It was where thousands of homeless young boys were sent, as well as beggars and orphans. To the massive, former fighting ship, the Mars, moored off Dundee. It arrived on the Tay 150 years ago this month, as Ron McKay reports, anchored forever into the city’s history.

MURDOCH McLeod was just 13 and apprenticed to a firm of bookbinders in Perth. The company was rebinding books from the local library which had been fire damaged when the lad picked up a copy of Swiss Family Robinson and began flicking through it. It would utterly transform his life.

“The foreman allowed me to take it home on a pain of skelping if I did not return it the next day,” he recalls more than a half-century later.

That night, enthralled by the vision of a seemingly limitless world packed full of adventures and japes, McLeod decided to run away to sea.

He was a practical and resourceful boy so, rather than walk the 30 miles to the port of Dundee, he stole a boat in Perth, rowed down the Tay on the ebb tide, stopped short as the tide turned, dined on strawberries from a field, slept in a hay stack and walked into the city in the morning.

There he crept aboard a brig bound for Archangel, hid among coils of rope but was discovered and hauled before the captain, where McLeod told him he wanted to become a sailor and see the world.

“Well, there is a man-o-war just in from Sheerness,” the captain replied, “and they’re looking for boys like you.”

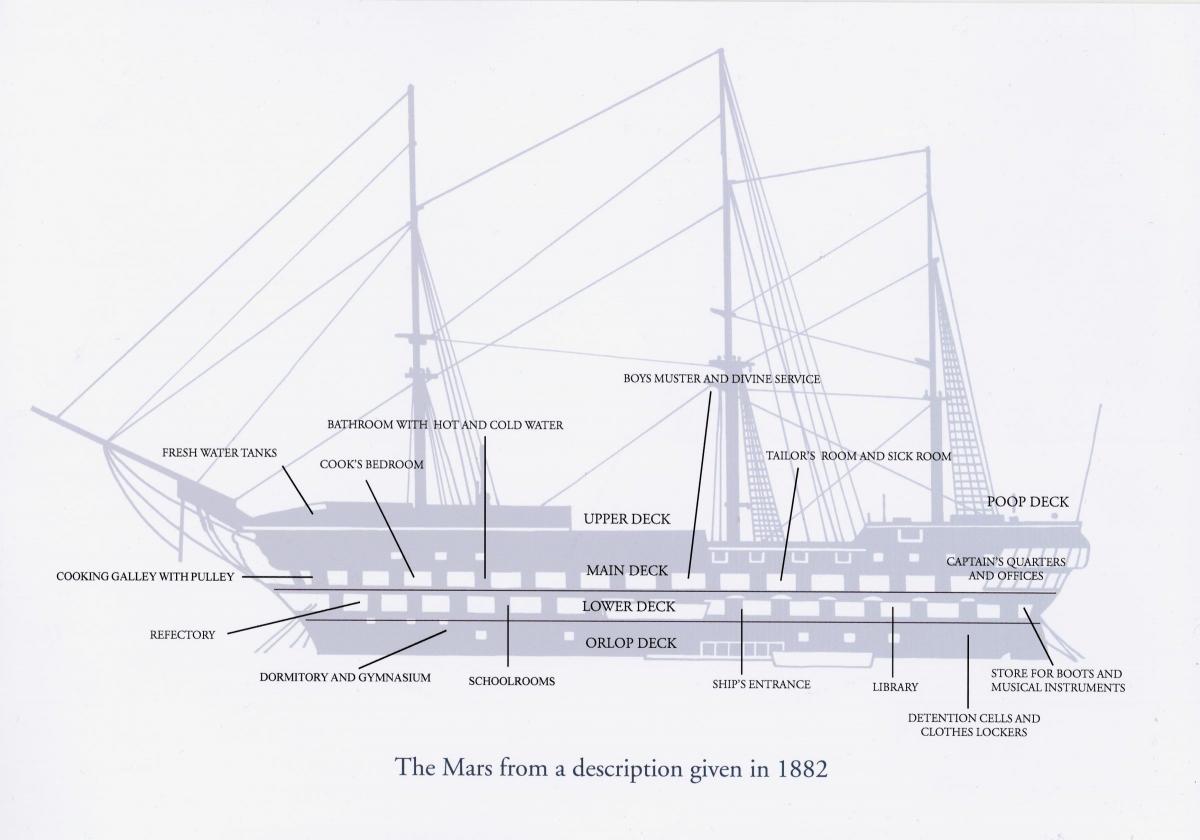

The Mars was a three-masted, wooden sailing ship, 190 feet long, weighing almost 3,000 tonnes, built to accommodate 750 men and 80 guns.

But she had been built across the eclipse of an era. New naval ships were powered by steam and the Mars, although an unsuccessful attempt had been made to install an engine and propeller screws, was redundant, with the Royal Navy planning to scrap her.

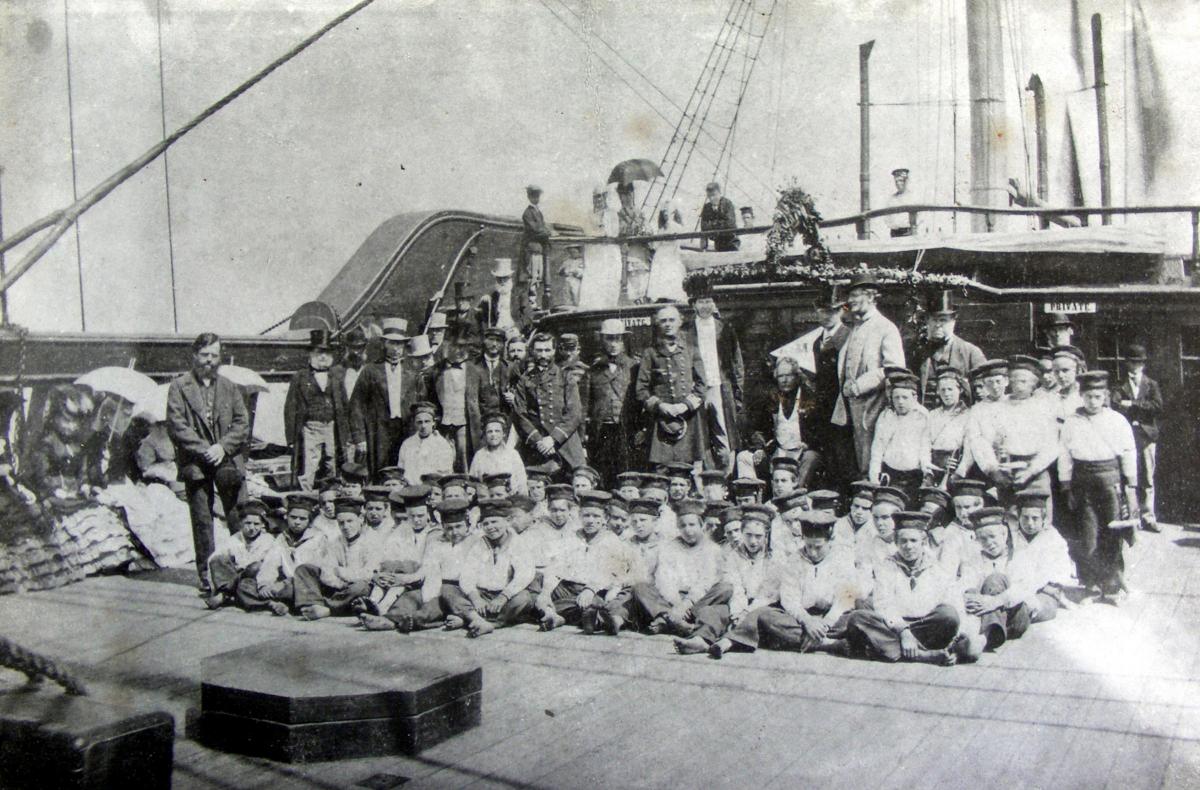

She had been rescued, however, after an initiative by the then Dundee Lord Provost William Hay, and a cast list of the great and good of the city, to use as a floating home and training school for boys up to the age of 16, who would be sent there by magistrates for five years because they were poor, or orphans, beggars or homeless.

Or had fallen in with the wrong crowd, as defined by the authorities. This was as much practical self-interest as charity, getting the problem boys off the streets and out of sight.

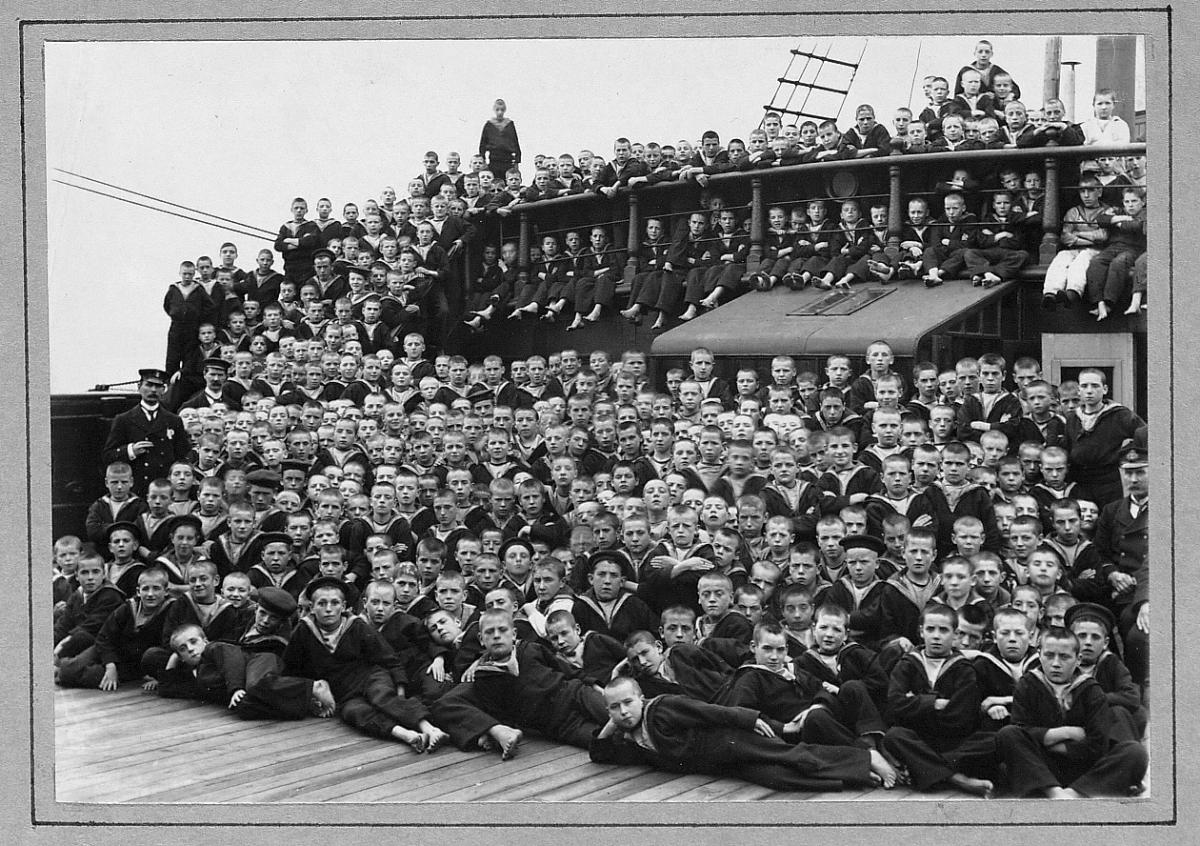

Young Murdoch became not just the first to join the Mars, but the first to enlist voluntarily, unlike the thousands of others who would pass through what was called a training ship but was, for all practical purposes, a reformatory, a prison ship.

In October 1869, as the Mars was arriving on the Tay, Dundee was booming through the textile trade, migrant workers were flowing in and the city was a melting pot of ethnicities and ideas. However, living conditions for the majority were unimaginably primitive and life-endangering.

There was no sanitation and waste was usually tipped into the soil of the unmade streets. There was little or no water supply and what there was came from five polluted wells.

Chloride of lime was spread over the ground as a disinfectant, causing nausea, and infections were rife (more than one in 10 of the population suffered from typhus), overcrowding in rotting hovels was normal and there were up to 300 underground cellars used as homes.

Overlaying all of this was the massive and constant pall of smoke from factory chimneys and houses – there were no smoke abatement measures – and the swelling numbers of people crowding into Dundee.

In 1841, the population was 45,000 – 20 years later it had grown by 30,000 although only 568 houses had been built, and a decade later, in 1871 another 30,000 had arrived, tripling the population to almost 120,000.

Work in the mills was available, but to women overwhelmingly because they cost less than men and were believed to be more nimble-fingered.

Men who stayed at home, if there was one, were referred to as “kettle bilers”. Children roamed the streets, frequently getting into trouble, stealing to stay alive.

These kids were known as “Arabs” (the nickname for Dundee United FC to this day) and although the transportation of children for simple theft had stopped in 1857, kids were still being sent to prison and harsh reformatories.

In 1855, a parliamentary act, applying only to Scotland, allowed magistrates to send kids under 14, found begging or homeless, to an industrial school for five years where, it was hoped, they might get a basic education, learn a trade, or join the military or the navy.

More enlightened magistrates, faced with a young first offender before them, would also send the child to school, rather than give them a record which would last their lifetime.

The move to bring the Mars to the Tay, and become an industrial school, began in March 1869 when the great and good of Dundee met and agreed to press the admiralty for a redundant warship.

This was motivated by self-interest as much as charity, removing beggars and the “Arabs” from the streets.

The Mars was handed over and on the forenoon of August 17, 1869, she arrived at the mouth of Tay, towed by the gunboat Medusa. Hundreds of people came out to watch her arrive.

A contemporary account notes she “is the largest vessel and the noblest in appearance that has ever entered the river Tay ... As she has not been painted for eight years her hull looks anything but smart at present, but the paint brush will soon make a great difference in her appearance”.

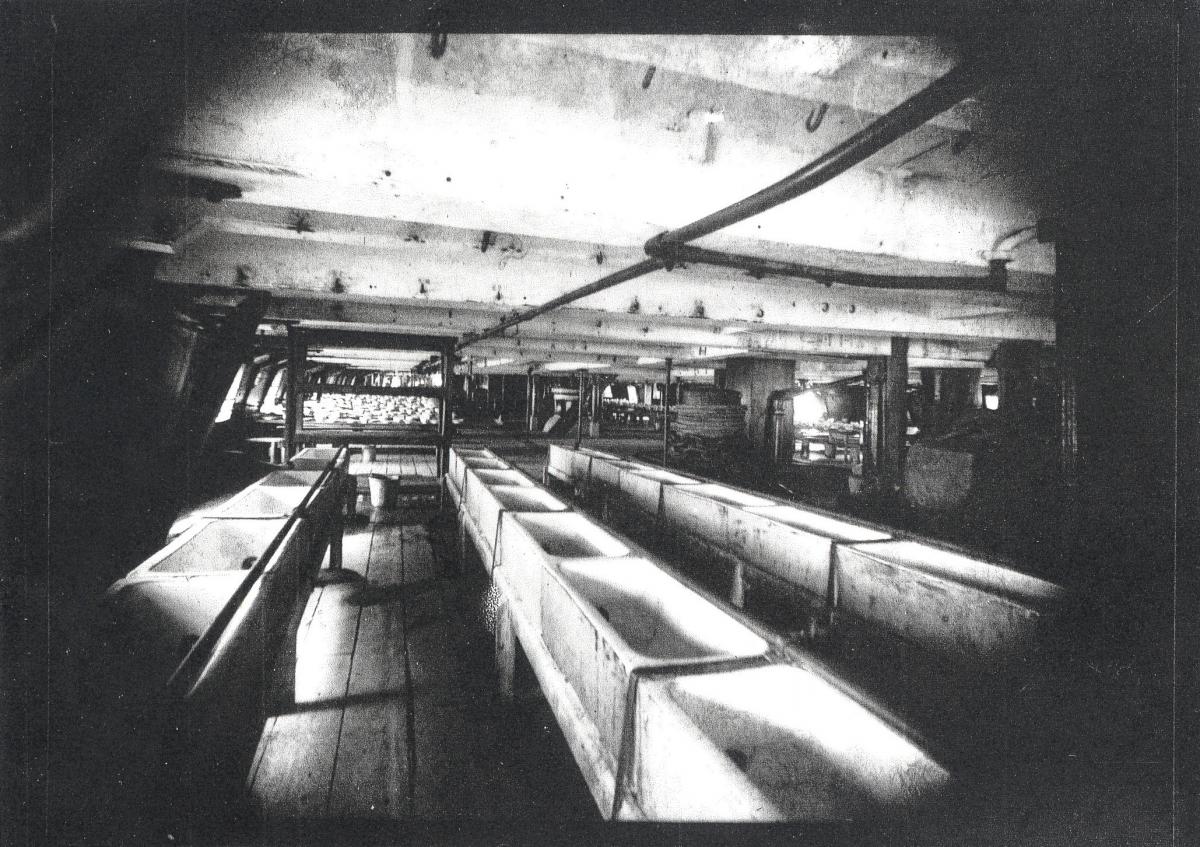

The Mars had four decks, from which all the fittings had been removed. The boys’ accommodation was on the lowest one, the orlop deck, and they slept in hammocks in two rows, with a passage between.

It was bitterly cold and over the first winter ice formed on the Tay.

A number of windows had been cut into the side of the ship for ventilation. “By this arrangement the boys will be prevented from inhaling the impure air which may gather near the roof and be readily observed by the officer as he goes about fulfilling the duties of his watch.”

At the stern were two punishment cells. Discipline on the Mars was strict, modelling naval regulations, where the boys might end up.They wore naval uniform and infractions were harshly punished.

The captain had power to impose solitary confinement, partial stoppage of rations and corporal punishment, but it might not “exceed 18 strokes with a birch or cane, which the Executive Committee, in extreme case, shall have the power to direct to be increased to 24 strokes”.

There were other training ships moored around Scotland but the Mars was the only one to take Catholic boys as well as Protestants and, because of that, it wasn’t just those from Dundee and surrounding areas who were sent there but, increasingly, Catholic boys from Edinburgh and Glasgow.

The regime on board was rigorous. The boys’ days began at 5am with the boatswain’s awakening pipe and the order to turn out. They had five minutes to dress and be standing at the head of their hammock.

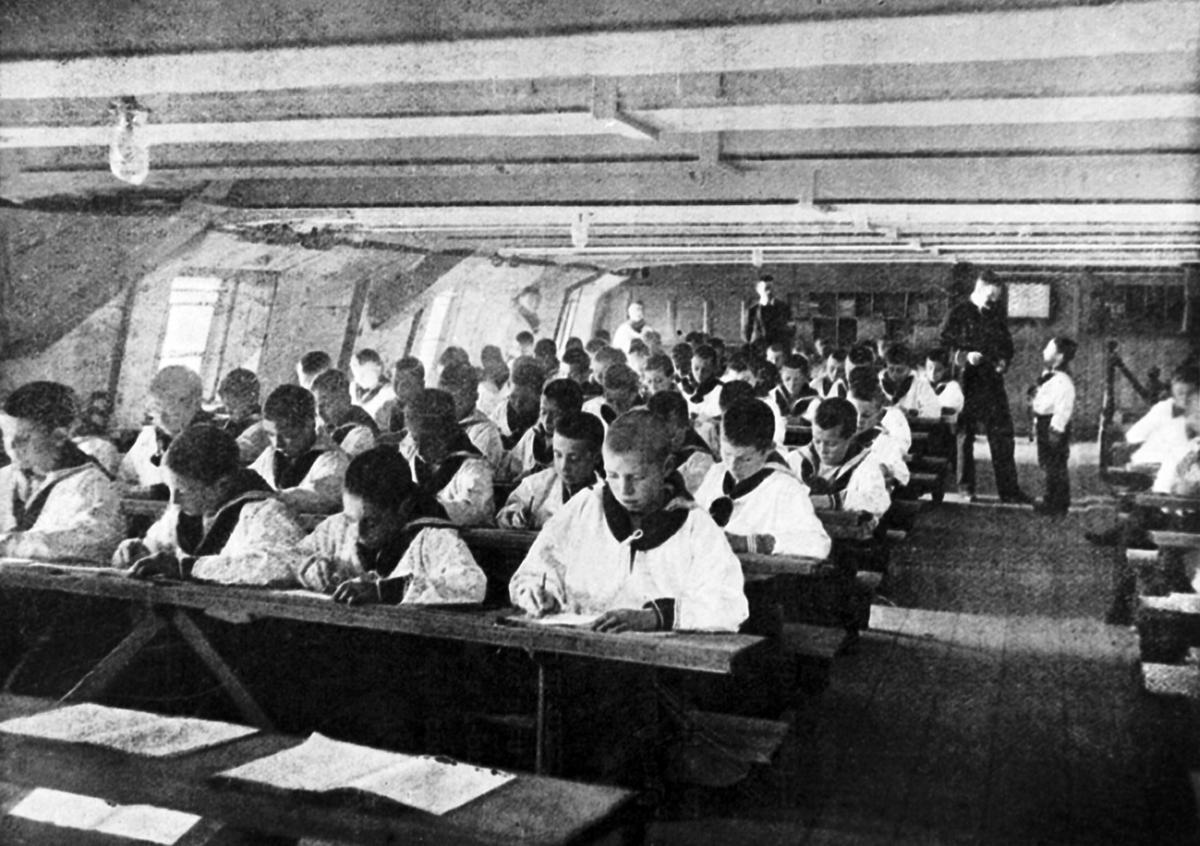

At 5.15am it was prayers, 10 minutes later they were washing the decks, 7am it’s breakfast of porridge and milk, then cleaning up, followed by an inspection (including trousers rolled up above knees) at 9.15am, then schooling in reading, writing and arithmetic for half, while others undertake duties, like painting or splicing ropes.

Dinner is at 12.50 and at 1.30, when it’s over, there’s 45 minutes for recreation. Then the boys who were at school take over the duties of the other watch. Supper – of tea, milk and biscuits – is served at 5.30pm, at 6pm they have three hours for recreation, 9pm it’s prayers and by 9.30 all the boys are in their hammocks.

These kids have also ceased to be individuals. Each has been given a ship’s number, applied to their uniform and other belongings. They are only referred to (and by each other) by their given number.

Some tried to escape, like the very first inductee on the Mars, Murdoch McLeod. He managed to steal a lifebuoy and swam to Newport pier, then walk to Tayport where he was caught by a police constable.

He later claimed the “iron discipline” on the ship involved lashing with a rope’s end.

In July 1871, the foundation stone for the railway bridge across the Tay was laid. The Mars boys were witness to its subsequent construction, just a few hundred yards from the moored ship off Woodhaven, on the south side of the river.

The new bridge was a lattice grid design in cast and wrought iron with a single rail track.

The designer, Thomas Bouch, was given a knighthood on its completion.

It certainly impressed the doggerel poet William McGonagall who composed An Address to the New Tay Bridge.

In 1877, the first engine crossed the bridge, and on its completion in early 1878 it was one of the longest in the world. Former US president Ulysses S Grant, who visited Dundee – and about which Michael Marra wrote a great song – commented that it was a “big bridge for a small city”.

Just over 18 months later, on December 28, 1879, in the middle of a gale, the central span of the bridge collapsed and a train with six carriages, 75 passengers and crew plunged into the Tay. None survived.

Officers on watch on the Mars witnessed the disaster, or its immediate aftermath and they, together with the boys, joined in the search for bodies, a search which became increasingly more desperate, including dropping explosives into the water in an attempt to dislodge bodies (succeeding only in blowing a large Newfoundland terrier out of the water and high into the air). A bounty was put on the recovery of the dead and eventually a large trawl was used which had little more success, snaring just the one body.

The Mars remained on the Tay for 60 years and wove itself into the folklore and heritage of Dundee. Gordon Douglas, a well-known musician, remembers his granny warning him if he was caught misbehaving “We’ll send ye tae the Mars!”.

In 2006, he co-wrote an Edinburgh Fringe musical, The Heart Of Gold, but realised that the history he had based it on he knew little about. Researching it has become an obsession. “Something new comes up all the time,” he says, “I’ve had contacts from family members, stories, from all over the world.”

Douglas lives in Wormit, just a few hundred yards from where the Mars was moored, and he can see the spot on the water from a bedroom window. He has written two books about the ship, as well as the songs, and he has dedicated himself to listing every boy – all 6,562 of them – who stepped aboard the Mars together with their stories.

Many of the Mars graduates went into the forces. Four hundred of them went to the front in the First World War – 70 of them died.

For 60 years the Mars was a local landmark, but the spread of education provision, changes in the law on juvenile crime and the deteriorating condition of the ship marked its end in 1929.

A safety certificate was withdrawn and, on June 27, after six decades, the Mars was towed for what was to be her final voyage to the shipbreaker’s yard in Inverkeithing.

There was resistance, however, from the old ship to the end. So stout were her timbers that three-inch nails bent on them and it took high-explosive to finally destroy her.

We’ll Send Ye Tae The Mars, by Gordon Douglas, is available from Amazon priced at £12.50.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel