Two years ago this weekend Russian airborne troops landed at Hostomel airport and while the outcome of the ensuing battle helped scuttled the Kremlin’s attempt to take over the country Ukraine's position today remains a perilous one reports Foreign Editor David Pratt from Kyiv

The tell-tale signs of that fateful day are still visible everywhere. There are the walls of gigantic hangers pockmarked with bullet and shell holes still sooty black from the fires that engulfed them following explosions.

Not far from a deserted control tower and adjacent to the runway lie the now rusting carapaces of Russian armoured vehicles piled one on top of the other.

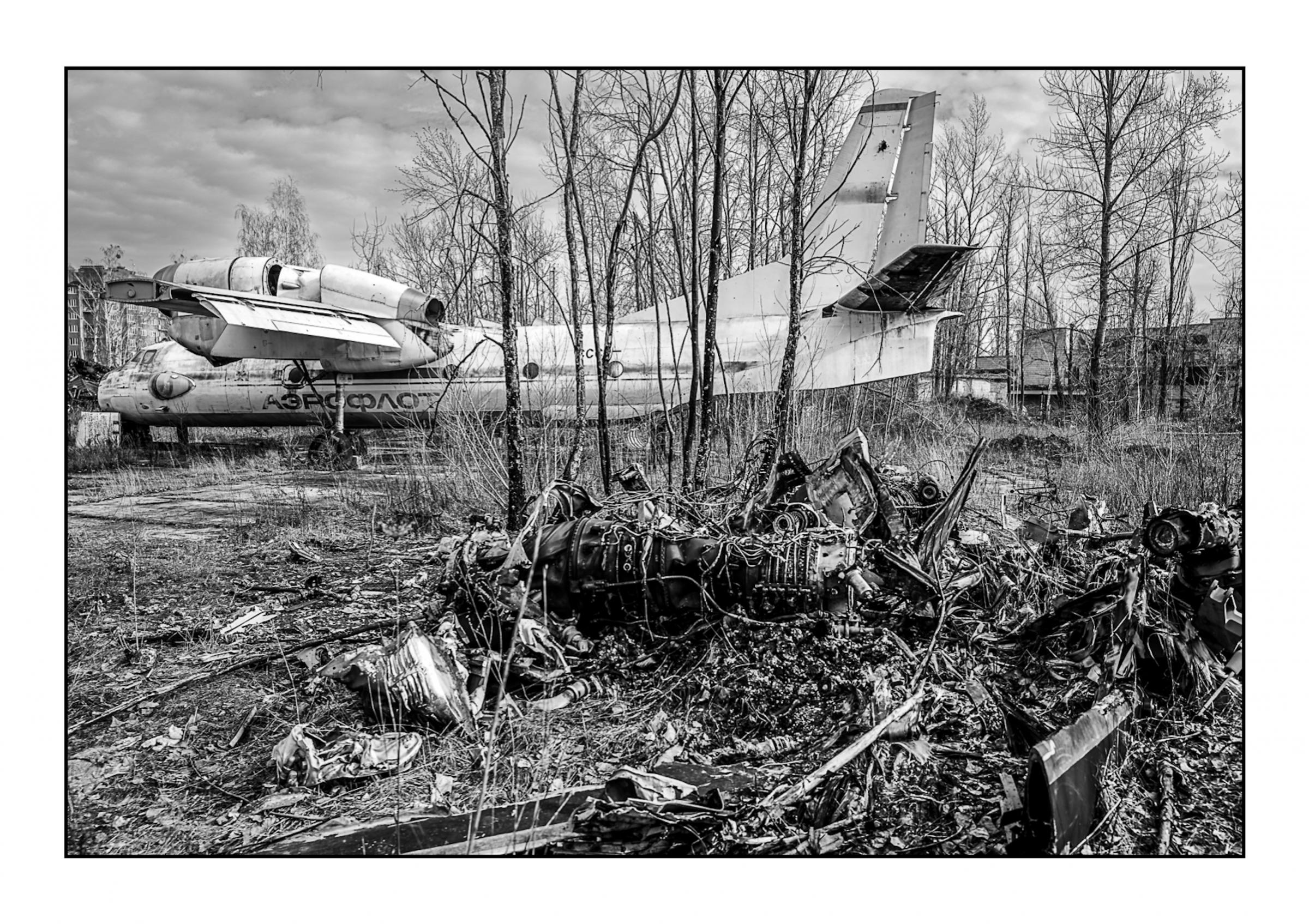

A Soviet era Aeroflot twin engine propeller aircraft sits among the overgrown grass its tail flap blowing forlornly in the wind with an eerie creaking sound, and the scattered wreckage of a Russian military helicopter serves as a macabre reminder of the invading airborne assault troops that were ferried into battle that day.

It was February 24, 2022, exactly two years ago this weekend, that Russia’s high-risk high-reward strategy to take Hostomel airfield, sometimes known as Antonov Airport, got underway, marking the first decisive battle of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and unleashing the biggest conflict in Europe since the Second World War.

That afternoon around 3:30 pm Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy would declare that “the enemy have been blocked, and Ukrainian troops have received an order to destroy them.”

But in fact the battle for the town of Hostomel town itself along with other satellite towns and villages like Irpin, Bucha and Moschun would ebb and flow for some time after that.

Hanger with destroyed Antonov at Hostomel airfield. Picture: David Pratt

Surprise attack

In what is known in military parlance as a coup de main, or surprise attack, Russia’s primary objective was to take control of Hostomel creating an airbridge from which it would launch an attack on Ukraine’s capital Kyiv that sits just 12 miles from the capital's centre, forcing Zelenskyy to flee or be killed by Russian special forces assigned with precisely that task.

To that end and prior to the invasion, Russian intelligence had moved infiltrators into both Kyiv and its surrounding satellite towns and villages including Irpin and Bucha.

It was still dark on the morning of 24 February when Ukrainian Interior Minister Denis Monastyrsky woke to the ringing of his mobile phone. On the line was Ukraine’s border guard chief, telling him his units were battling Russians across three of the country’s north-eastern regions. Monastyrsky hung up and dialled Zelenskyy.

“It has started,” Monastyrsky told the Ukrainian leader.

“What exactly?” Zelenskyy asked.

“Judging by the fact that there are attacks underway at different places all at once, this is it,” he said, telling Zelenskyy that it looked like a full-scale invasion bearing down on Kyiv. At Hostomel airfield with its 11,483 long runway capable of supporting the largest transport aircraft, Russia’s assault force of 30 or more helicopters and between 200-300 hundred soldiers from the 31st Guards Air Assault Brigade and 45 Separate Guards Spetsnaz Brigade was already battling the Ukrainian National Guards 4th Rapid Reaction Force located to the southeast of the runways.

A few days ago as I walked around the apron of the airfield among the detritus of that battle, it’s not hard to imagine the ferocity of the fighting. In what remains one of two gigantic hangers , the burned-out shell of an Antonov An-225 Mriya, the word largest aircraft sits like some gigantic beached metallic whale, its undercarriage tyres blackened and charred, and its fuselage ripped open to expose its giant interior once capable of carrying an enormous payload. But it would be the terrible human cost in the battle for Hostomel and surrounding towns and villages like Bucha and Moschun in the following weeks and months that would wake the world up to the horrors that have now unfolded across Ukraine for two long bloody years now.

After leaving Hostomel, I headed to the neighbouring village of Moschun, which I have visited on several occasions since the start of the Russian invasion.

With over 80 per cent of its buildings destroyed, Moschun today still has the feel of a ghost town even if some 1,000 or so of its residents have returned and there is a sense of repair and rebuilding underway.

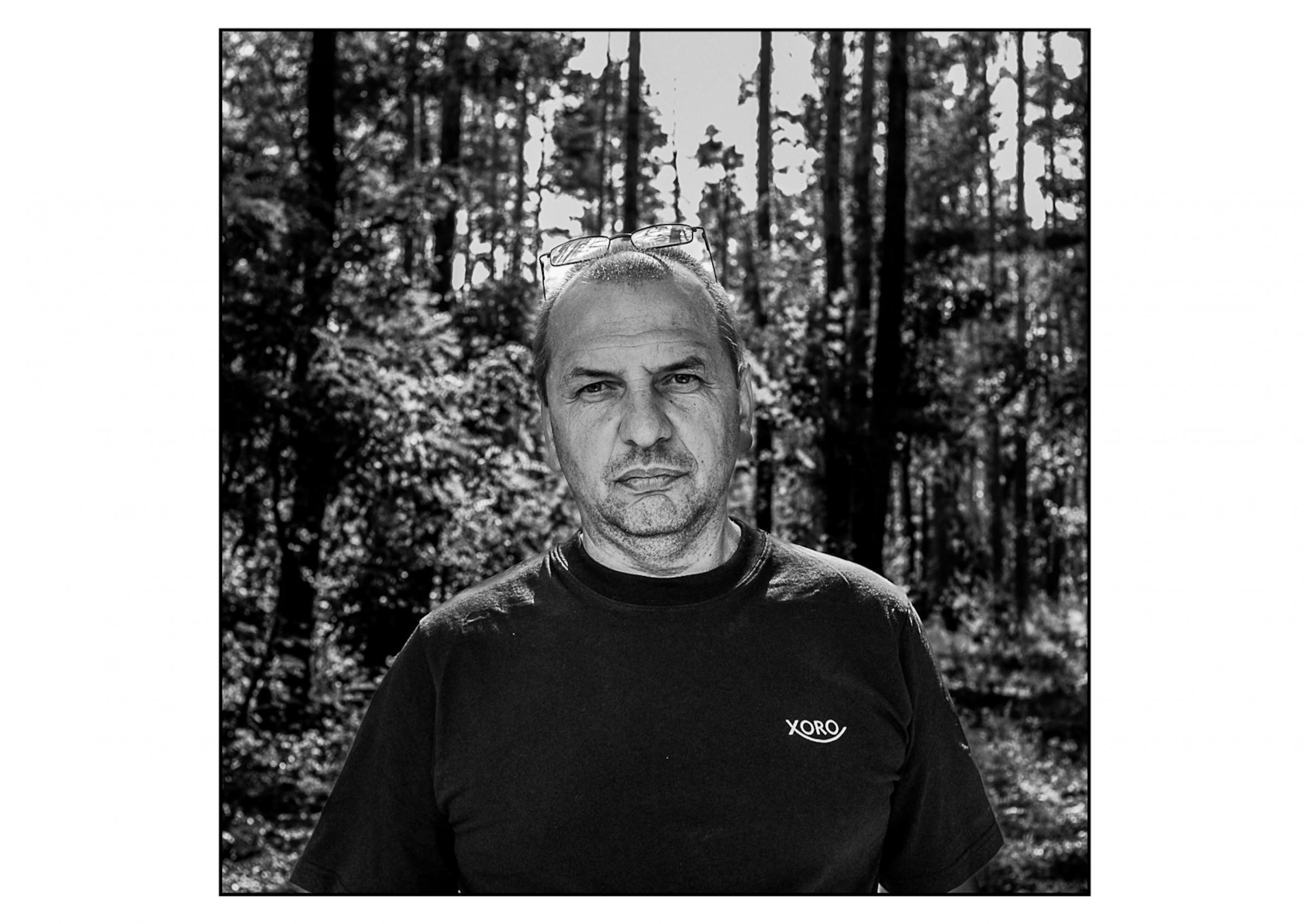

There I caught up with two villagers I have come to know during my visits over two years of covering this conflict, 54 year old Vadym Zherdetsky and 70-year-old Valentina Pompenko.

Vadym Zherdetsky. Picture: David Pratt

Valentina Pompenko. Picture: David Pratt

Village battlefield

Back during those first days of the invasion and battle for Hostomel their village of Moschun became a battlefield.

Zherdetsky still recalls the terrifying moment when two Russian rockets slammed down and exploded next to his family home.

“It was very frightening - only a stupid person would not be afraid. I was especially afraid for my grandchildren,” Zherdetsky told me, before going on to describe how he swept one of them up into his arms as the whole family rushed to escape the house and battle that was about to consume Moschun

It is estimated that in the ensuing battle some 30,000 Russians were pitched against a much smaller force of just over 3,000 Ukrainians, a Ukrainian brigade and battalion, respectively. Both Vadym and his fellow villager Valentina Pompenko in the months following the battle for Hostomel told too of listening to the sounds of battle coming from the airfield before it grew ever closer to Moschun as the fighting eventually engulfed the village.

It has been almost a year just since I last spoke with Valentina. Last March she was living in one of the 60 prefabricated homes that other returning residents to Moschun had to inhabit while waiting for repairs or rebuilding other homes often in sub-zero temperatures.

A few days agao when we spoke in the yard of her house she recalled again of how, her neighbour burned to death in his home just yards from where we talked. Today Valentina still draws her water supply from a hand cranked well and reads the poetry that has become her temporary escape from two years of war and which she is prone to reciting to emphasise a point in our conversation.

“My grandson is in the army on the frontline near Kherson, I’m very proud of him,” she tells me smiling, the expression on her face becoming more sombre as she tells of how after two years of war, she believes it will continue for a long time yet. Like Valentina his village neighbour, Vadym Zherdetsky too has a son on the frontline.

“He is recovering after being exposed to some kind of gas that was fired at them in the trenches," he explains as if he were recounting experiences from the First World War and not one now in 2024 that shows no signs of abating.

Over two years now ever since the battle for Hostomel, the tide of battle has ebbed and flowed in this war but currently Ukraine is facing perhaps the most precarious position it has found itself in since those first weeks of the invasion.

There are two main reasons for this. The first is that US military aid has been stopped for months, and it’s unclear if or when more will come.

Almost every Ukrainian you meet right now brings up this thorny issue of a lack of ammunition and resources. The second crucial issue is manpower with Ukraine already struggling to get people to fill frontline forces that are depleted after two years of fighting. Currently the country needs to find about 500,00 new recruits this year.

Eighteen per cent of Ukrainian territory is now currently occupied by Russia and more than 6.4 million Ukrainians are refugees. It’s all a far cry from a year ago when Ukrainian leaders were brimming over with optimism over the chances of Moscow’s troops back. But that counteroffensive failed to make headway, with opposing Russian forces now entrenched along the 1,000km frontline.

Soviet era plane sits alongside more recent and wreckage of Russian helicopter used in the assault on Hostomel. Picture: David Pratt

Pathway to victory?

Many international observers and analysts now argue that after two years of war there is no foreseeable pathway toward a battlefield victory for Ukraine, and that even with the imminent arrival of more long-range missiles or F-16s fighter planes this will not be enough to tip the balance in Kyiv’s favour.

Some say that by standing on the defensive this year, Ukraine can still inflict such losses on the Russians and if supplied with more Western weaponry, might still be able to counterattack successfully in 2025.

Frankly, it's hard to imagine any other option for the Ukrainian army. For months it has been up against an imposing Russian defensive line of trenches, concrete barriers and minefields stretching 15 to 20 km deep, preventing any armoured vehicle from piercing through.

Yesterday, Zelenskyy, speaking from Hostomel, thanked Ukrainians for their continued ccommitment to the war

"I am incredibly proud of each of you. I admire each of you. I believe in each of you. Any normal person wants the war to end. But none of us will allow our Ukraine to end. That's why when it comes to ending the war, we always add – on our terms,” said Zelenskyy.

"That's why the word "peace" is always preceded by the word "just". That's why in the future, the word "independent" will always stand next to the word Ukraine. We are fighting for this. And we will prevail. On the best day of our lives," Zelenskyy insisted.

During those opening salvoes of the war that day two years ago at Hostomel airfield, few realised at the time how in terms of Ukraine’s defence it would prove pivotal in preventing the fall of Kyiv. Had Russian troops broken through there and in places like Moschun then the gateway to the capital would have been open and the fate of Ukraine might have been very different. Today, Hostomel stands as a reminder of just perilous those times and the dangers Ukraine once again faces as this war enter its third year.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here