish circuit. Here, he talks to our Writer at Large about his research uncovering the truth about drag and why it’s a new front in the Culture Wars

Dr Jacob Bloomfield is an expert on the history of drag in the UK

What better way to study your specialist subject than to live it? Dr Jacob Bloomfield is the uncontested expert when it comes to the history of drag in this country.

Though some people might know him better as Cupcake, an acclaimed Edinburgh drag star.

Bloomfield, a respected cultural historian educated at Edinburgh University and now an academic in Germany, has just dropped slap-bang into the middle of Scotland’s culture wars.

Drag has found itself embroiled in the bitter row over trans rights, with events like Drag Queen Story Hour for children picketed and protested. Bloomfield’s new book Drag: A British History seeks to put intellectual rigour into a debate typified by social media hysteria. After all, how can you critique something if you don’t understand it?

Sitting down to talk with The Herald on Sunday, Bloomfield explains that fittingly, for the season, there would be no such thing as drag without that great British tradition: the Christmas panto.

Panto

It was standard practice in Victorian music halls for nearly “every male comedian to have a woman’s part in his repertoire”. This was central to the life of an “all-round entertainer”.

The biggest stars of the day like Dan Leno dragged up, often as panto dames. Major British celebrities of the early-20th century like Arthur Lucan, who played elderly women on screen, followed in Leno’s footsteps, taking the spirit of the panto dame into cinema.

Their sexuality was never questioned. Both Leno and Lucan were straight “as far as we know”, says Bloomfield. Other stars like Billie Manders in the 1920s dragged up as glamorous women. “He had a wife,” says Bloomfield, “so I assume he was straight too.”

For Victorians, panto was simply entertainment. It wasn’t seen as sexual, despite the cross-dressing. Pantomime emerged from a mix of earlier theatrical genres like Harlequinade, Burlesque and the Extravaganza, which often saw men dress as women, and “satirised contemporary politics and culture under the auspices of fairy tales”.

By the late-19th century, Harlequinade, Burlesque and Extravaganza, “combined to become pantomime”. Leno “elevated the dame to pantomime’s main character”.

The panto dame often “spoke to working-class concerns”. Think of Widow Twankey, the dame in Aladdin: a poor, put-upon washerwoman. The famous 1890s play Charley’s Aunt – still performed today – played with the panto dame role for middle-class tastes.

Bloomfield finds the notion that panto is inherently “children’s entertainment a little weird. A lot of the jokes, from the start, have been quite racy”. He points to the Principal Boy, played by cross-dressing women. It’s a role, he says, “deliberately meant to be subjected to the male gaze”. The Principal Boy is often performed by young, beautiful women in “skimpy clothes. It’s a way to ogle women”.

He references one newspaper review from the 1950s where the writer “discussed the measurements of the Principal Boy – like such and such bust, such and such waist”, adding: “There’s cognitive dissonance between this and saying ‘oh, it’s totally for kids’.”

Not everyone, though, was comfortable with the concept of the Principal Boy. Famously, Queen Mary – George V’s wife – once covered her face with her programme when she saw a cross-dressing woman on stage.

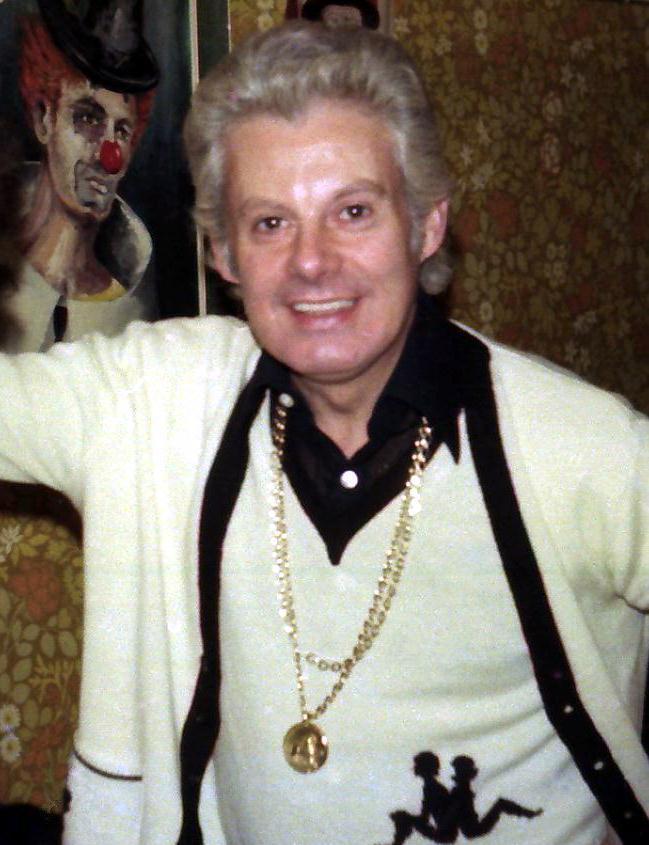

Danny La Rue was one of Britain’s biggest celebrities of the 1970s

Music halls

HOWEVER, the origins of drag go back much further than panto. Ancient Greek drama saw men playing women. The same was true in Shakespeare’s time. But drag really took off in the 1870s. “That’s when our modern conception of drag starts,” Bloomfield explains. The 1870s is also the first time the word “drag” is used in newspapers to describe men dressing as glamorous women on stage.

Ernest Boulton and Frederick Park – known as Fanny and Stella – were the most renowned drag artists of this era. They were a big hit in Victorian theatres, and even invited to perform privately in wealthy patrons’ homes. Both were middle-class and gay, and eventually targeted by police. They were tried for “conspiracy to commit sodomy” but found not guilty in a sensational trial.

Both continued to perform after the case.

Police animosity to Boulton and Park was probably influenced by memories of raids on so-called “Molly Houses” in the late 1700s where, as Bloomfield explains, “men who dressed as women would get together and have parties and sex with each other”. It was all part of Britain’s “demi-monde”.

Ironically, given how heated the national conversation is today around trans rights, Scotland became something of a bolthole for young cross-dressing men in Victorian times who fell foul of the law. In his book Fanny And Stella, the journalist Neil McKenna explains how a quick dash over the Border in a suit and tie was often enough to throw London’s vice squad off the trail.

However, most Victorian drag acts weren’t controversial. By the end of the 19th century, music halls, where drag acts appeared, were “becoming more family-orientated”, says Bloomfield.

Essentially, there has always been effectively two types of drag artist: those who use drag as “a means to express their gender nonconformity or same-sex desire”, and those who dress as women to entertain, and may or may not have been “straight”.

Boulton and Park fall into the former category and Dan Leno the latter. And it’s the former who enrage “social conservatives”.

“Drag doesn’t mean one thing for either practitioners or observers,” says Bloomfield. “Nobody looks at paintings and thinks ‘oh, only one type of person paints, for only one kind of audience’. So while the connection between drag and queer culture shouldn’t be dismissed, drag has myriad other meanings.”

Around the same time that Boulton and Park and Dan Leno were wowing their respective audiences, “cross-dressing starts to become pathologised by medical experts”, says Bloomfield.

This led to some seeing drag as a sign of mental disturbance. Yet, to most Victorians drag was just “light entertainment. They considered it a night of fun”.

However, for some, these seemingly innocent song-and-dance routines by men in drag held a sexual frisson. Bloomfield has explored letters written by Victorians where seemingly ‘straight’ men discussed their fantasies about drag performers.

So, back in the 1800s, people were seeing what they wanted to see in drag. For some it was a laugh, to others it was titillating, many didn’t care, and a section saw it as morally offensive. The same is pretty much true today.

Soldiers

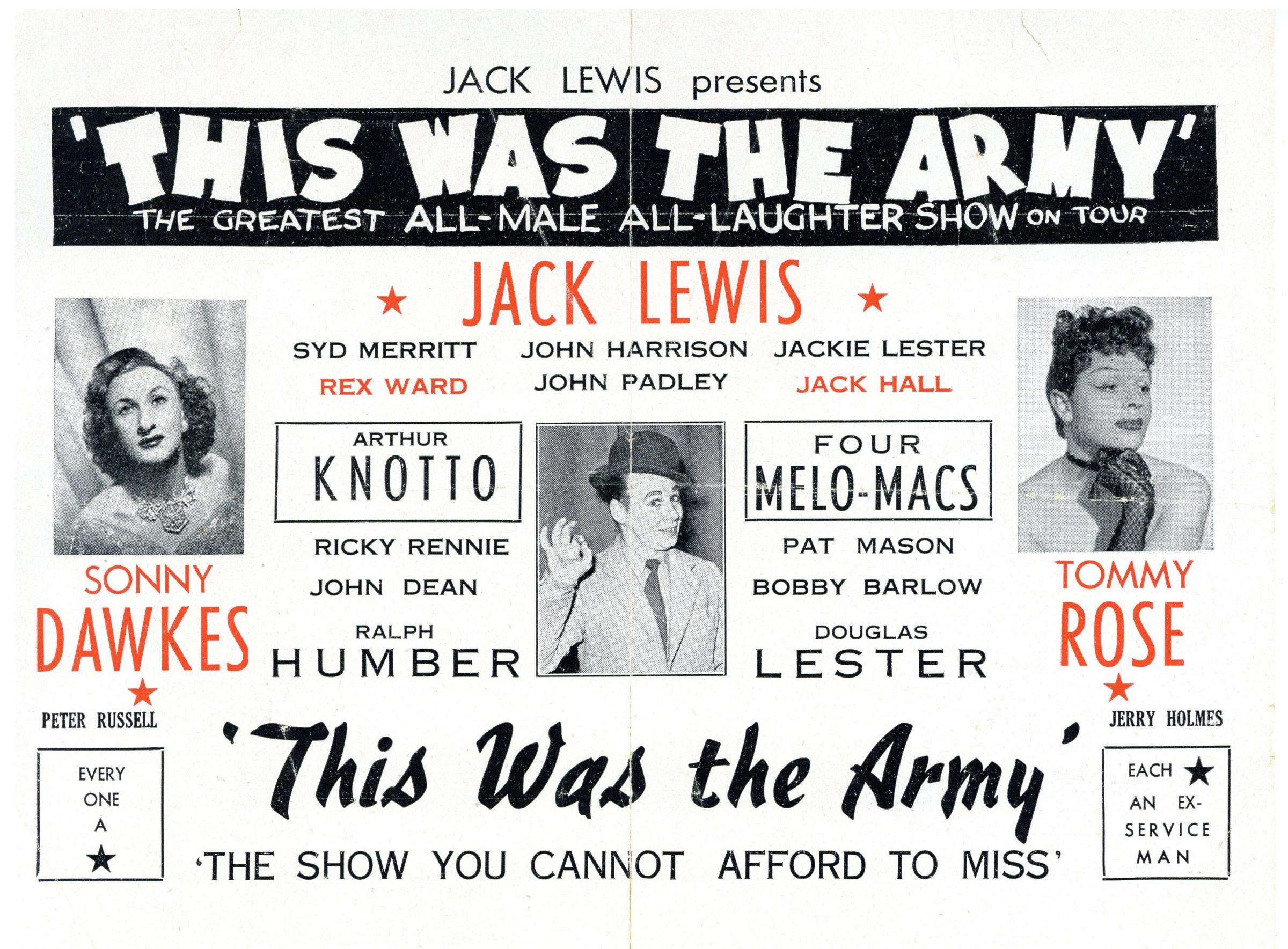

DRAG underwent a metamorphosis after the First World War with a boom in ex-servicemen’s drag troupes. The most famous was Les Rouges et Noirs. These veterans of the trenches were “among the most celebrated performers of their day”, Bloomfield explains, and appeared in one of Britain’s first talking movies.

Bloomfield notes that many newspaper critics who were “presumably, or ostensibly, heterosexual men would go into gushing detail about how sexy they thought the performers of Les Rouges et Noirs were. This wasn’t seen as a crisis of sexuality, it was part of the draw of the show”.

Drag throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, says Bloomfield, was seen as “much less a bête noire” than today. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office, for instance, which had the power of censorship, was very lenient with drag, compared to other performances deemed overtly sexual. “To what extent was drag controversial or a target in a culture war? It wasn’t really,” says Bloomfield.

The drag show “We’re No Ladies” was subject to complaints but the Lord Chamberlain said “we can’t ban a show merely for having female impersonators”. Bloomfield adds: “Some people did associate drag with homosexuality, but that idea wasn’t widespread. Not everyone watched a drag show and thought ‘this is gay’ … Most people saw a drag show and didn’t think about it afterwards. It was just entertainment, and that’s what was happening throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.”

One now-forgotten drag act was Arthur Lucan’s famous character Old Mother Riley, who was a huge hit in British cinemas during the 1930s and 40s. Old Mother Riley proves, says Bloomfield, the importance of academics studying what’s often dismissed as mere pop culture ephemera. Lucan’s character was actually rather revolutionary: an Irish washerwoman who railed against Britain’s ruling class in films like Old Mother Riley MP.

Army drag

Nazis

MEANWHILE, in Germany, Weimar-era freedoms, where men could get an official pass to “cross-dress”, were targeted by Nazis. Magnus Hirschfeld who ran Berlin’s Institute of Sexology fell victim to one of the first book burnings. Hirschfeld advocated for what we would now call LGBT rights.

After the Second World War, the obsession with ex-servicemen’s drag troupes continued unabated. Think of the old TV sitcom It Ain’t Half Hot Mum, set around an army concert party with cross-dressing characters.

These troupes didn’t just perform “glamour drag”, but also routines featuring “all sorts of representations of femininity, including mother figures”, a sign of men at the front missing their families.

Critics talked of “their admiration for the wartime service” of these drag artists. However, it was the quality of the performances which made the ex-servicemen’s troupes a hit, not their battlefield bravery.

There were dozens of army drag troupes, with names like Soldiers In Skirts and We Were In The Forces. One reviewer, Bloomfield explained, said of an army drag act: “Even if the show wasn’t good, we’d still feel inclined to praise it as we want to support our Tommies, but we didn’t have to pretend as it was a genuinely great show.”

Edinburgh

SCOTLAND is central to the cultural history of army drag. Bloomfield says that although ex-servicemen’s drag acts were common they didn’t leave much of a “cultural imprint”, so there’s little to remember them apart from some posters and newspaper reports.

But the long-forgotten novel Chorus Of Witches, written under the pseudonym Paul Buckland in 1959, tells the story of an ex-army drag troupe in Edinburgh.

“It’s one of the most important historical documents regarding ex-servicemen’s drag revues,” Bloomfield says. It’s another irony, given the furore around trans rights and drag acts that has taken place in Scotland over recent years.

Comedians like Dick Emery were inheritors of ex-servicemen’s drag acts. Bloomfield points out that some of those protesting Drag Queen Story Hour – where drag artists read books to children – would have watched Dick Emery on TV in the 1970s and 80s and loved his show, even though he routinely dressed up as women and performed routines which were smutty for the time.

Bloomfield notes that some who oppose drag will say that performers like Danny La Rue – a drag star who was one of Britain’s biggest celebrities of the 1970s – “was fine because he wasn’t shaking his penis in front of children”.

Bloomfield makes clear that Drag Queen Story Hour isn’t sexual, it’s simply drag performers reading books. But he adds that it’s forgotten that “La Rue performed raunchy panto for children.”

At one point La Rue – who in later life was open about being gay – had a drag club in Mayfair, and another drag performer called Ricky Renee had a club in Covent Garden. La Rue was a regular on prime-time TV. So by the 1970s, drag “was culturally ubiquitous”. And there was little or no outcry.

Conservatives

Bloomfield, however, says La Rue’s drag was basically “conservative”. He didn’t challenge society in any way, and was definitely not an alternative comedian. In fact, some stars who played with drag were adored by the Conservative Party. Kenny Everett, Bloomfield points out, dressed up regularly as women – in overtly sexualised performances – and took to the stage at the Young Conservatives conference in 1983 shouting “Let’s bomb Russia”.

By the 1980s, drag was part and parcel of youth culture thanks to the films of John Waters featuring drag stars like Divine. Come the 1990s, drag was a TV mainstay with the rise of Ru Paul. By the 2010s, RuPaul was a global superstar and drag was described as having its “big cultural moment”.

And, of course, one of Britain’s most beloved performers for decades was a drag star: Barry Humphries aka Dame Edna.

Bloomfield, however, adds that since the 1870s “people have been saying ‘drag is having a moment’ pretty much every decade”. The same was said of Danny La Rue and drag in the 1970s as was said of RuPaul in recent years. “From the 19th century, drag performers weren’t only popular, but some of the most popular performers of their day.” Drag has never been “outsider art”.

As an art form, drag became easily exportable between Western countries due to what Bloomfield calls the “homogenisation of feminine glamour”. Hollywood “pushed” a Western vision of how women looked and drag artists were able to use that whether they were performing in New York, London, Paris or Munich.

Dr Bloomfield's new book

Sexuality

Bloomfield turns to the issue of why drag has been embroiled in recent culture wars. “Social conservatives,” he says, “are always looking for targets. They’re always going to be against sexual modernity and social progressivism, and they’ll be looking for things which represent that.

“So when you hear social conservatives decry drag, part of it is their dislike of drag, but a big part is to them that drag now represents the LGBTQ movement more widely and social progressivism.

“When social conservatives see Pride flags, it might raise feelings of homophobia, but they also see it as a symbol of progressivism and sexual modernity. When you ask them ‘why do you dislike Drag Queen Story Hour?’, they’ll say it’s men exposing kids to sexuality, so they’re essentialising drag as a sexually-loaded performance.

“My argument is that drag is an art form like any other. There’s drag that involves overt displays of sexuality but there’s also wholesome drag and I consider drag artists reading books to children to be wholesome.

“But these social conservatives essentialise drag as perverse. They put it in the same category as strip shows.”

He adds: “Social conservatives glom onto a few issues every generation.” In Victorian times, it was masturbation. For Britain’s Mary Whitehouse and America’s Moral Majority in the 1970s and 80s, it was pornography. Today, along with abortion, it’s trans rights and drag.

For social conservatives drag is a “symbol of moral decay”, Bloomfield says. “In the 1960s, these people might have been decrying the pill or rock music. Drag is just what they’ve now targeted as their enemy in the culture war, in their war against social liberalism.”

Bloomfield defines Drag Queen Story Hour like this: “Remember George W Bush reading My Pet Goat to kids on 9-11?”

The ex-president was famously filmed reading nursery stories to children as the September 11 attacks happened. “Well, imagine if Bush was wearing a bouffant wig and eyeshadow – that’s Drag Queen Story Hour.

“It’s benign. Honestly, I’d be more worried about Bush reading to children. Social conservatives go into flights of fancy about men waving their d***s at children.

“In some ways, though, if you’re a fan of drag you might even see Drag Queen Story Hour as a bit of a threat as the argument could be made that it’s making drag too genteel.”

Politics

IT was only when the “gay liberation movement got going”, says Bloomfield, that drag became “overtly claimed as a gay art form”. Drag also took on a political edge, with drag queens part of the famous 1969 New York Stonewall riots against police brutality towards the gay community.

This percolated through into popular culture with rock stars like David Bowie and Mark Bolan “presenting themselves in drag-adjacent modes”. Mick Jagger famously dressed in a frock at a Hyde Park concert in 1969. Today, Harry Styles continues that “gender-bending” style, Bloomfield adds.

Suffice to say social conservatives in 1970s weren’t impressed. The likes of Mary Whitehouse started to “push back against the permissive society. These are the exact same people who are protesting today”.

Bloomfield adds: “We think we’ve turned a page and gotten rid of them but they’re always around. They maybe change their language and tactics, but they’re basically the same ilk.”

Bloomfield isn’t blind to faults in drag though. It’s been accused of insulting women and he says: “Definitely drag can be sexist or racist – again, that’s because it’s an art form like any other. Rock music can be subversive and used for progressive ends, but rock music isn’t essentially progressive.

“Similarly with drag. Drag has great progressive potential but it can also be reactionary. To those who say drag is essentially sexist, I’d say ‘drag isn’t essentially anything’. I don’t think any art form is essentially one ‘thing’. Danny La Rue is an example of ‘conservative’ drag, but that’s not to say drag can’t be progressive.”

Despite the backlash, Bloomfield is certain drag will always be around. Drag shape-shifts to match the times. When radio started it was a hit on the airwaves and when film started, drag became big in cinemas. Today, it’s all over TV.

“Not only has drag persisted,” Bloomfield says, “but it’s persisted as a popular and critically-acclaimed form of entertainment. Drag will stick around. It will adapt and continue to flourish, no matter what the detractors do.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here