A PAUSE for reflection. As the transfer splurge in England racked up more than £1bn in some sort of gaudy telethon, as players one has never heard of signed for £20m-plus for teams one does not care about, as one wondered precisely where was Harry Redknapp and his car, his open window and his elbow . . . one had a thought for the days of the past and what it all means for the future.

As Sky and skies opened in a torrent of hype, rumour and loan signings, I spent my morning reading page 23 of the Sunday Mail of February 24, 1963. It featured a wonderful report from the estimable Allan Herron. It declared, bluntly and irrefutably, that “Scots now dominate the English soccer scene”. This sentiment was all in capital letters, of course.

In truth, it needed no emphasis. It was enough to consider the figures. In the first and second divisions of the English game (now called, of course, the Premier League and Championship), there were 44 clubs and they included 196 Scots in their squads. There were nine Scots at Manchester United, 10 at Liverpool and six at eventual champions Everton.

Read more: Mark McGhee: Ross McCormack still has Scotland future despite latest Malta snub

These statistics seem astonishing now but they merely formed the visible high point in a structure that held English football together. The English leagues were formed on the back of Scots leaving their native land for lucrative playing fields down south, even though initially they conformed to the sham of being amateurs.

Read more: Mark McGhee: Oliver Burke has the X Factor - but must wait to be a Scotland smash hit

At first, they took a passing game that refined and changed the English game and helped build a league that started in 1888. Scots became a staple of that league. Willie Groves set the first transfer record by moving from West Brom to Aston Villa for £100 and his fellow Scot, Andy McCrombie, broke it when he moved from Sunderland to Newcastle for £700 in 1904.

Scottish clubs were highly involved in the escalating trade. In February 1911, Falkirk sold an Englishman, John Simpson, to Blackburn for £1800. The next Scot to set a record, however, was Billy Steel when he moved from Morton to Derby County in September 1947 for £15,500.

Denis Law broke the record twice in his Manchester City-Torino-Manchester United switches that totalled £215,000. The next and last Scot to set the record was Andy Gray when signed for Wolverhampton Wanderers from Aston Villa in September 1979 for £1,469,000.

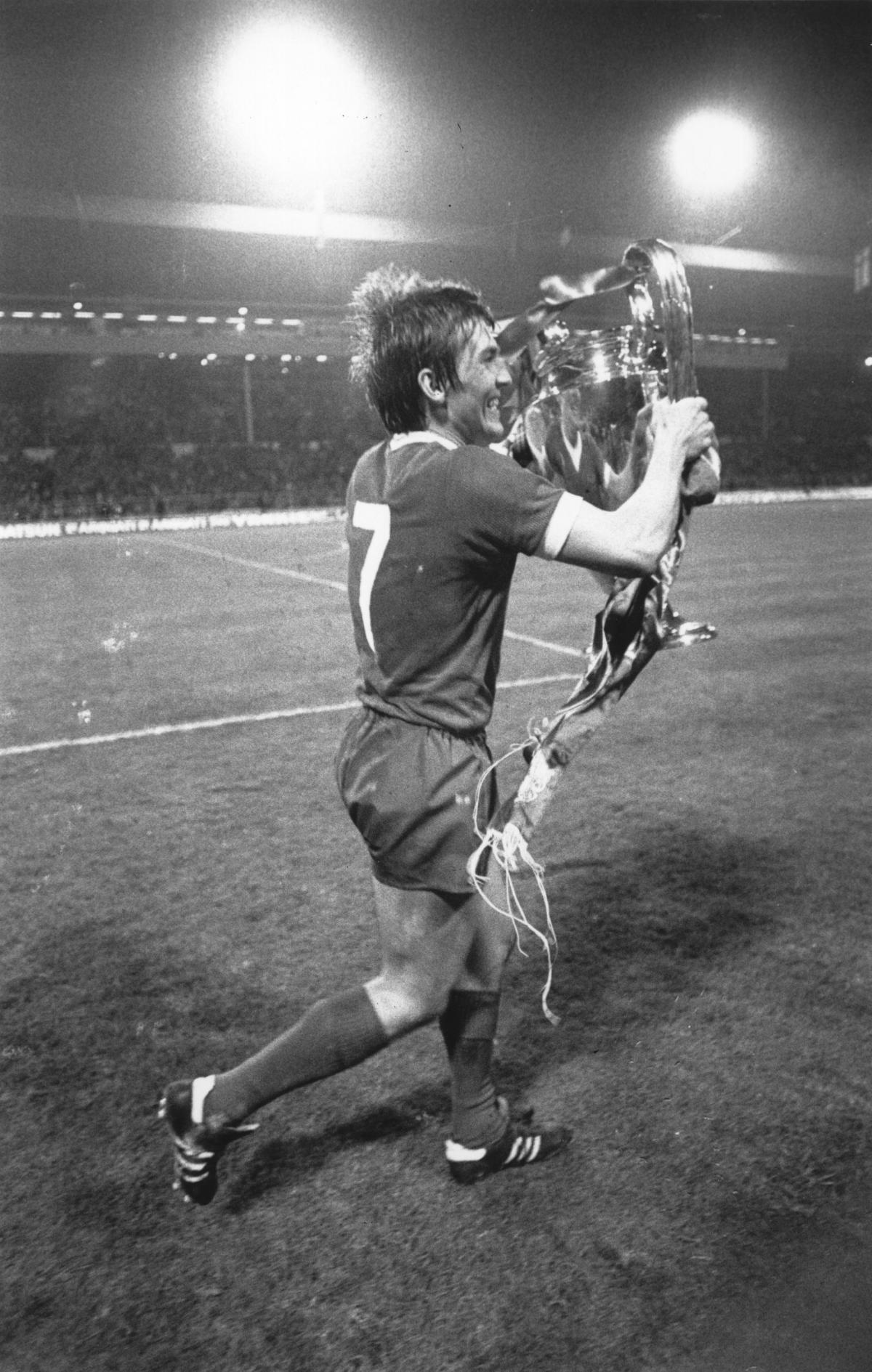

These names and fees are glorious echoes of the great days of great Scots in a great league. But the more significant signings for the Scottish game happened later. Kenny Dalglish (to Liverpool from Celtic for £440,000 in 1977), Lou Macari (Celtic to Manchester United for £200,000 in 1973 ) Martin Buchan (Aberdeen to Manchester United for £120,000 in 1972), Colin Stein (the first player to feature in a £100,000 transfer between Scottish clubs when he moved from Hibs to Rangers in 1968 and subsequently sold to Coventry City in 1972 for a similar fee) Ray Stewart (Dundee United to West Han United for £430,00 in 1979) were central to a new reality in the Caledonian game.

Players routinely now in the 1970s and beyond went south in their prime. It is extraordinary, for example, to realise that all the Lisbon Lions spent the best days of their careers with Celtic. The retention of their registrations meant it was difficult to leave a club that wanted to keep a player. There was a disparity in wages between Scotland and England but not a chasm. Many top players played the bulk of their playing peak in Scotland and were largely content to do so. But it then became the norm for the best players to move south.

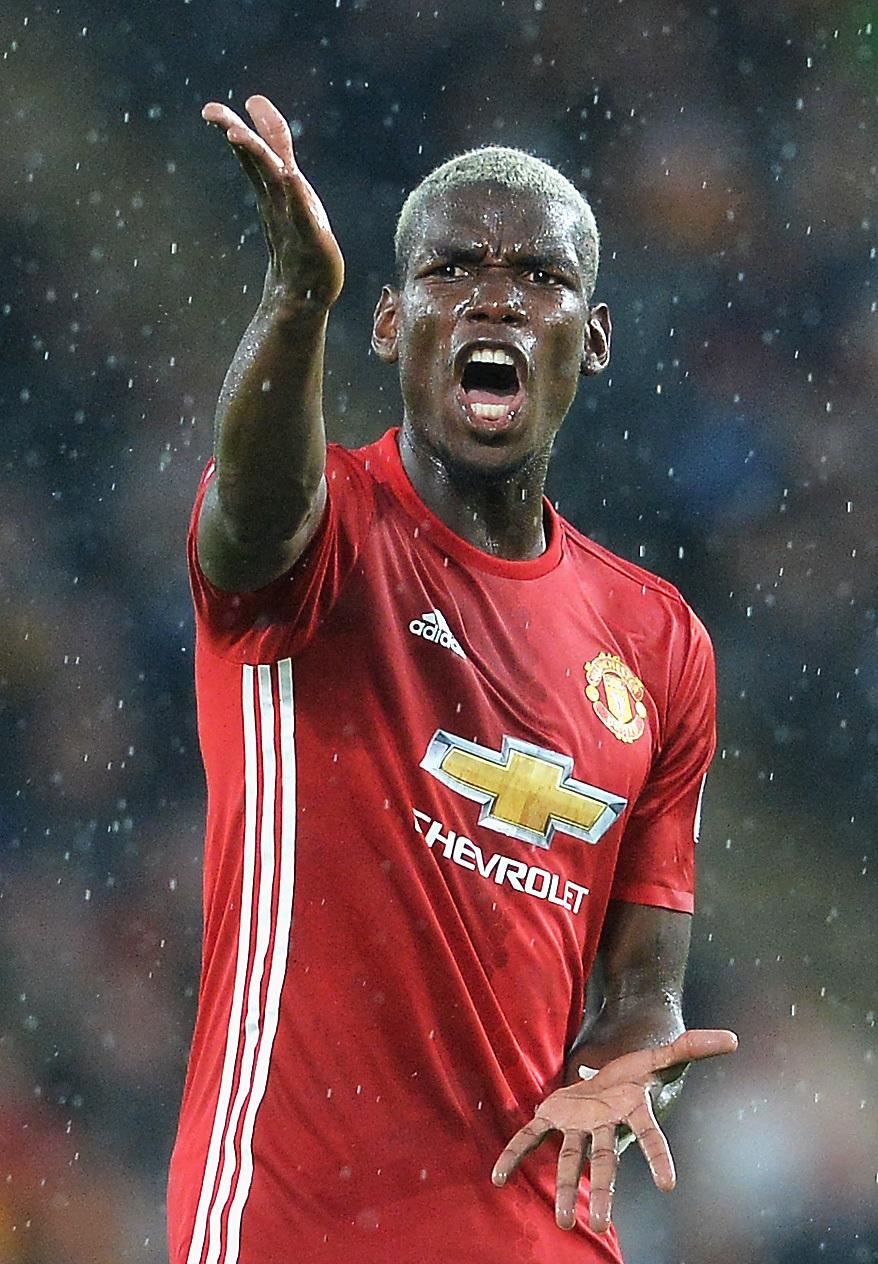

But recent years have witnessed developments that have become damaging to the Scottish game. There has been justifiable interest in Oliver Burke’s £13m move to Red Bull Salzburg from Nottingham Forest that has set a record for a Scottish player. But this and the big deals involving Ross McCormack (now at Villa), Steven Fletcher (Sheffield Wednesday) and Justin Rhodes (Middlesbrough) did not bring money into the Scottish game.

Furthermore, departures of Scottish player to England now regularly involve minimal fees and fit two categories. The first is the journeyman heading to a lower division, the second is the young prospect being identified early (such as Fraser Fyvie, Jack Grimmer, Matt Kennedy, Stephen Kingsley) and lured south on a small fee even though their potential is substantial.

Scottish clubs thus lose in this increasingly febrile market. Their development players can be plundered at a relatively low cost by English teams who routinely spend millions on what one chief executive described as “a punt”. Any replacement for these departures, of course, are not easy to source in the Championship or above.

Front the inception of the Football League, England has always been an attractive option for the Scottish footballer.

One lesson of the 2016 transfer window is the reinforcement of the reality that Scots with Scots clubs are no longer such an attractive proposition for English clubs. The other certainty is that when English clubs want a Scottish youngster, they target him early and sign him for a sum that does not make a dent on the £1bn telethon.

The money flows from English club like a burst standpipe. It is not lapping up on Scottish shores. One can wonder at, even be critical of the extravagance but also be rueful that Scotland does so largely as onlookers rather than as beneficiaries.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel