"REMEMBER,” Lorna Cooper writes in her book Feed Your Family for £20 A Week, “running an empty freezer is more expensive than running a full one.”

It's a comment that's a trigger for a new phase in my relationship with my freezer. In fact, the big change that goes on when I try to follow her budget cooking plan is that suddenly it's stuffed – full of bags of frozen vegetables and fruit, a ready to roast chicken, frozen fish, half-baked baguettes. Cooper, a 39-year-old mum of three children and two step-children from Paisley and guru of low cost cooking, talks about making “your freezer your friend”. Well, my freezer and I have been, till now, frosty acquaintances. It doesn’t help that we have put it inside a storage room which is not even in our flat, but down the bottom of the shared stairs, and have to, effectively, leave our home to get to it.

I also come to the realisation that I am a fresh food snob. For decades I have been buying almost all my food fresh, as if that were some religion. Yet, when, worried about what a frozen food diet would mean for my family, I checked out the research, I found that fresh fruit and veg were not, as I believed, nutritionally better. One study in the Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, revealed that the frozen versions of fruit and veg consistently outperformed the "fresh-stored" ones in tests of several key nutrients.

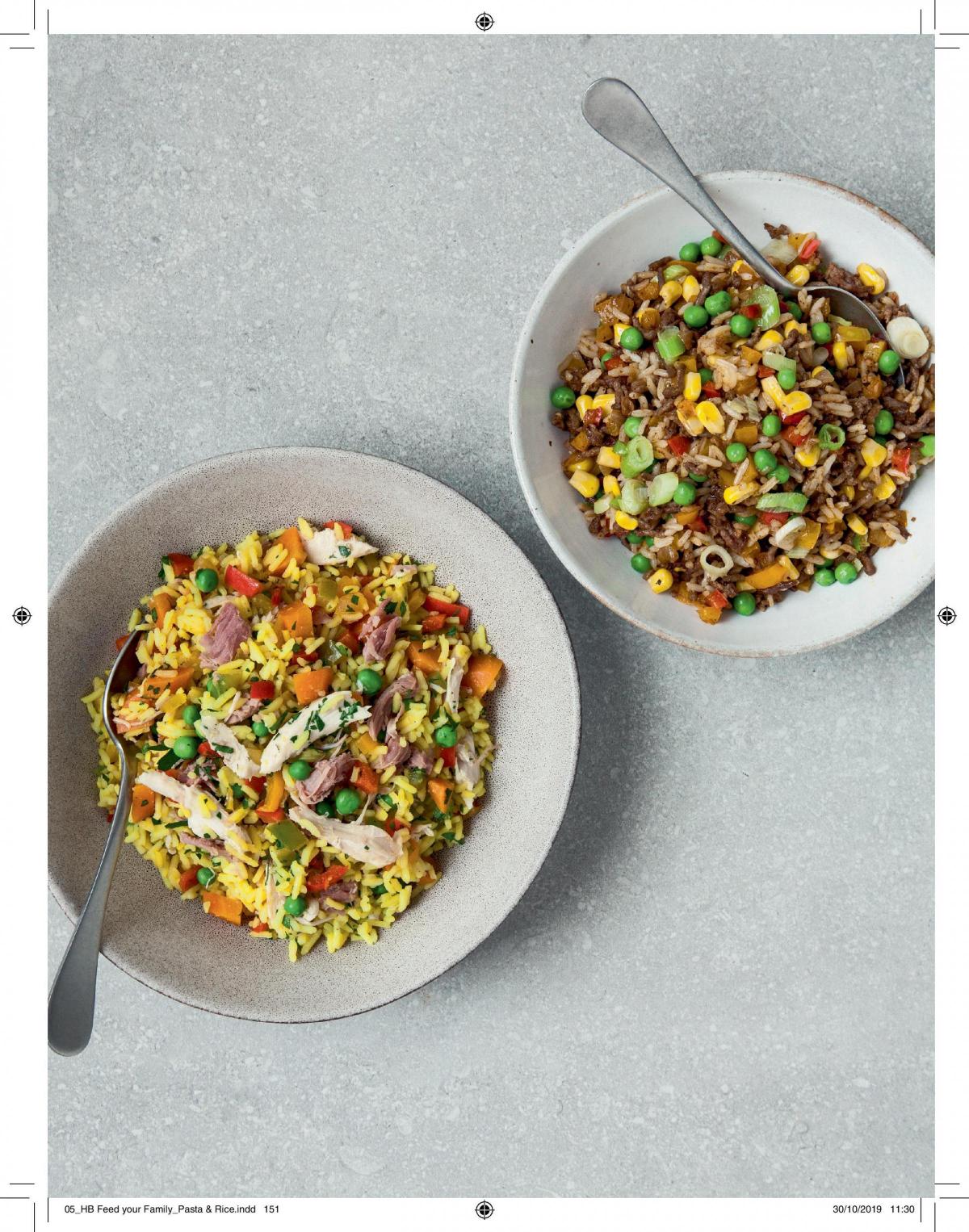

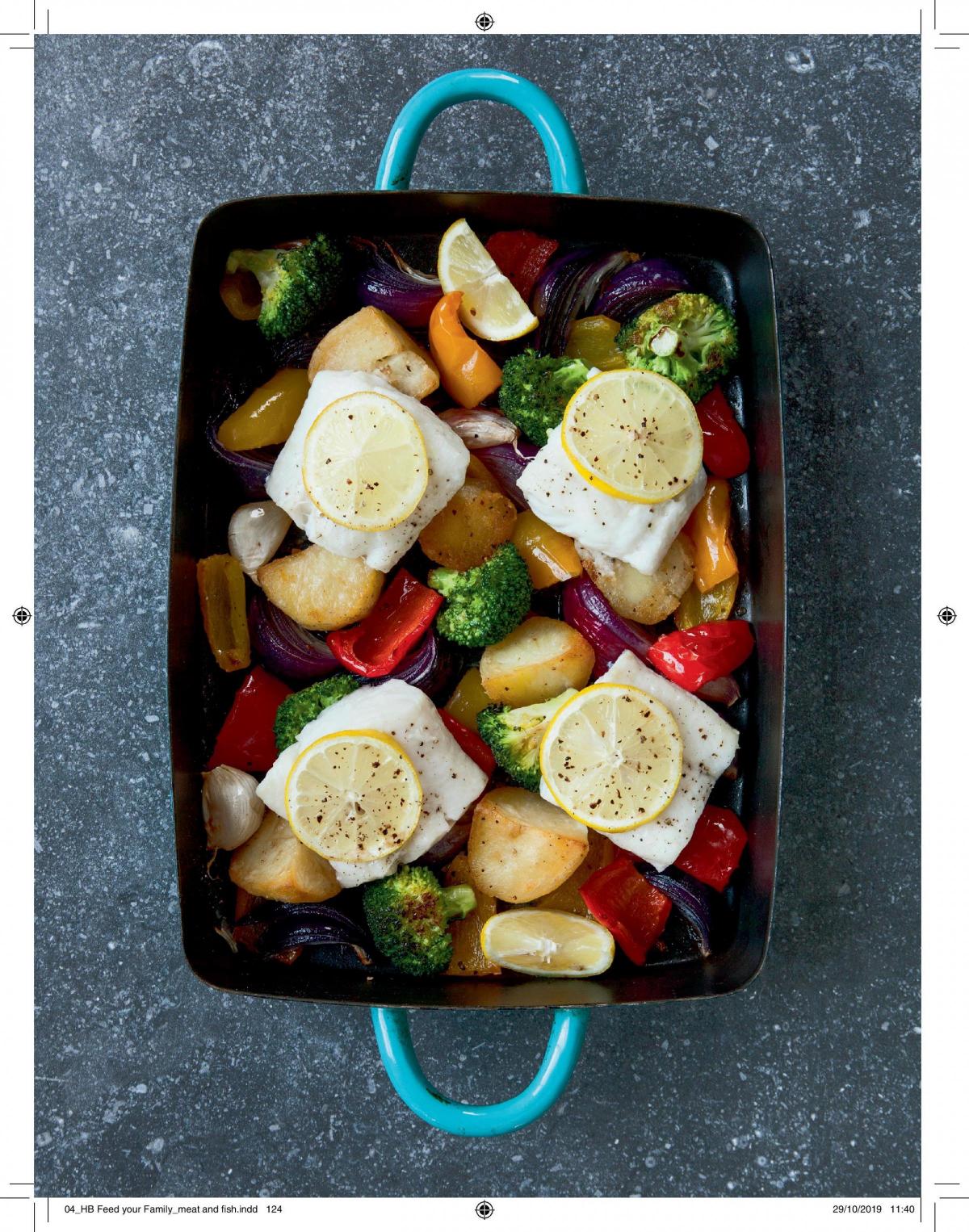

Cooper’s approach is all about cooking from scratch, planning, bulk-buying, a touch of batch-cooking (though her message is more about making two of each recipe each time you cook, rather than spending your Sundays cooking for the whole week), bulking out expensive ingredients like meat with cheaper ones like lentils and oats and working your leftovers.

A first glance at her planner left me stunned by the deals she was getting. 500g of spaghetti for 20p, 60 frozen sausages for £2.73 and 3 x 900g chicken breast fillets plus 2 x 1.7kg ready to roast chicken for £5, on a 5 for £15 deal. I was impressed by the way she stretches what she buys. Whole meals for four are centred on a single chicken breast fillet (chow mein or jambalaya). If you were a carnivore who wanted to cut down your meat consumption, Cooper, though she isn’t selling herself this way, offers one method, since she shows how a little meat can go a long way.

Not everyone, she says, who visits her popular website, fyf20quid.co.uk, or facebook page, is in love with her low waste approach. “I had a comment on one of my posts the other day saying, ‘Yeah well that’s all right if you want to eat scraps. But I won’t feed my children scraps off the table.’ I thought when did it become a bad thing to not waste stuff? Also, I’m not saying I’m going to take a half-eaten potato off somebody’s plate and use that for something else. I’m talking about food that hasn’t been touched.”

I phone Cooper a few days into my getting into the plan. At this point I’ve made her bircher muesli, tomato base sauce and bacon, cheese and veg hotpot – a kind of cauliflower cheese with a lot of other frozen vegetables and a bit of bacon thrown in. The hotpot was a hit with the kids – Louis, 12 years old, and Max, 10 – though I had to make a section of it without the onions for my youngest. My plan is to go straight into "week five" and do a roast chicken at the weekend, possibly because this feels familiar. We know what it is to roast bird and then made the most of it by boiling up some stock and using the leftovers in a pie. What’s new is the frozen elements, and the new leftovers recipe we are trying in Cooper’s chicken hash.

But, at the same time, I’ve got mixed feelings about the cheap frozen chicken. Since I bought it I’ve been haunted by questions about its welfare – since there was nothing on it saying free-range or organic. “I do say in the book,” says Cooper, “if you can afford to buy organic or free range and that’s what you want to do then do it, but there are people who just can’t afford it. And it’s not that they don’t want to. It’s the same with eggs. Everybody would love to buy straight from the farm free range, but when it comes to a stark choice of either feeding your family or not feeding your family, then tough choices have to be made sometimes.”

It's a reminder of the privilege that is bound up in eating a free-range organic chicken, or many of the foods I eat. She is, she says frequently shocked by what people will spend on food. “People spending £200! I know it’s probably easily done, but it just blows my mind, that one people can afford to that. They must be chucking a lot out, surely? They’re not eating that amount of food?”

As she says it I churn over the fact that I actually have no idea how much I spend on food each week, which probably says a lot about where I’m at. “I think you might be shocked by how much I spend too, then. I mean it’s nothing like £200, but it’s also nothing like £20.” Later, I try to work it out with my husband and we come up with something like £80.

I have to confess that to begin with I’m a reluctant to throw myself fully into the plan– particularly when I start to realise that for the system to work, I have to commit not just to a week, but to her whole 8-week plan. There are things about the plan I struggle with. There is only so much room in my home and this involves a certain amount of bulk buying – though there probably would be space if I threw out all the tins, bags and boxes already in my cupboards. I have an organic veg box delivered and like to get a few things from Weigh To Go, the local plastic-free shop. Though I’m not vegan, I’m trying to cut our family consumption of meat and dairy.

But also an eight week plan sounds slightly terrifying to me. My husband, Andy, and I are the kind of couple that decide things on the hoof, relay-style, calling each other from the supermarket to find out what’s in, or drifting back through Lidl and picking things up last minute, deciding on the day who is cooking. We live within five to ten minutes walk of a Tesco, a Lidl, a Farmfoods and a small Sainsbury and retail foraging is a daily part of our life. Occasionally I splash out on some meat in the farmer’s market. Sometimes Andy, a far better chef than me, batch cooks.

Cooper designed her system during a period on benefits after she had a slipped disc. It’s a book written for families who are genuinely struggling or just about managing – as many in Scotland are. Data produced by the Independent Food Aid Network [IFAN] showed nearly 600,000 food parcels were distributed across Scotland between April 2018 and September 2019, and increase of 22 per cent compared to the previous period, which, the network said was probably just “the tip of the iceberg” of Scots struggling to put food on the table.

But you don’t have to be properly struggling to find something in this book. Wouldn’t most of us like to cut our food bills? Wouldn’t the vast majority of us like to be able, as Cooper puts it, "feed our loved ones good home-cooked food on a budget".

Hers isn’t the only book out there with this message. The cookery book market is awash with guides to how to feed ourselves well for less. Meanwhile newspapers and magazines are also filled with stories about women who have managed to batch cook for their entire family for a week for a stunningly small amount of money. The 2000s may have the era of gastroporn versus clean eating, but it feels as if now we are seeing rise of simplicity, the low budget cook and kitchen frugality. There are countless books around selling to this market from Jack Monroe’s Cooking On A Bootstrap to Miguel Barclay's One Pound Meals series. Most of them are delivering a formula for cooking without pretention, recipes that are all about getting a nutritious meal, cooked from scratch, on the table with minimum fuss. Many of them started out, like Cooper, as bloggers, struggling on a low budget to feed themselves or their families.

Cooper herself has known waves of hard times, which she briefly runs through at the start of the book. “I grew up in Paisley with my mum, dad and big sister,” she writes in her book’s introduction. “Dad was a college lecturer by day and a bricklayer after hours. Mum was the heart of the house. Life was simple and perfect. Then, when I was ten, my mum was diagnosed with breast cancer and died just as I turned eleven.”

Her father remarried 18 months later, and, by the time she had turned fourteen, he had bought a house down the road for her and her 18-year-old sister to live in. The two of them had to quickly start thinking about food and money. “I had to fend for, feed myself and run the house,” she recalls. "My dad used to take us to the local Safeway and we would just go round the supermarket chucking stuff in and it was readymade pies or packets of cheesey pasta, super noodles, the odd ready meal, things that you would just heat up.”

At 16, she met her first husband and soon moved in with him, which was, she recalls, when reality hit. “We were completely broke, on £44 a week in benefit money, and I had to run the house and feed and clothe us on that”. Mostly, what they lived on back then was sausages, eggs and bread. It was only later, when she had her children, that she realised she needed to make nutritious meals.

Five months after she had her first child, she was diagnosed with a heart condition. It was caused by a virus and her heart was double the size it should have been. She was the first person in Scotland to get a biventricular pacemaker. “Those health issues,” she writes in her book, “made me look seriously at how I ate and what cooking really meant. I began to enjoy cooking from scratch”.

Later, she met her current partner, John, through a support group for people who shared her heart condition. Sometime after they had moved in together, she had a slipped disc and had to leave her work, and that was when the financial pressures really started to hit home. “Money got tight,” she says, “and it was at that point I started trying to make it cheaper. That’s when I found out about bulking things out with lentils and porridge oats.”

The recipes are useful because she makes them so easy – but the real virtue of this book is the planner. That, for Cooper, is what it’s all about. “I thought why would I bring out a cookbook? I don’t cook anything different from anybody else. It needs to be about the plan – because that’s what people ask when they first find the page. They go, 'Well, how do you do it?' And unless you actually show them in black and white, they either think you’re lying or you’re eating toast constantly.”

Cooper’s eight-week plan, I start to realise, is adaptable, and not a bad starting place from which to create the kind of diet and cooking regime that suits my aims, time availability, budget and values. One of my worries when I started it was that all my aims for a low carbon, planet-saving diet were going to have to be put on the back burner. But actually cooking the Cooper way has helped me find new ways of doing this. Frugal living is always relatively low impact– it’s often said that those in poverty should be actually having lifestyles that product more emissions, while the very wealthy, or even those on an average household income, cut theirs.

A big principle of her plan is that it’s designed to be very low on waste. Even the fact that she uses frozen vegetables, not fresh, is because “it’s generally cheaper and it’s easier to portion out with less waste”.

According to Zero Waste Scotland, “Scottish households throw away 630,000 tonnes of food waste every year.” Very little of that waste comes from the Cooper house. She even has a recipe for making crisps from potato peelings, and makes sure to use every scrap of the chicken carcass. As she points out, “If you use the whole chicken without wasting any of it, you’re doing your bit. I’ve had people say to me how come you get that many meals out of one chicken and then turn around and say well we just eat the breast and throw the rest away.”

It’s also a plan that makes the meat it uses work hard, so not bad for those looking to wean themselves off a very meat-heavy diet. “When you say you’re bulking meat out,” she says, “people think somehow you’re diluting the goodness. They think you’re just making it cheaper or rubbish. With cottage pie or mince and potatoes, then I use porridge oats because when you fry your mince the oats soak up the juice from the beef and in reality they just taste like beef. You don’t taste them.”

I like Cooper’s way of thinking about things. It’s an acknowledgement that the help that most of us need is not in creating a gastropub style meal, but in making affordable, healthy and enjoyable meals on a daily basis. As I get into the plan, the thing I find it reminds me most of was a time when I tried to follow food writer Joanna Blythman’s exhortation that, given all the things that go into processed foods, we should be cooking from scratch. At the time I found it hard – that it added new time pressures, and even, since I started shunning supermarkets, financial pressures too. In retrospect, I think what I probably needed was this – a proper food planner, a way of looking at cooking that stretches beyond the individual recipe. I needed to think not in terms of meals, but days and weeks.

Feed Your Family For £20 A Week is published by Orion Books

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here