ON THE 11th November, the bells will tell their story. They will ring first in Dunblane at half past nine in the morning, followed a few minutes later by Edinburgh, then Aberdeen, Glasgow, Inverness and Stirling. It will be a solemn act of remembrance to mark 100 years since the bells were rung in 1918 at the end of the First World War, but there will be an echo of the future too: the next generation who have signed up to ring the nation’s bells in the years to come.

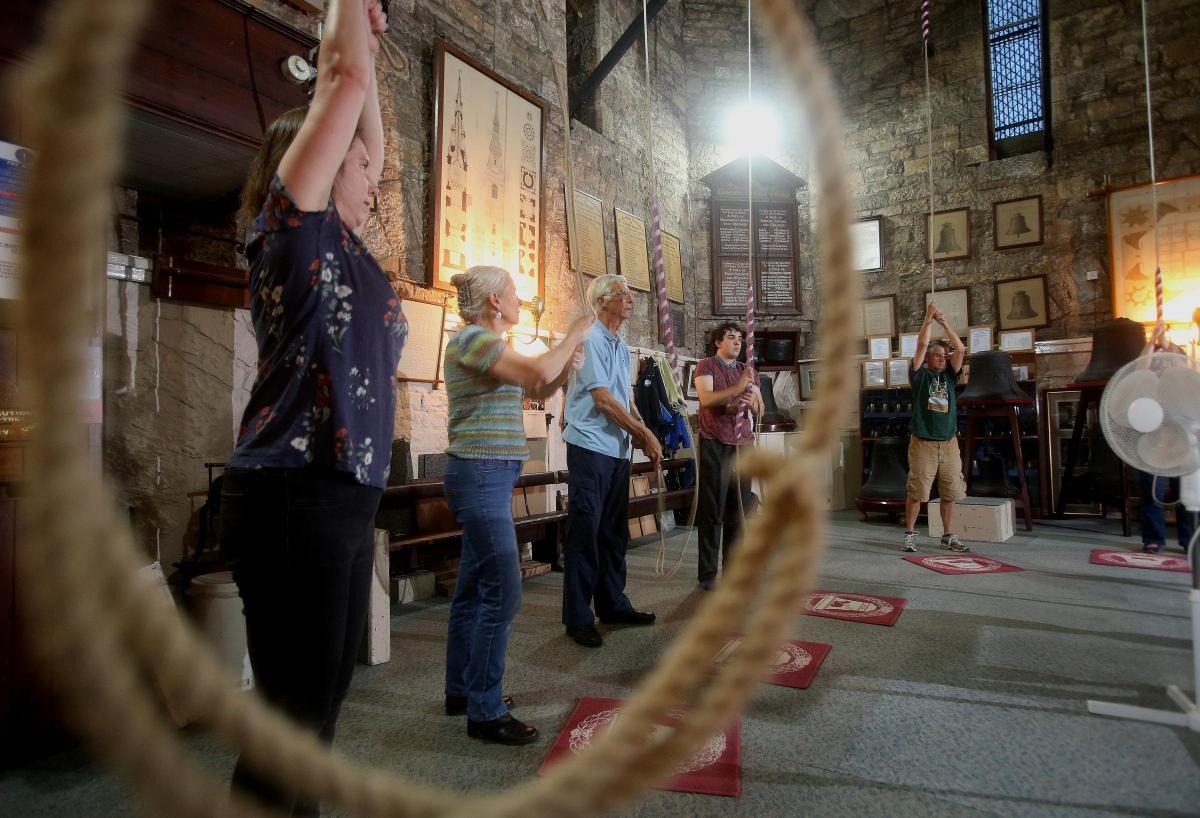

The details of the story lie at the top of the long, narrow staircase to the top of the tower of St Mary’s Cathedral in Edinburgh where the church’s ringers are meeting for their regular Thursday night practice. Everyone has heard church bells ring out at some point but not many get to see how they work close up but here it is. A space about the size of your average house. In the middle are mats and boxes arranged in a circle. Above is an arrangement of ropes that disappear into the roof to meet what we know is up there: 20 tons of bells with names like Fortitude, Faith and Holy Fear.

The ringers are going to show me how it works and it’s not easy. In fact, it can take something like six months to learn how to ring a bell proficiently. In one corner of the room is a big metal structure that beginners use to practise on (it’s not attached to a bell) and I have a go. Hold the rope with both hands, I’m told, pull down until the bell is in the up position, go with the back stroke and then catch it on the way down with the “sally” (the fluffy bit). Remember to bend your arms. Don’t hold the rope too tight. Hang on, I’m doing it wrong. This is tricky, and it’s only the beginning.

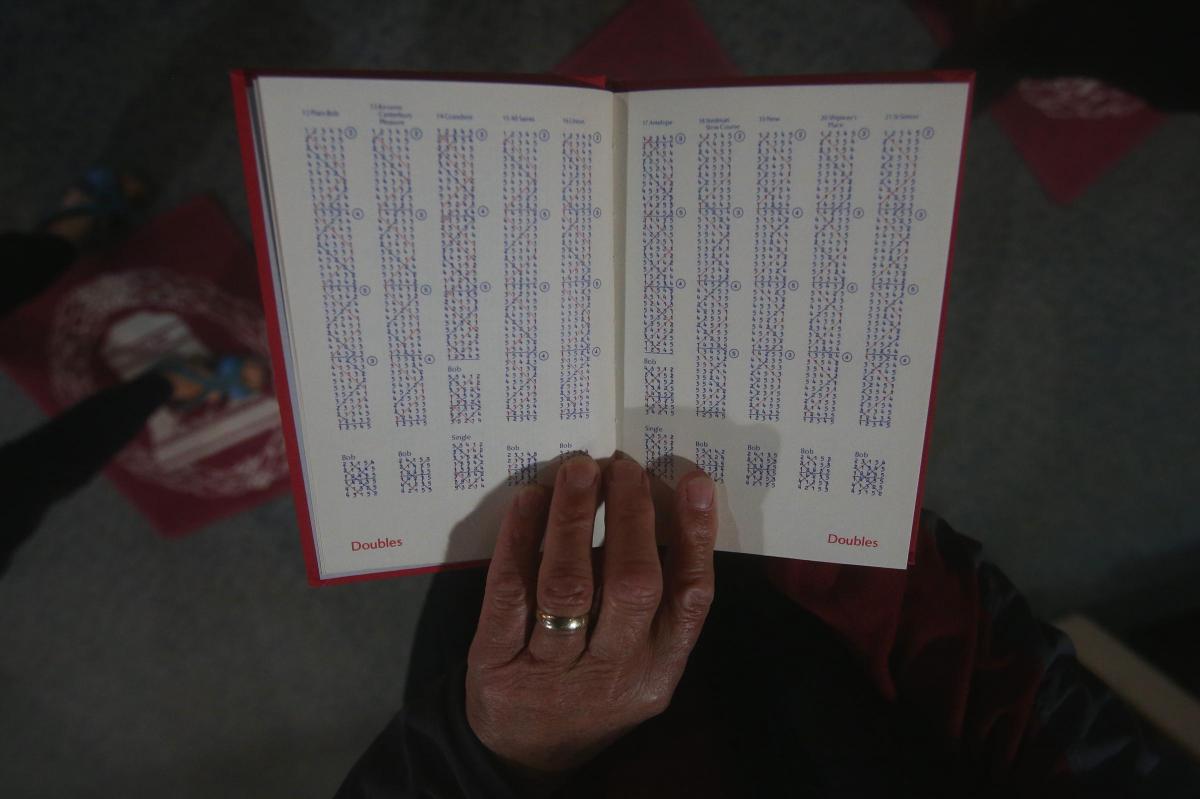

My instructors are Mr and Mrs Bell (I ask them if they believe in nominative determinism) and they explain the details of how bellringing works. I assumed the difficult bit would be learning how to handle the rope and prevent the bell from swinging out of control, but that’s only the half of it. Once you get that technique right, you then have to master what are known as “methods” – effectively, the patterns ringers follow. They show me a book filled with some of the methods they use and it’s impenetrable, a succession of numbers that correspond to the bells. It looks like the Enigma Code.

Barbara Bell, who’s 65 and has been a ringer for 40 years, tells me more about how it works. “It becomes a mental mathematical exercise,” she says, “because the bells change order but they change in a very regular fashion and there are various different methods which we give names to. You learn the pattern off by heart and it’s a bit like a knitting pattern with threads going in different directions. It’s quite mathematical – it’s not a musical thing.”

That is interesting: mathematical not musical. I go round the ringers one by one and ask them to tell me what they do for a living and it’s quite surprising. Chemist. Web developer. GP. Science teacher. Mathematician. Barbara’s husband Ian Bell – who’s the chemist - tells me there are lots of people from the sciences who ring bells. It’s probably OCD or something like that, he says; they like the order, the patterns, the rules.

But there are other, more worrying patterns to bellringing in Britain: like the fact that most volunteers are older and there aren’t enough ringers for the bells that need to be rung. There are some 6,000 bell towers across the UK with each needing 10 to 15 ringers, which is a lot of ringers.

One of the problems, according to another of the ringers here tonight, 53-year-old Tina Stoecklin (she’s the web developer) is that the bellringing community wasn’t good enough at recruiting 20 or 30 years ago and is now suffering the consequences. “We relied on people finding us rather than us finding people,” she says, “and we are slowly waking up to the fact that we need to do more. We still don’t have enough ringers.”

Another problem has been the decline in the traditional recruiting ground for ringers: church congregations. It used to be that boys would gravitate to ringing from the choir when their voices broke; young people would also follow their church-going parents into ringing. This is how it went with another of the St Mary’s ringers, 72-year-old Terry Williams, who taught his two sons to ring. “You have to breed ringers,” he jokes, “otherwise you can’t find them.”

And then there’s the image problem. I ask the ringers what annoys them most about how people see bellringing and they bring up the Mars advert in which the ringers hold on to the ropes and go flying up into the roof. That never happens, they say. And then there’s the problem of how young people might look at ringing. “It’s not seen as cool,” says Tina Stoecklin, “and apart from anything else, it’s attached to a church.”

But here’s the good news. Last year, as part of the nationwide events to mark the centenary of the First World War, a new campaign was launched across the country to commemorate the 1400 British bellringers who died in the war but also to recruit the same number of new ones. And it has been a stupendous success, with way more than 1400 coming forward across the UK – in fact, to date, the campaign has recruited some 1700 new ringers.

I meet some of them when I visit another group of ringers at St Mary’s Cathedral on Great Western Road in Glasgow, including 29-year-old Neil Aitken, who’s been ringing for seven months, and 46-year-old Catriona James, who’s only been doing it for a few weeks. Both of them are realising that bellringing is not easy.

Catriona first got involved when she heard the recruitment campaign mentioned on The Archers. “I’d always thought it would be something I’d be interested in,” she says. “People have been ringing bells like this for hundreds of years and technology can’t change that – you can’t move a ton of bell without a rope.”

She also wanted to learn a new skill. “I have two children, who are 10 and 12, so I have evenings free but there’s a discipline to it as well. When I started I thought that once you learn how to ring the bell, that was the difficult bit – but I’ve been coming for eight weeks and I can’t ring the bell yet. You then realise you have to learn the methods and people have been ringing for years and they have a language, a shorthand.” She is enjoying herself though, and thinks it is good for her mentally. “I can see the challenge,” she says.

Catriona is also realising that, despite the traditions of ringing, there is a modern side to it too. She has an app on her phone, for instance, that is helping her understand the methods; she also likes the fact that she is learning to ring at St Mary’s in the heart of Glasgow. The image of ringing may be of a bucolic England, but this is ringing urban style. Look, says Catriona, you can see the kebab shop from here.

Neil Aitken has been learning for a little bit longer than Catriona and is relishing the methodical, scientific side to it. Neil has been a member of the congregation at St Mary’s for about three years and got his first glimpse of the bell-ringing room when he and some friends were showing a Muslim group round the church as part of an inter-faith event. That’s when he got the idea that he might like to try bellringing himself.

Seven months in, he is enjoying himself even though he acknowledges it isn’t exactly a typical hobby for a 29-year-old. “It is kind of an odd thing to do,” he says. “But it’s harder than it looks. I’ve been coming every week for six months but it takes years to be proficient. And you have got to get it right because these bells are several tons.”

Neil, who works in a call centre, is also drawn to the technical side of ringing – he likes the coordination of it and the patterns and timings – and this is something I see in a lot of the other ringers too. Before coming here, I expected the ringers to be a romantic bunch whose hearts soared at the sound of the bells, but far from it. They are a methodical, logical group and asking them to get all romantic about the bells is like trying to get a truck driver to get romantic about the wheels on his lorry. They take a much more technical and serious approach to the subject and the ropes and bells are the tools of their trade.

They are not averse to change though – far from it. Last year at a meeting of the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers in Edinburgh, the organisation agreed to modernise its structure and rules. Tina Stoecklin tells me that the governance had become a bit old-fashioned and there had been rumblings for a long time about the need for reform.

“It was too big and had a lot of arcane rules and procedures no one understood,” she says. “It was also resistant to change and not much would happen. It had to become more modern. It wasn’t keeping up with technology and the needs of ringers, although the biggest change to bell ringing is the change to church attendance. There are also more competing interests.”

The trick, says Tina, is to make ringing fit in with how people live their lives now and there’s evidence it’s happening. However, one of the other appeals of ringing is surely the way it fits into the past and the fact that there is a thread of continuity from history. One of the ringers tells me that someone from the past who learned how to ring 300 years ago could walk into any bell tower in the country today and pretty much pick up from where they left off. There aren’t many other jobs that you could say that about.

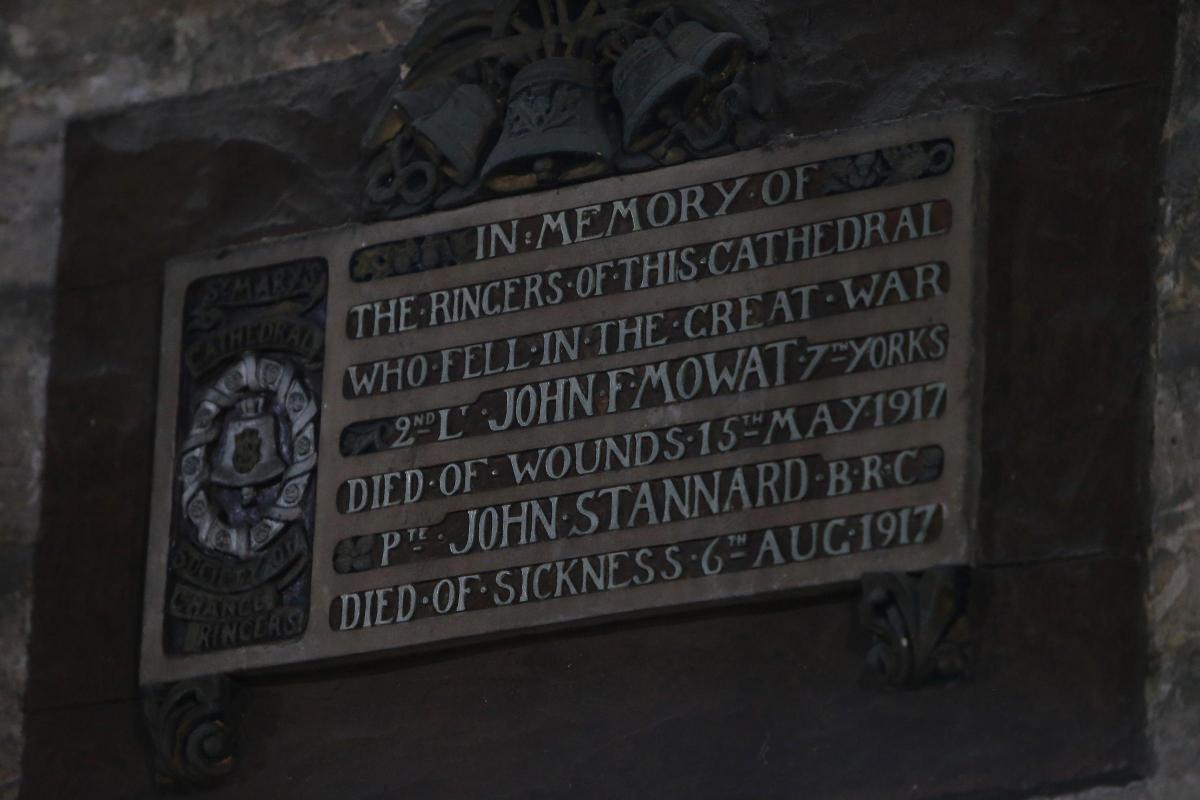

The connection to the centenary of the First World War has also obviously brought bellringing to the attention of more people. On the wall of the ringing room at the cathedral in Edinburgh is a plaque in memory of two of its ringers who died in the war: John Mowat, who died of his wounds in May 1917 and John Stannard, who died of sickness in August the same year. This is a pattern repeated all over the UK: men who went away to fight and never came back, leaving a gap in their church tower, their bells unrung.

This huge loss also brought about some other changes in the ringing community. Before the First World War, ringing was essentially a man’s business, but as the casualty numbers grew, more and more women stepped in to become ringers and now the community is about 50/50 men and women.

There are some limits to the modernisation though. I ask the ringers in Edinburgh whether you could, or should, ever automate the bells and the word ‘no’ echoes emphatically round the tower. They do recognise, though, that they still need more young volunteers, but think more people should give this curious, fascinating custom a try. And when they start ringing, I can see the appeal. The intense, meditative look on their faces. The complicated, mathematical patterns in their heads. The fact that none of it comes easy. And the sound: the sound of the past, and the future.

For more information about becoming a bellringer, see www.sacr.org or email publicity@sacr.org

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here