AT a big wooden table in the small untidy kitchen of a raggedy old farmhouse in Lanarkshire, I ask Humphrey Errington what the last few years have been like. It’s been like living in Putin’s Russia, he says. I ask him how he feels about the upcoming court case. The sooner we get in front of a judge the better, he says. And I ask him – because I have to – whether it’s safe to eat the cheese he produces on his farm. It’s as safe as anything else, he says. And he spells it out for me: there is no such thing as zero risk.

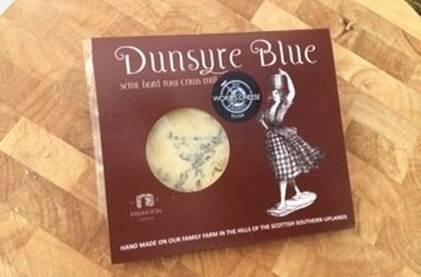

I have to ask the question about safety because of how we got here. In 2016, there was an outbreak of E.coli 0157 in Scotland in which a three-year-old girl from Dunbartonshire died. The food safety authorities concluded the likely cause of the outbreak was Dunsyre Blue, one of the raw milk cheeses Humphrey Errington and his family produce at the farm near Lanark. Mr Errington has always denied the cheese was to blame, but the authorities have stuck to their claim. And later this year one of the 26 people who fell ill in the E.coli outbreak is taking Errington to court for compensation.

What it means is that, finally, the two radically different takes on what happened in 2016 are about to be tested in front of a judge. Mr Errington has already been in court several times before – and has spent about £300,000 (all his life savings) on lawyers. But the cases in the past have focused not on the Dunsyre Blue cheese but on the decision by South Lanarkshire Council to seize other raw milk cheeses made by Errington – Lanark Blue and Corra Linn. The court case later this year, on the other hand, will be the first time a judge has looked at the most important question in all of this: did Dunsyre Blue cause the outbreak in which the child died?

This is what the two sides claim about the situation. In one corner is the law firm Digby Brown which says it is representing a number of people who were diagnosed with E.coli 0157 after coming into contact with Errington products but says it cannot comment further. It’s understood though that it will be suggested in court that 21 of the 26 people confirmed to have the strain of E.coli ate or are believed to have eaten Dunsyre Blue. The case will also suggest the other five could have contracted E.coli from an unidentified person who may have had contact with the cheese.

The E.coli victim that Digby Brown will be representing in court is not willing to be named at this point, but she is prepared to tell me a little about how she is feeling. “When I contracted E.coli I was ill in ways that literally left me scared about what was happening,” she says.

Mr Errington’s take on the situation on the other hand is that he and his family have been consistently and unfairly targeted by the food safety authorities and sitting at that big table in his kitchen he takes me through the last two and a half years in minute detail.

I ask him at one point if he’s a difficult man given how long and hard he has fought this case and he denies it, but it’s obvious he could be a formidable and bloody-minded adversary. Last year, he fought – some might say against huge odds – South Lanarkshire Council’s decision to seize stocks of Lanark Blue and Corra Linn and in the end won £254,000 in compensation from the council. The businessman said at the time he was delighted with the ruling and was focused on getting his business back on track.

He also says he is more than ready for the court case later this year and refutes absolutely that Dunsyre Blue was to blame for the 2016 outbreak. For a start, he says, people simply do not understand the nature of risk with food.

“Every time you put something in your mouth, you’re taking a risk,” he says. “It’s impossible to have zero risk with any food – somebody may have touched it and not washed their hands. And your immune system only exists because you’re ingesting nasty bugs which your immune system learns to cope with. If you live on sterile food, you won’t have an immune system.

"All the records, then and now, indicate that raw milk cheese, when it’s produced under hygienic conditions, is as safe as anything else. There are instances where raw milk, just like meat and everything else, has been associated with illness but in each case if you look at what the reason was, there was a failure in hygiene control.”

Mr Errington says his company has always had excellent hygiene control and adds that he has very specific evidence that will prove Dunsyre Blue was not to blame for the 2016 cases. It was a dreadful shock for him and his family, he says, when Health Protection Scotland and Food Standards Scotland linked the little girl’s death to Errington’s cheese – “for two years they have been very clear that the cheese killed that child” he says – but Mr Errington says that, from the start, he did not believe Dunsyre Blue could be to blame.

“It looked to us very surprising,” he says, “but we consulted experts and said to them ‘do you think the cheese was the culprit?’ and they all came back having looked at it very carefully and said no. So that’s our position.” He also says he has a theory about what the real cause of the 2016 outbreak was but cannot discuss yet it for legal reasons.

As for the next step in this long and complicated saga, that will be defending the case brought by Digby Brown although Mr Errington says he is looking forward to his day in court. “The sooner we can get the thing into court so there can be a proper judicial examination of the evidence the better,” he says. “From our point of view, we want it to come to court.” He says there were people affected by the 2016 outbreak who definitely did not eat Dunsyre Blue.

In the end, Mr Errington hopes the court case might also signal some kind of resolution of what, for him, has been years of struggle over the production and acceptance of raw milk cheese. He would also like to see an end to the stress and strain on him and his family, including his daughter Selina Cairns and her husband Andrew, who run the business day to day.

Standing at the kitchen table, Ms Cairns tells me a little of what it’s been like for her in recent years and the metaphor she chooses is a rail track that she can never get off. She has the business to run, she says, she has her two young children to look after, and she has the piles of legal papers to look over and now there’s the new case looming. “It’s really unpleasant,” she says.

Mr Errington says he has become wearily familiar with this approach from the authorities and says some of the problems go way back almost to the beginning. The farmer and businessman started the cheese-making operation more than 30 years ago with a flock of 30 sheep but says that from the very early stages there was resistance from the scientific establishment who thought raw milk cheese was a bad thing. He also says he and his family have suffered hostile treatment from environmental health officers longing to find something wrong with their cheese. “They were desperate to find something wrong,” he says and adds that it has only got worse in the years that have followed. At times, he says, it's felt like Putin’s Russia.

However, the passion and anger are just as intense on the other side of the case. As well as the upsetting experience of being ill, the E.coli victim who will go to court later this year tells me she’s been unimpressed with Humphrey Errington’s response. “I cannot believe the callousness of that man bleating about his commercial interests while legal proceedings are still ongoing with injured consumers and the bereaved family of the little girl,” she says.

As for Health Protection Scotland, its spokesperson told The Herald it would be inappropriate to comment on the legal case whereas Food Standards Scotland said it had no vendetta against cheese made from unpasteurised milk and that cheese made from raw milk could be safe if produced under the right conditions. However, it also said the decisions taken by the Incident Management Team in relation to the 2016 E.coli outbreak still stood, something which rankles with Mr Errington.

Mr Errington does believe some progress is being made though and is particularly pleased about the result of the court case with South Lanarkshire Council. It cost him a huge amount of money and in the later stages of the process he had to represent himself because he couldn’t afford a lawyer anymore, but he hopes something good may come of it in the end: a change in approach from the authorities.

“The authorities have had to go back into their burrows and think again,” he says. “The great thing is they won’t be able to put us out of business in future by insisting on enforcement regulations which we couldn’t meet.”

Mr Errington hopes the attitude of the general public to risk and products such as raw milk cheese might change too. Made under the right conditions, he says, raw milk cheese is absolutely safe to eat. He talks about his grandmother, who had a farm on Mull, and the Queen (both devotees of raw milk cheese, he says) and admits he was probably influenced by what he sees as their healthy attitude to risk.

“There’s a whole range of products where there’s a theoretical risk of E.coli,” he says. “Strawberries. Smoked salmon. A whole lot of products. E.coli 0157 is a very serious illness – even if you’re a fit young man, you could still be hospital – and some of those who were ill, a large number of those went to hospital. It’s not to be laughed about.” However, Mr Errington says the courts accepted his argument that if a producer controls the cheese-making to the point where the generic E.coli in the milk is below the level of detection, then there is no risk.

Mr Errington also believes our immune systems aren’t as robust as they used to be and that the population as a whole is not eating enough food with good bugs in it.

We go for a short walk round the farm, followed by the family dog, Polly, and as we head down from the house and pass the buildings where the cheese is stored, Mr Errington tells me that his health is very good for a man in his 70s. He worries about the health of the population in general though. We’re far too obsessed with making everything sterile, he says, and perhaps raw milk could help. For years, he says, some people have seen raw milk cheese as a problem. Mr Errington believes it could be part of the solution.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel