Barbed wire and paintbrushes: eight pictures that tell the story of the First World War

FOR four years now, communities across the UK have been marking the centenary of the First World War. But as the 100th anniversary of the end of the conflict approaches, the last word should surely go to the soldiers themselves.

Soldiers like Lieutenant John H Geiszel, one of only two officers in his company who wasn’t wounded or killed. Or Major John Empson Tindall who remembers the flames and gas at the Battle of Armentières and the desperate attempt to escape them. Or Lieutenant Nellis P Parkinson who remembers the rats digging and squealing in his dugout. “We wondered why poison gas did not exterminate them,” he said, “But they seemed to be immune.”

All of these soldiers, and many more, are represented in a new exhibition which opens at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow this weekend. The aim of the exhibition is to tell the story of the war - from the misplaced optimism of the early days to the muddy, bloody realism at the end - through paintings and drawings by ordinary combatants from all sides. This isn’t the story told by the official artists, or the one that appeared on the propaganda posters; it isn’t slick or glorious; it’s real and dark and disturbing and occasionally blackly funny.

To mark the opening of the exhibition, we have chosen eight of the pictures that will go on show, which mostly come from the private collection of Joel Parkinson, the director of the World War History and Art Museum in Alliance, Ohio, and grandson of the Lieutenant Nellis P Parkinson who missed the sniper’s bullet. We begin with the picture that started Joel’s collection and features his grandfather: Rainbow Machine Gunners Moving to the Front.

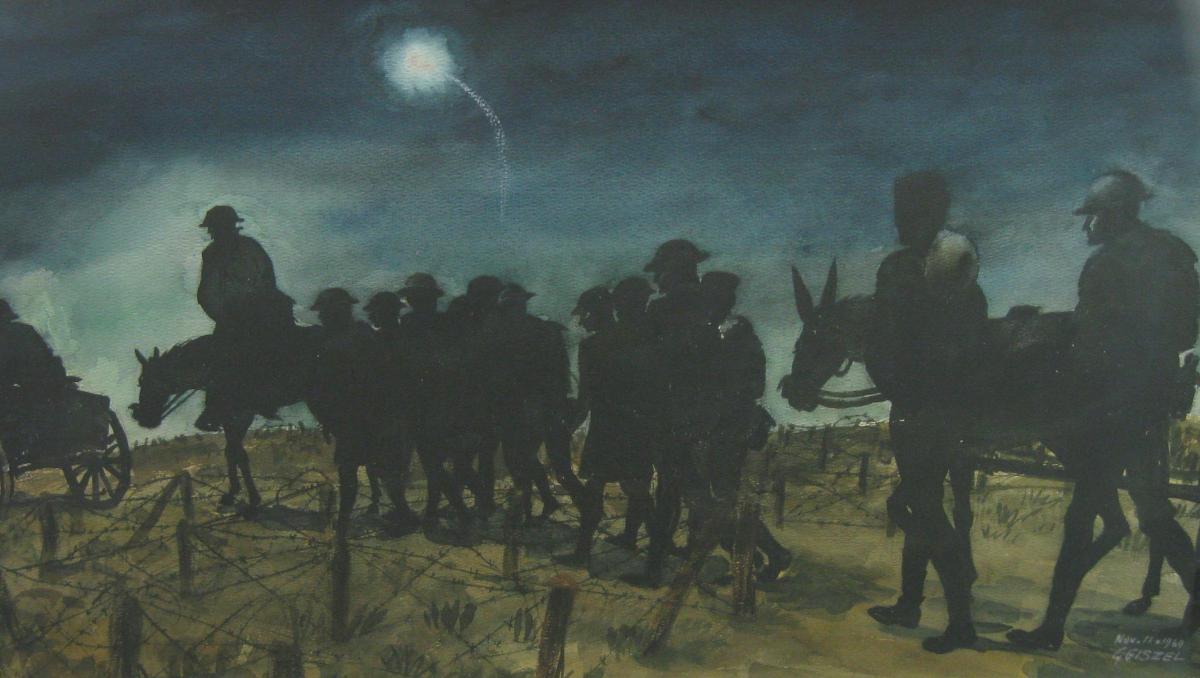

Rainbow Machine Gunners Moving to the Front, by Lieutenant John H. Geiszel

A company of Allied soldiers marches through the mud. Above them, a German flare lights up the sky. At the front, on a horse, is Lieutenant Nellis P Parkinson. He may be asleep as riding was one of the few opportunities soldiers had to rest on the Western Front. This is one of eight horses that Lieutenant Parkinson went through in six months, but that’s what it was like – the casualties were high for everyone on the front line, animal or human. Parkinson’s company - Company D, 151st Machine Gun Battalion, 42nd Rainbow Division – sustained 65 per cent casualties. Parkinson himself was one of only two officers in the company that weren’t wounded or killed.

Speaking from his home in America before coming over to Glasgow for the exhibition, Joel Parkinson says he inherited the painting from his grandfather and says it is one of the most personally prized in his collection.

“Lieutenant Geiszel, a fellow officer in granddad’s company, painted him leading the machine gun squad through barbed wire to the front at night,” says Parkinson. “I grew up listening to my granddad’s war stories and admiring that painting. I eventually inherited it and now proudly display it in my office, when it is not on loan.”

As the family historian, Parkinson, who was 18 when his grandfather died, knows the story of how he become involved in the war. “He signed up in 1917, right after the United States declared war on Germany, and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. Before he was commissioned, he had two minds – he was eager to be commissioned, but reluctant to get his hopes up that he was going to make the grade. All along the way, he talked about all these other officers he travelled with and he was like the sole survivor from these different groups that travelled there. One of the things he talked about was going over the top and how they would psych themselves up and think ‘I might die but not today. One more day.’”

Portrait of a German Infantryman Off to War, by unknown German artist.

When the First World War broke out in July 1914, the British said the war would be over by Christmas. The Germans said their troops would all be home before the last leaf of autumn fell. We all know how reliable those promises were, but this painting of a young German soldier, of the 125th Infantry regiment, was done in the early days when there was still optimism, strength and hope.

“They were all cocky and expecting to win,” says Parkinson, “So here we have this German soldier and you’ll note the flower on his uniform – it was common practice, particularly among Germans, when troops went off to war that their women, girlfriends, mothers, wives, would give them flowers, so this guy was being mobilised in the earliest part of the war.”

Parkinson has wondered over the years whether the soldier in the picture survived. Given the statistics for German casualties – seven million of the 11 million soldiers mobilised ended up as casualties - the chances are not high. Did this young man, full of pride in 1914, come back from the war? Probably not.

Walking the Plank by Gunner FJ Mears

In some ways, this is the most important picture in the exhibition because it gets right to the heart of why art by the soldiers is important. The picture is of Ypres in 1917 and the artist, FJ Mears, said he wanted to express the true spirit of the war as the soldiers saw it and not as seen by the conventional artist; it is a deliberate contrast to the glorified propaganda posters.

The painting also gave Joel Parkinson the idea to start collecting soldier art. “The idea for Brushes with War came to me when I bought the painting by Mears,” he says. “I realised I’d never seen other works by the actual troops who served so my quest to acquire original art by the soldiers of the First World War began. I realised that in museums I had seen a lot of First World War illustrative art and propaganda posters and official art but not really much in the way of art by the actual troops and so I thought I'd better make it my quest to acquire what I could of art by soldiers.”

Parkinson now has more than 300 pictures and paintings, most of which were painted at or near the front line. Sometimes, the soldiers would draw or sketch in the trenches and then add paint later on and often they had to improvise materials and paper. For this reason, the art by soldiers is often small; the pictures also tend to be stark and subdued – there is none of the glory of propaganda. And there is very little gore, as a mark of respect to their comrades.

Parkinson says it is a unique and powerful blend. “I tell people all the time: a lot of you will take your children to a photo studio and get pictures taken that you can send people and they’ll be picture perfect and they’ll be really nice but they’re not what your kids look like day to day. Whereas you might have a snapshot of them eating at a table or playing in the backyard and that’s more reality. That’s the comparison I draw – the official artists are kind of like the picture-perfect portraits, but what these guys painted is more like the snapshot or capturing of reality.”

HMS Birmingham Ramming U-15, by TJ Minshull

The muddy, deadly trenches of the Western Front in France have become the most enduring image of the First World War, but the war was fought in many other countries too. It was also fought in the air, and – as this painting shows – at sea too.

The picture shows an incident on August 9, 1914 when the British cruiser HMS Birmingham spotted a German U-boat through the fog off Fair Isle in the North Sea. Apparently, the U-boat’s engines had failed and banging could be heard from inside as the crew attempted repairs. HMS Birmingham rammed the U-boat and cut it in half.

Twenty three men were killed. It was also the first U-boat the Germans lost in the war. Later, the decision by the Germans in 1917 to escalate the war at sea with the use of unrestricted submarine warfare drew the US into the conflict and ultimately lead to German defeat.

Parkinson says the picture is accurate in terms of what happened on the day (except that in reality it was foggy); he also says the U-boat hints at the technological advances that were made in the First World War and other wars.

“One of the sad things is that the First World War saw the advent of air warfare, chemical war, flamethrowers and tank warfare,” he says. “The list goes on.”

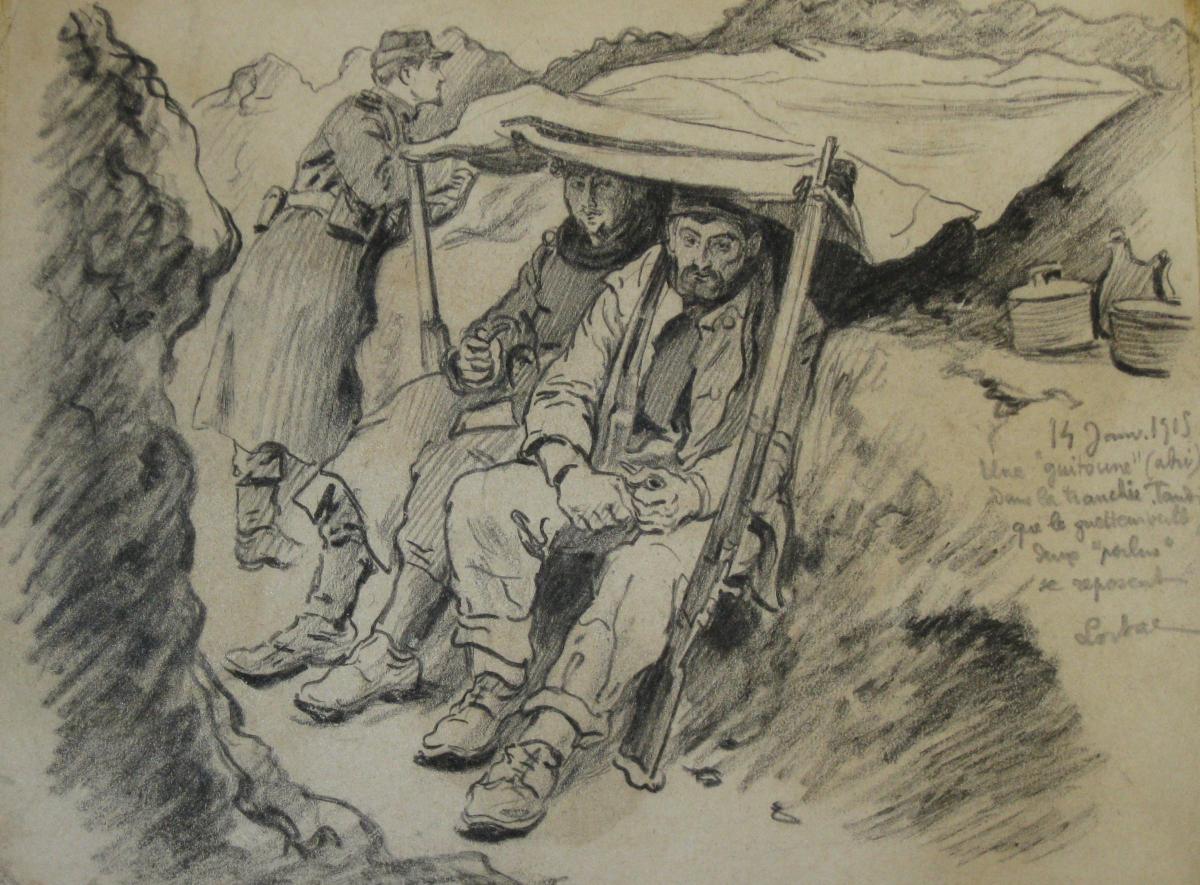

3rd Battalion Chasseurs, French Army, by Sergeant Robert Lortac

This picture says it all about what it was like to be in the trenches: the mixture of doing nothing and doing everything to survive, the drudgery and the danger. One soldier is keeping a constant look-out into no man’s land, the others are slumped under a makeshift tent, tired and resigned.

The sketch was the work of Sergeant Robert Lortac, who drew it at Artois in May 1915 after the Western Front had solidified into hardened positions. For the next three years, the trenches would hardly budge.

“One of the things that this gets at, which is repeated in a number of the paintings, is this odd combination of boredom along with alertness that you need to survive,” says Parkinson. “They couldn’t take a nap or zone out – they would have to fight this boredom without being distracted.” The artist knew the dangers himself: a few months after drawing this picture, he was wounded when artillery shrapnel ripped off part of his shoulder.

I Don’t Wanna Get Well, by unknown

From the start, women were involved in the war effort. Pressure from women for their own uniformed service began in August 1914 and the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was established in December 1916. Fifteen months later the Women’s Royal Air Force was set up and in total, over 100,000 women joined Britain’s armed forces during the war.

Nursing was the other major contribution made my women – by 1918, more than 17,000 nurses had served close to the trenches, in military hospitals and in the UK – and this picture shows one of those nurses as drawn by an unknown injured soldier.

“One of the interesting things about this picture,” says Parkinson, “is that it kind of combines humour and horror because he is obviously anticipating the horror and misery of going back to the trenches and he humorously says he would rather have this nurse than what he has to go back to: the rats and the lice and the mud and the rain.”

Rats, by Gunner FJ Mears

An entry in the diary of Joel’s grandfather from 1918 makes it clear what it was like to live with the trench rats. “Rats abounded,” he wrote. “We heard them at all hours of the night digging or squealing behind the board walls of our dugouts. The minute it became quiet in a dugout, the rats would peek out from a dozen holes and steal forth, foraging for scraps of food. We wondered why poisoned gas did not exterminate them, but they seemed to be immune.”

Joel Parkinson says the rats made life miserable for soldiers like his grandfather. “One problem was if you didn’t bury soldiers deep enough, rats would dig up the grave,” he says. “It was really grim. People today, particularly here in the United States, that aren’t as aware of the First World War as folks in Europe are, have no clue what men went through.”

American infantryman Near Grivesnes, by Maurice Mahut

Compare this picture of a young American soldier in 1918 with the young German soldier from 1914 for there are similarities and differences. Both of the soldiers look confident, cocky even, but the German soldier was posing at the start of the war, whereas this US soldier was painted four years later, in June 1918, at a crucial point in the conflict: the Americans were coming.

“It was painted by a Frenchmen and the American looks confident,” says Parkinson. “He’s standing upright, he’s clean, he’s not shot-up or beat-up and it’s interesting because the Americans at this point are where the British, French and Germans were in 1914: we can do this. In fact, they did, because they were adding hundreds of thousand of troops to the balance and they weren’t jaded and worn out. The Germans, British and French were bled dry.”

Five months later, the First World War was over.

Brushes with War is at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum until January.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here