THE Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh is 350 years old and since the 17th century it’s been a ground-breaking and sometimes dangerous adventure. Mark Smith speaks to some of the staff who work there – men and women who are discovering, conserving and protecting some of the world’s rarest and most beautiful plants.

Leonie Paterson, archivist

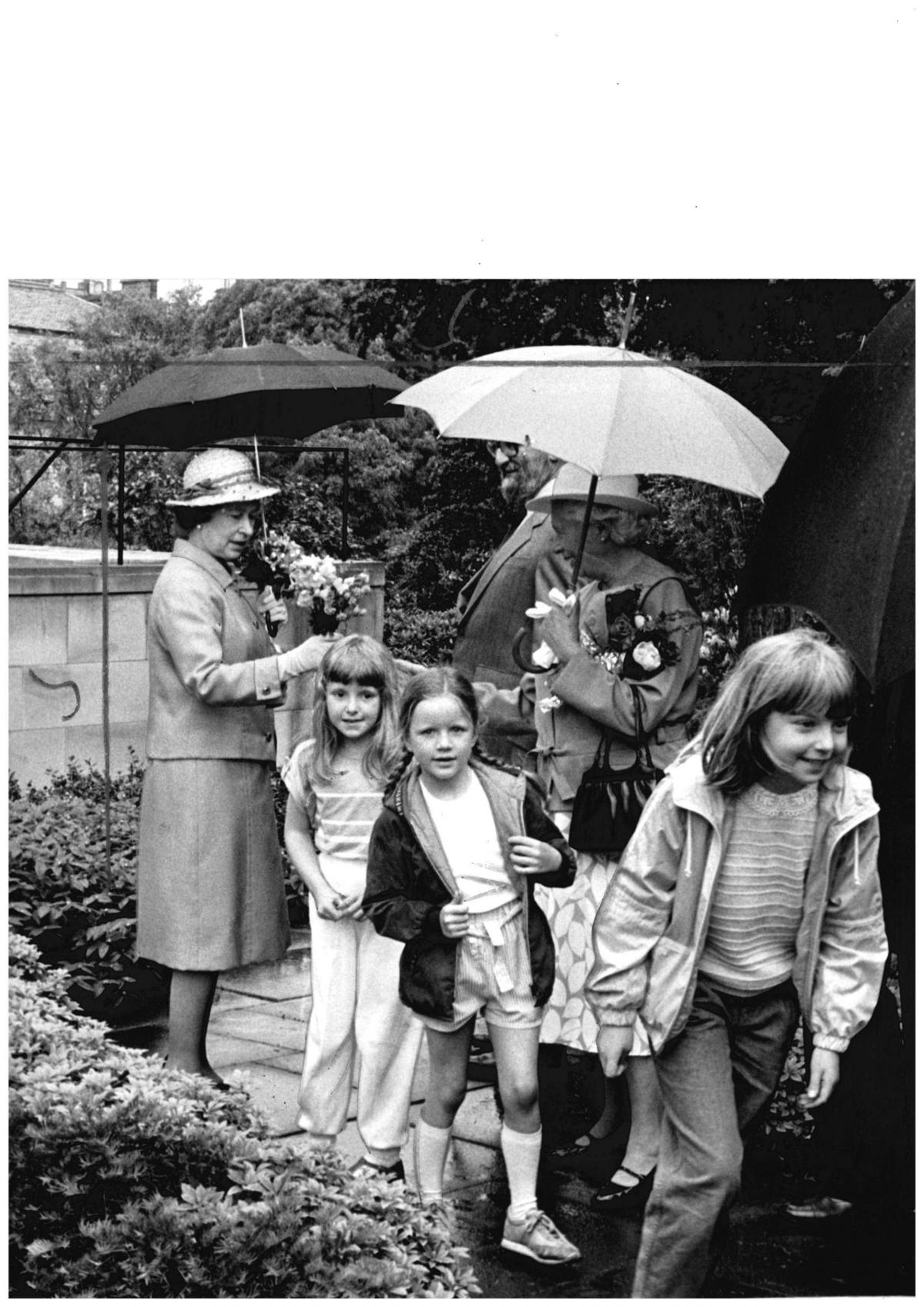

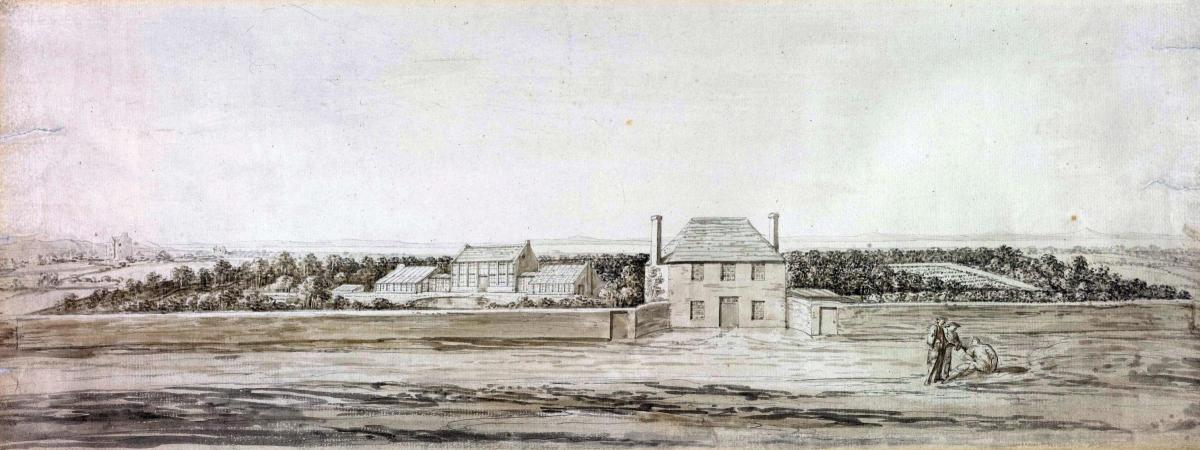

The garden was established in 1670 and the records we have come from the memoirs of our founders, two Scottish doctors called Robert Sibbald and Andrew Balfour. They had seen gardens on the continent where doctors trained in botany and medicine so they rented a piece of land in Edinburgh to do the same here.

The garden would have looked beautiful when it first opened, but it was strictly for the training of doctors and the public weren’t allowed in. I don’t think even now a lot of people realise the research and the science that happens here and what’s been involved in bringing a lot of these plants to the UK – the work of the Scottish botanist George Forrest for example.

Some people have called Forrest the Indiana Jones of botany and he really does deserve that title. He was a plant collector who became associated with the garden in 1903 and went out to China. It was very risky and he could’ve died on numerous occasions.

In 1905 he’d settled just off the Tibet border at a time when a lot of people in that area were quite hostile to Western influences. He heard that there was a plan to besiege his mission and kill everyone so he and two missionaries tried to escape and made their way down the river in pitch darkness on narrow paths – one slip and they would have been dead. They were surrounded and cut off. They had to run for their lives.

Forrest was running towards the river on his own and did a five-hour climb but discovered sentries at the top so had to head back down. They were trying to track him by his footprints so he had to bury his shoes and wade up the river and hide during the day. He spent five or six days doing this but eventually, some locals helped him. Around 31,000 specimens in the Botanic Garden have Forrest’s name on them. We wouldn’t be in the shape we are now if it wasn’t for George Forrest.

I worried when I started here that I knew nothing about plants, but for me it’s been about the people behind the plants and how incredible they were. Charles Austin for example was around at the time of Linnaeus and was horrified at the idea that plants could have sexual parts. But Austin was a great lecturer – once, he self-medicated on coffee when it was unusual and described his blind spots and hallucinations to his students.

I have a great love for the collection of plants. I can look at a plant and say ‘there’s the plant that Forrest named after his wife’ or ‘there’s a plant that someone almost died to get’. My favourite is primula vialii. If you get a whole swathe of them together, it’s the most incredible sight.

Hannah Wilson, Phd student

I grew up in Yorkshire and have always been interested in nature but it was quite haphazard me getting into botany. My undergraduate degree is in mathematics but I finished the course and decided I didn’t want to do maths anymore. I got a summer job in a garden near my parents and got into rhododendrons and ended up working there for four years. I’m now studying for a PHD looking at begonias in New Guinea.

Begonias are a very interesting group to research because they’re so diverse and we have a very good collection here at the Botanics. Later this year, I’ll be going on the Botanics’ 350th anniversary expedition to the central range of mountains in Papua New Guinea. We’ll be starting in the north and heading south and we’ll be ascending 3000m. The idea is that all along the 30-mile route, we will set up base camps and survey the incredible diversity of plants there. We will be camping in the forest and sleeping in hammocks because there’s no flat ground. I’ve never slept in a hammock before!

We are definitely going to find new plants on this trip. New Guinea is still very much under-studied; it’s incredibly diverse. Papua New Guinea makes up only about 0.5 per cent of the global land area but it’s estimated to harbour up to 10 per cent of all global plants, animals and insects. People have always assumed that the flora of Papua New Guinea is safe because it’s so remote and difficult to get to, but there is a global threat from climate change. But the more immediate threat in New Guinea is logging and mining and palm oil plantations.

It’s exciting to be at the Botanic Garden this year and it’s humbling when I remember that I’m a tiny part of such a huge institution. Historically, it’s been a lot about the plants themselves and collecting them and we still do a lot of that, but now I see us moving towards biodiversity loss and the climate crisis.

Martine Borge, conservation horticulturist

I grew up in Norway and went up into the mountains a lot and always felt connected to the vegetation that was all around; it gave me a sense of place. We would pick things to take home and I love working with my hands. I’ve got mud under my nails right now. Some of the sites we work in are difficult to get to but I love that side of the job. Sometimes we have to use drones just to get a look at a plant.

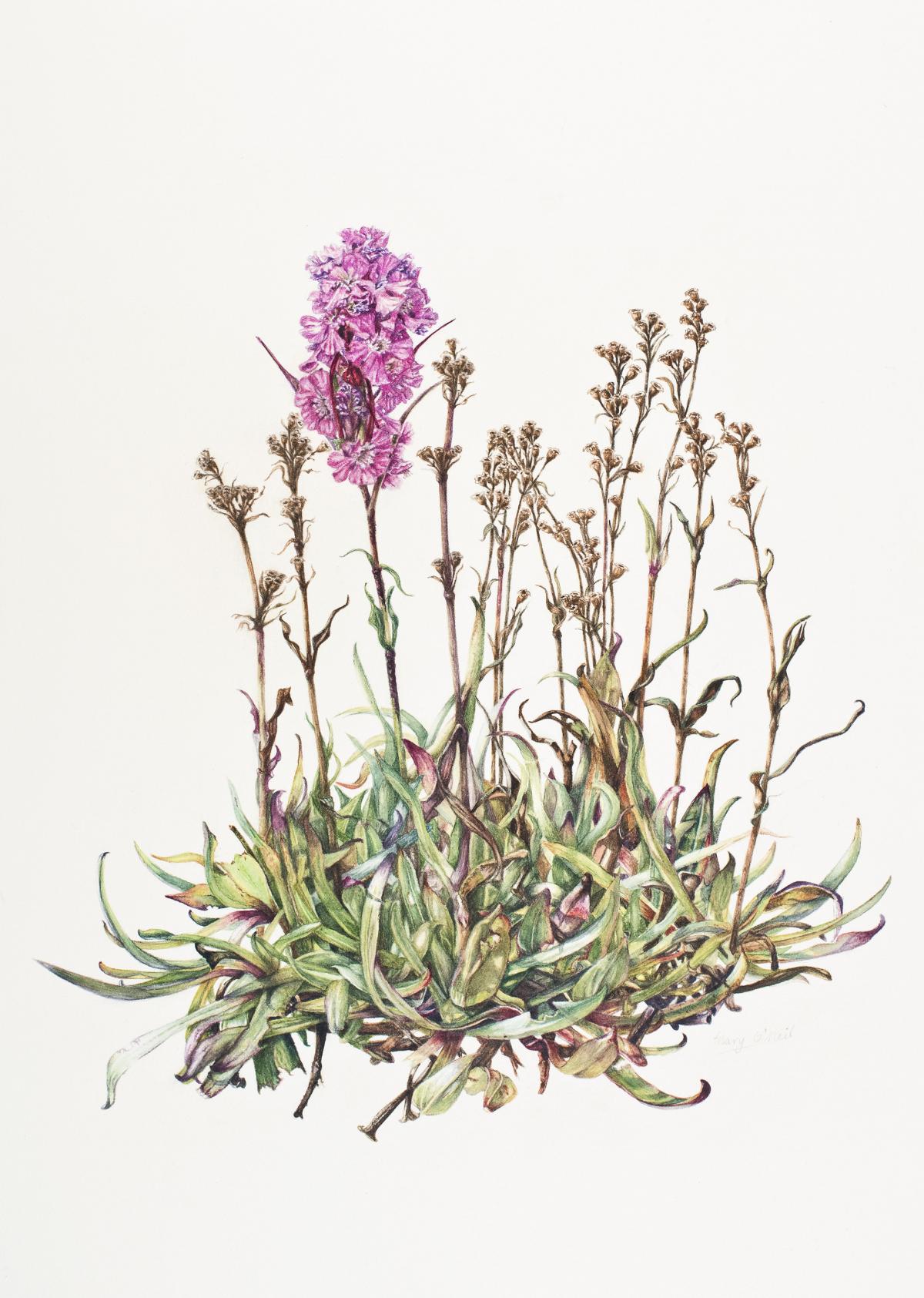

I work on the Scottish Rare Plants project and Scottish rare plants that are threatened. We have 85 per cent of Scotland’s threatened species growing here within the gardens and I look after them; the other side is having some of that material available for reintroduction and bringing the plants back into the wild to try to establish more healthy populations. Getting things re-established can be a challenge – all the threat may still be present and we are facing climate change as well.

One of our big projects is with a plant called alpine blue sow thistle which is only growing in four sites in the Cairngorms. It’s on the brink and all the sites are tiny little ledges where it’s safe from grazing from sheep and deer. It’s a big problem for most threatened plants in Scotland. We collect material and it’s grown here and we’ve been able to cross-pollinate between different populations. It can be sad to see them clinging to ledges but we have five new sites for the thistle. You feel very attached to the plants you work with – they are so charismatic and having a connection to plants is good for your general wellbeing.

I am worried about where we are in Scotland – we have a lot of beautiful wild looking spaces but actually a lot of those spaces are grazed and you can see that they are very bare and botanically quite poor. We need links between populations and habitats and a reduction in the number of deer.

The Botanics mean so much to me and I feel proud to work here. We’re very much ahead of the curve on conservation. We have so much to learn from plants – they are making use of renewable resources all the time and doing their thing. A big thing is not taking plants for granted; some of them have uses that they haven’t even worked out.

David Knott, curator of the living collections

I was born in Edinburgh and actually learned to walk in the Botanics. My grandfather was an old-style pharmacist and grew a lot of plants in his garden; my parents weren’t terribly keen on gardening so it skipped a generation. I came to the Botanics as a student of horticulture over 40 years ago. If you have a passion for plants, the Botanics is one of the finest plant collections in Scotland if not the world. We have 100,000 plants over four gardens.

In our gardens, there’s definitely been a shift to more ecological planting. We have a Chilean hillside at Benmore, a Tasmanian forest at Logan, Nepalese planting at Dawyck and here in Edinburgh we have a Chinese hillside. Growing plants that are endangered is an increasing part of what we do – understanding the threats as well. We want to explain and conserve for a better future.

One of my favourite plants is the Scottish primrose which grows up on the Sutherland coast. The emotional connection to plants was brought home to me when we had the storm of 2012 when we lost a number of substantial trees in each of our gardens. What was interesting to see were the emotions of regular visitors to the garden. They were horrified to see the extent of the damage and the support we got surprised me – I could see how much people enjoy and respect the gardens.

Recovering from the storm is a process of replanting but the timelines are very different from human timelines – you’re planting not just for one or two generations but five or six. When we lose trees, it’s sad but it’s obviously an opportunity to replant as well.

The effect of climate change in the gardens is something we’ve been aware of for 10-15 years. In the last ten years, we’ve had our windiest, coldest and warmest weather. We’ve just installed a rain garden to mitigate some of the impacts of climate change – the aim is to capture and reduce the run-off.

Gardeners are by their very nature optimistic. Losing a tree in a storm or a plant to a disease leaves a gap and an opportunity. We have to garden more sustainably so we mitigate some of the impacts of climate change. It’s about going back to the basics that our parents or grandparents were using.

Dr Mark Hughes, researcher

I am from Cumbria originally and worked in industry for years before I quit and went to university to do botany and I’ve now been working on begonias for 20 years. My interest started when I was an undergraduate and was the botanist on an expedition to Ecuador and spent a lot of time looking for begonias. I became fascinated by them.

What fascinates me most is the massive diversity – it’s the fastest growing group in terms of the species that are being discovered. On average, across the world, we’re discovering between 50 and 100 new species every year. Some of them have very tiny distributions, they might grow on one rock and nowhere else. It’s important we carry on doing this work to ensure all these rare plants have a voice and recognition – if they haven’t got a name, they can be ignored – a fundamental first step to getting protection for biodiversity is making sure they have a name. It grows and it has a voice.

What we’re trying to do is stop extinctions by bringing things in to cultivation – we can give plants an official threat status at various levels from least concern to critically endangered. We can discover something only for it to go straight on the threatened list, which happens quite a lot.

Sometimes it’s heart-breaking. I’ve been to parts of Borneo for example to parts of the country which are meant to be protected and there’s not a tree left standing. You can feel powerless; it’s a mixture of coal mining and palm oil. It would be easy to feel overwhelmed, but if I can just save a handful of things, that is still worthwhile. It’s important not to get despondent because there are still people doing really great work. There is a gradual awakening and people feel they have more of a responsibility – we have to translate that into some kind of action.

We are still in a golden age of discovery – it’s estimated that globally the biggest flora of the world is the undiscovered flora and I can go into a forest and think ‘what the hell is that? That is totally new’.

There’s probably about 70,000 species still to be discovered. As for begonias, because there are nearly 2000 species, we’re kind of running out of names because you can’t use the same name twice so we have to get quite creative; quite often I name them after people who’ve been associated with collecting them. There is a begonia named after me – begonia hughesii. It’s lovely. I’ll leave a bit of a legacy.

The Botanics has stood the test of time because it has always modernised. We depend on our archive and our past but we’re never the same. We are focusing far, far more on conservation - we are realising the value of applying what we’re doing more directly to conservation and that will be part of our new strategy for the future.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here