Kitted Out: Style and Youth Culture in the Second World War explores the style, uniform and identity of young people in wartime Britain, the United States and occupied Europe. Here the author Caroline Young shares her favourite stories

May Lamont, Lumberjill, Women's Land Army

Like many young women, May Lamont believed it was unpatriotic not to wear make-up and perfume, even when working outdoors as a lumberjill for the Women's Land Army. The eldest of eight children and with a lorry driver father, she was born in 1925 in Glasgow. May, who left school at 14, saw how her mother struggled with so many children and knew as a teenager she didn't want to be in that position.

In 1943 she saw an advert in the Glasgow Herald looking for girls to work with the Forestry Commission, based in Edinburgh – a job which didn't need parental permission or a birth certificate, which she didn't have. In front of the interview panel, she announced that she wanted to join because "I come from a big family and I want to go out into the world", and that she knew a little about horses because her grandmother had one for her fruit barrow. Ecstatic at the news she was accepted into the Timber Corps, she took the train from Queen Street Station to Mucherach Lodge in Dulnain Bridge.

May only carried with her a small suitcase with just a few belongings, and she couldn't help but notice that two girls from Edinburgh who were sharing her room in the lodge opened their suitcases and unpacked their nightwear, underwear, towels and a toilet bag – something May had never come across before. Before running away from home, May had woken early to pinch three pairs of her sisters' knickers and two vests from the pulley, but hadn't managed to bring a towel.

Embarrassed at their lack of possessions, May and another girl from Glasgow held back from unpacking their cases until the Edinburgh girls had left the room. She was soon issued with her uniform for the Timber Corps, providing her with a supply of clean new clothing. 'We had khaki corduroy trousers, 2 green sweaters, 2 cream shirts, a beret, 4 pairs of socks and brown brogues and a greatcoat,' she recalled. While her uniform was too big for her, she pulled up the straps, and showcasing her own individual style, tied a scarf around her head with a fashionable flare.

When her group of lumberjills moved to the area of Black Mount, Bridge of Orchy, she found that her social life also took off. The Special Air Service (SAS) and the Highland Light Infantry were stationed nearby, and they would hold raucous dances. The Canadians stationed nearby would also send trucks to collect the girls and take them to dances in Scout halls.

"The Canadians were rubbish dancers, good at throwing you about but for individual dances, waltzes and foxtrots you needed a Scotsman," she said. "Always records, Glenn Miller, Mantovani, the Foxtrot was my favourite dance. In the biggest hall of all, the one at Crianlarich, I won a Miss Lovely Legs competition!"

The Fighter Boys of the RAF

Richard Hillary, who found fame for his wartime memoir, The Last Enemy, signed up to the RAF Volunteer Reserves with his Oxford university friends in the summer of 1939. After completing RAF training at Kinloss in May 1940, and then posted to Montrose as part of 603 Squadron, they relished the attention they would receive from their pilot's wings now sewn onto their tunics.

He and his friends Peter Pease, Peter Howes and Colin Pinckney in 1940 called themselves the 'long-haired boys' and they enjoyed appearing "slightly scruffy" in upmarket restaurants, shocking the "pink and white cheeked young men" of the infantry regiments. This carefree, irresponsible attitude would be put to the test during the Battle of Britain, where the stress and trauma on these young men was masked by hard drinking and black humour.

The RAF Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR), introduced in 1936, opened up flying to the lower-middle classes too. These auxiliary squadrons had a reputation as "weekend flyers", and the public in the 1930s was shocked by their rebelliousness. They drank heavily, drove fast sports cars and recklessly performed aerial stunts. In the summer of 1939, Tony Bartley trained at No. 13 Flying School in Drem, East Lothian. He and his friends bought a sailboat they named Pimms No. 4, he went into Edinburgh every Saturday for "drink safaris", flew right under the Forth Road Bridge for a dare and 'fell madly in love with the Lord Provost's daughter'.

As well as being nicknamed the "Glamour Boys" for the way they wore their uniform with desirable panache, the pilots of Fighter Command were also called the "Brylcreem Boys", because of their movie-star hairstyles, and left the top button of their uniform tunic undone, which became known as "Fighter Boy style".

Winston Churchill coined the nickname "The Few" for the men of the RAF who pushed back the Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain. They were, as Tony Bartley wrote, "a generation born to war, as a generation earlier our fathers were. Some of us were men, but most still boys … we were fit and fearless, in the beginning. By the end, we were old and tired, and knew what fear was. We expected to die, but, in the meantime were determined to live every minute of each day. Aeroplanes were our first love, followed by girls and alcohol. All three were indispensable to our existence."

According to Bartley, to cope with the unrelenting wave of Luftwaffe and the loss of their friends, they needed 'the alcoholic tranquiliser and stimulant in order to keep going, all the time'. Bartley recalled parties in the mess at RAF Hornchurch in May 1940, when Spitfire pilot Bob Holland knocked back his Benzedrine with whisky and hammered out frantic music on the piano.

Sometimes the hero worship didn't sit easily with them. When Bartley was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC), he went to his tailor to have it sewn on, but it was a mark on his uniform that he felt uneasy about. "I felt supremely conscious of the blue and purple striped decoration under my wings. As I made my way to my parked car, pedestrians looked, stopped and then smiled. A young girl stranger ran up and kissed me. The public wanted to shake our hands, touch us, idolise us."

Mary Morris, QA

Irish nurse Mary Morris, whose diaries recorded her time in the Queen Alexandra's Royal Army Nursing Corps (QAs) in London and overseas, observed how the RAF were "a special kind of people, outwardly talking in cliches and using their own 'in' language."

She added: "The RAF are the heroes of today, but too much is expected of them. The pilots have their mugs hanging above the bar, and if somebody fails to return from a mission, the mug remains there, but his name is never mentioned, not even by his closest friends. They are a strangely superstitious bunch of boys, many just down from Oxford. The 'few' are now becoming fewer so we must hope that Jerry eases up for a while. They are all so brave and so desperately tired."

Mary Morris was accepted into the QAs in 1944, and was incredibly proud of the uniform she could order from Austin Reed. She wrote, "It is very attractive – a simple grey dress – scarlet cape and white organdie headdress – two lovely shining pips on the shoulder and our own QA badge."

By the time preparations for the D-Day invasion were taking place, she found that wearing her new uniform brought respect and authority. "There were troops and armoured vehicles everywhere and I was amused to see how quickly the wolf whistle was transformed into a smart salute when the soldiers noted our two pips!"

Boarding ships to be taken to Normandy for the invasion, Mary and her fellow QAs were instructed to be fully kitted out in battledress, tin hats and Mae West life jackets, which she said "would increase our girth and make the effort of climbing down the scrambling net very difficult. It might have been easier if we were all eight months pregnant."

Mary Morris was stationed in a ward at the front line in Normandy where she treated international patients from all sides, including Canadians, Poles, Free French soldiers, Americans and Germans. "This multi-national microcosm of a Europe at war is interesting and sad. A badly wounded Cockney says 'thanks, mate' to Hans as he gives him his tea and fixes his pillows. Why are they all tolerant of each other inside this canvas tent, and killing each other outside?"

Elizabeth Richardson, American Red Cross

As a member of the American Red Cross, Elizabeth Richardson was stationed in England and France in 1944 and 1945 as a "Clubmobiler", serving up coffee and doughnuts to troops going to and from combat. The Clubmobile was a service club on wheels, fitted with coffee and doughnut equipment, as well as carrying chewing gum, cigarettes, magazines and newspapers, and a Victrola record player and speakers to blast out the latest records. Three glamorous American Red Cross women worked from each van and were taken to a location close to American forces bases by a British driver.

In 1943 there were almost 500 American girls working for the American Red Cross, supported by more than 6,000 British volunteers. Always offering a cheery welcome and conversation, they were dressed in a blue wool skirt and jacket with Red Cross insignia, or when near a conflict zone in France, they wore a military-style uniform of boots, belted shirt and calottes, jacket and cap. It was hard work lifting the coffee urns and deep-frying the doughnuts in the van, with the smell permeating their hair, but they always tried to keep up their appearances with lipstick and a smile.

Liz was tall, athletic and striking looking, and she liked perfume and makeup, going to dances, and speaking fondly of home with American soldiers. The girls had all been selected by the Red Cross for their ability to banter, to have the right All-American look, to be hip to popular culture and to know the latest slang and music.

For many GIs in England, meeting an American woman was a rare treat. Liz wrote home soon after she had arrived: You feel sort of like a museum piece – "Hey, look, fellows! A real, live American girl!" and that "If you have a club foot, buck teeth, crossed eyes, and a cleft palette, you can still be Miss Popularity". The main thing is that you're female and speak English. These women stayed in the minds of the homesick GIs they had flirted with.

Liz wrote to her parents from France in spring 1945, that she was passing some resting troops in France when she heard them shout, "Hey Liz! Hey, Milwaukee!" she said. "It was a whole unit that we had known in England and we had a wonderful reunion right there on the road. And yesterday I met one of the cooks who had helped us brew our coffee during that week of the invasion of Holland. It's funny how they remember you and stranger yet how we can remember them after seeing thousands and thousands of faces."

At Le Havre airport on the morning of 25 July 1945, Liz jumped into a two-seat military plane to fly to Paris. Near Rouen the plane crashed. Liz and the pilot were killed instantly. She was 27 years old.

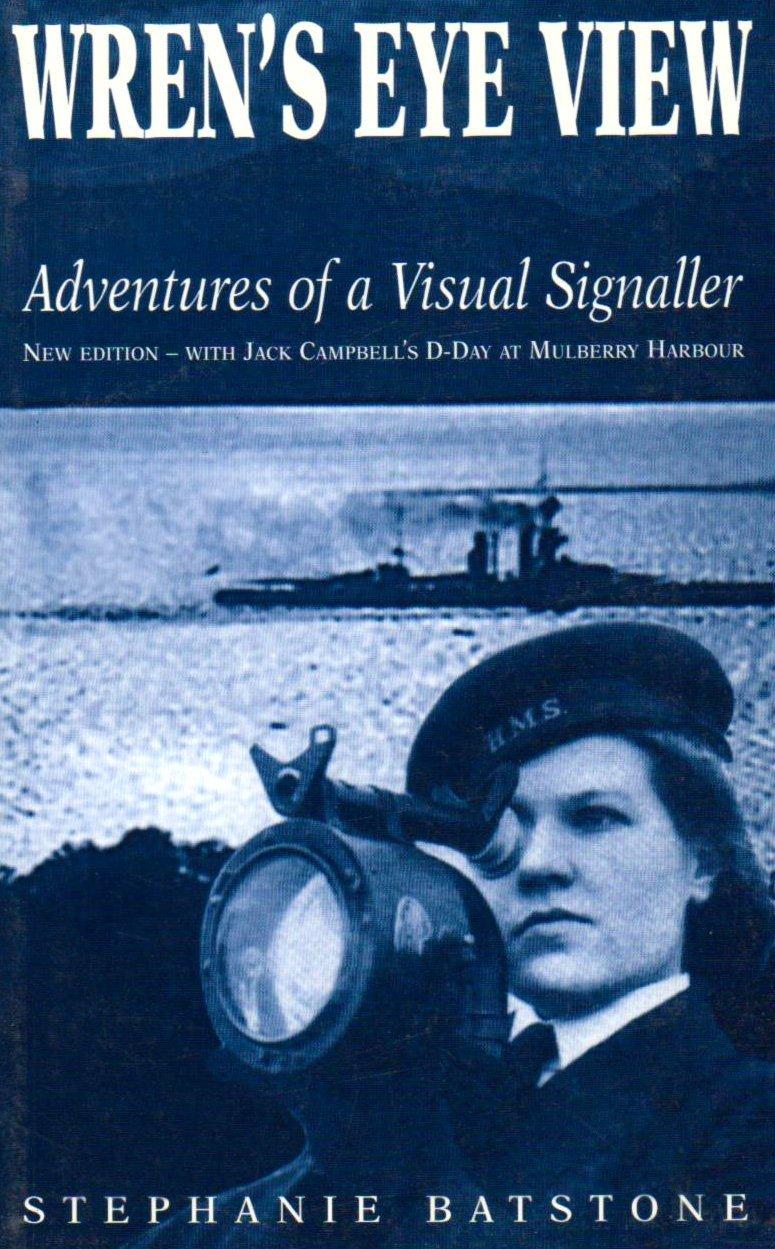

Stephanie Batstone, WREN

Stephanie Batstone always dreamed of going to sea. She had looked admiringly at the poster for the Wrens, with a clear goal that she would one day wear the smart navy uniform. "I had nothing against the ATS or the WAAF except that they didn't have telescopes and generally lacked the special glamour of the Navy," she wrote.

When Stephanie came across a leaflet appealing for recruits to train as visual signallers, she jumped at the chance. "As soon as I saw the photographs of girls signalling with lamps and doing semaphore and hoisting flags up masts, I knew that was what I was going to do."

As a new recruit at HMS Cabbala, she wrote of her excitement at finally receiving her full uniform, for "now we should look like the girl on the poster". They queued up to be presented with a pile of clothing, which included two skirts and two jackets, two pairs of black lisle stockings; two pairs of shoes, a raincoat, a greatcoat, six shirts and a hat, a pair of bell bottoms.

The bellbottoms had been the item of clothing Stephanie had most wanted to get her hands on, as they "were our badge of office, our passport to a man's job, and in them we intended to swank around the camps and bases of the future with our bottoms cheekily outlined and our waists nipped in". However, reality proved a bit different. Stephanie's bellbottoms were just sailor's trousers, "enormous thick things, all padded with lumps of wadding, hundreds of buttons, blue and white stripe linings and enormous let-down flap on the stomach".

While they had hoped to be posted to Portsmouth, the centre of action for the Wrens, Stephanie and her friend Dorothy were drafted to Oban in October 1943. Ganavan War Signal Station was a mile out of town and up a steep hill, and they trudged through wind and rain to reach it, with their wellington boots and raincoats not enough to keep themselves dry. The signal room had an iron cylindrical stove, which they used to dry their constantly damp clothing, and "after a few weeks our bellbottoms had a circular burn mark round each thigh where we had leaned over the stove and scorched them on the top rim".

When they got a call that they were to be inspected by the signal officer, they realised they had fallen some way below the image of the ideal Wren: "I had on a pre-war school sweater with frayed cuffs which had unsuccessfully been dyed navy from yellow, over a shrunk white pullover in which my father had once gone on a boat in 1912. My bellbottoms were shapeless and stained with coffee, and my toes were sticking through a pair of ancient plimsolls."

Kitted Out: Style and Youth Culture in the Second World War by Caroline Young is published by History Press, priced £18.99

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here